Island of Lost Souls

It's become a bit of a fashion to bash Martin Scorsese, and that's understandable--in his films of the '70s (Mean Streets (1973), Taxi Driver (1976) he was an exciting independent filmmaker who hurled his personal obsessions on the big screen; a breathtaking experience and, many of us thought, an essential one. The achievement wasn't so much the violence, which can be bloody, or the immediacy of style, which can be a head-rush thrill, but the self-confessional quality of his cinema, the sense that he's flashing us images of his soul. If we at all respond (and there are those that don't--that are in fact repelled by Scorsese's candor), his achievement becomes all the more extraordinary.

How do you top work like that? Scorsese tried; in Raging Bull (1980) he attempted to dissect the psychology of a violence-obsessed brute accursed with a thirst for redemption (come to think of it, Scorsese might have been prophesying the rise of Mel Gibson). In The King of Comedy (1982) he documented the queasy relationship between a battle-fatigued celebrity and his psychopath fan (think of it as Taxi Driver meets Network). In The Last Temptation of Christ (1989)--easily my favorite of his '80s work--he brought immediacy and angst to the ossified story of Jesus Christ (possibly the film's most iconic image for me was Judas half-dragging Jesus past a broken brick wall--Christ, on the mean streets of Jerusalem). This decade was a searching, a restlessness, a reaching out to various genres, time periods, subject matter; often the attempt and approach, the process by which he tried to explore chosen material, was at least as interesting as the end result.

In the '90s there was still some stretching (The Age of Innocence (1993) was an adaptation of Edith Wharton; Kundun (1997) his adaptation of the Dalai Lama's autobiography), but in key films you saw a concerted effort to pull back, to consolidate over familiar ground. Goodfellas (1990) returned to the genre he is best known for, the Mafia film--it became his most acclaimed picture since Raging Bull. Casino, made some five years later, is to my mind the more interesting work, taking actors from the previous production (Joe Pesci, Robert de Niro) and a similar milieu (the Mafia, this time operating in Vegas) and pitching it at the level and magnitude of opera.

This past decade is possibly his most problematic--he has become Martin Scorsese, America's most respected commercial filmmaker and a cinematic institution; he is able to raise a budget and set of expectations few other filmmaker can handle. Some say he can't--that he's fallen from grace, sold out, whored himself to Hollywood for thirty pieces of silver (or the modern Babylon's equivalent, in thousands of dollars). There's something to that argument--his budgets have become larger, he has come to tackle more conventional material, and the results are more decidedly mixed.

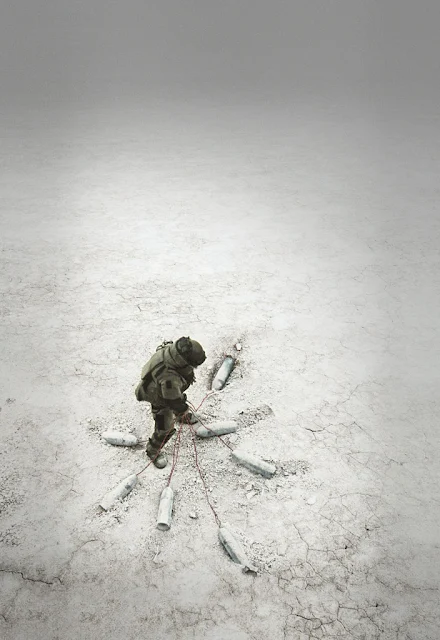

I think it's the mixed results that should clue us in to what he's doing--or at least trying to do. Gangs of New York is the Hollywood historical epic brought to seething life in the sets of Cinecitta; more than the plot (a simplistic one of a boy avenging his father), what possibly interested Scorsese was animating Herbert Asbury's nonfiction history, and juxtaposing the struggle of tiny human figures against the background of a city rising, as it were, from primordial mud (you saw that mud in most scenes, plus the wood four-by-fours sprouting like the citizens' mute aspirations out of the sodden earth). The Aviator (2004) was Scorsese's take on the Hollywood biopic; Hughes' life here not only paralleled the lives of contemporary power figures (a post-election George W. Bush, for one) but climaxed with an introverted life-death struggle: Hughes shutting himself in a room, to deal with his inner demons. The Departed (2006) is perhaps Scorsese's most conventional work--ironically it won him the long-coveted Academy Award for best director--but Scorsese manages to recast Andrew Lau and Alan Mak's thriller as an evolutionary struggle between two rival tribes (their tribal leaders, past breeding age, are identified as the source of both authority and corruption), the final shot revealing who is in the best position to eventually inherit the earth.

Scorsese's latest, Shutter Island (2010), an adaptation of Dennis Lahane's novel

(2010), an adaptation of Dennis Lahane's novel

and, presumably, his take on the Hollywood psychological thriller, is both his least conventional and for many most problematic. The plot is ridiculous, the acting and atmosphere, overwrought. Easy enough to say this is deliberate, that Scorsese intentionally brought the film's emotional tone up to fever pitch, the better to say what he's trying to say--but what is he trying to say? It's difficult to pin down the theme of a Scorsese film; when he's at his best it's well nigh impossible. The best you can say--as with Goodfellas or Mean Streets or a Gangs of New York--is that he's aiming for an immersive experience, that he wants to fill you with the sights and sounds and emotions of a specific cultural milieu.

and, presumably, his take on the Hollywood psychological thriller, is both his least conventional and for many most problematic. The plot is ridiculous, the acting and atmosphere, overwrought. Easy enough to say this is deliberate, that Scorsese intentionally brought the film's emotional tone up to fever pitch, the better to say what he's trying to say--but what is he trying to say? It's difficult to pin down the theme of a Scorsese film; when he's at his best it's well nigh impossible. The best you can say--as with Goodfellas or Mean Streets or a Gangs of New York--is that he's aiming for an immersive experience, that he wants to fill you with the sights and sounds and emotions of a specific cultural milieu.

This film alludes to Dachau, to abuses at mental institutions, to the Cold War and mind control experiments; the film also pays homage to, among others, Sam Fuller's Shock Corridor and Val Lewton's haunting mood pieces (I think it a disservice to call them 'horror films'). Critics complain that he's tossing out red herrings, he's referring to other films like a film geek (funny, Quentin Tarantino refers to other films in his latest movie, and not as many people pay mind). Perhaps they've lost patience with Scorsese; perhaps they feel that what he's doing has become tiresome, stale. I understand the sentiment.

This film alludes to Dachau, to abuses at mental institutions, to the Cold War and mind control experiments; the film also pays homage to, among others, Sam Fuller's Shock Corridor and Val Lewton's haunting mood pieces (I think it a disservice to call them 'horror films'). Critics complain that he's tossing out red herrings, he's referring to other films like a film geek (funny, Quentin Tarantino refers to other films in his latest movie, and not as many people pay mind). Perhaps they've lost patience with Scorsese; perhaps they feel that what he's doing has become tiresome, stale. I understand the sentiment.

Is the reasoning “at least he's directing” so disingenuous? I see him as taking one Hollywood genre after another, and undermining them by tossing out the plot, leaving in the conventions (at least most of them), and telling the story (and we know how little regard he gives story) his way--through the rush of imagery and music, like Michael Powell on amphetamines (and perhaps a few hallucinogens). Perhaps, and this I think is the most serious charge, he has moved away from the sources in his life that made his work such a charged experience--that feeling of stepping into a confessional to listen in every time we step into a movie theater with his name on the marquee. Possibly the well has run dry, and he's had to move on, taking up mainstream Hollywood as the source (monetary, anyway) of his inspiration. Perhaps all he has left is his ability, his skill at telling stories visually--is that such a little thing?

Of his later films, or at least of his visual style when doing the later features (I'm not even going to comment on his documentaries, which I think are tremendous, and a whole other ball of wax) the key film, I think, isn't any particular feature but an omnibus, the 1989 New York Stories, for which he directed the segment “Life Lessons,” an adaptation of Dostoevsky's The Gambler. The key moment there, the single crucial image with which Scorsese possibly identifies the most (still does, for all I know) is of Soho artist Lionel Dobie (Nick Nolte) standing before a huge canvas, poised and breathless, as if about to dive in. His love life's a wreck, his woman has nothing but contempt for him, he's under pressure to deliver for an upcoming gallery show, he possibly suspects he's lost his soul (I know Scorsese constantly worries about this, and on the evidence of his recent work most critics must be wondering as well), he possibly hopes to regain it through work, and he's about to try--swiftly and spectacularly, in a symphony of flashing brushes, smearing fingers, spattering paint. Not an easy place to be, but I think it's the place Scorsese most wants to be, even if he has nothing to say, even if he has no one to say it to.

First published in Businessworld, 4.15.10

.jpg)