Sex and the silly

And the Von Trier Flying Circus continues on its merry rounds, this time with Mr. Von Trier taking on one of his favorite subjects: self-humiliation.

Oh, you thought I was going to say 'sex?' Hah--I wish. More on that later.

Nymphomaniac: Vol. 1 is the first half of a four-hour work, this part devoted to setting up the framework: badly beaten Joe (Charlotte Gainsbourg) is picked up by Good Samaritan Seligman (Stellan Skarsgaard), who for his kindness is allowed to listen to her raunchy adventures as a nubile youth (played with vampiric intensity by Stacey Martin). Along the way Seligman compares Joe's seduction techniques to fly fishing, her true love Jerome (Shia LaBeouf) to a cantus firmus in the polyphonic symphony of her life; along the way Joe beds hordes of men, at one point giving us an extensive picture catalog of all the penises--long or short, dark or pale, circumcised or foreskinned--that have penetrated her, fore and aft and sideways, throughout her sexual career.

The tone is somewhere between a Victorian erotic novel and a Ron Jeremy porn flick, a mix of the dreamily sensual and vulgarly direct (that description may not be 100% accurate--a genuine Victorian novel would have considerably more whipping (Vol. 2, maybe?)). The fable told by a sensual protagonist goes back at least as far as De Sade's Justine or his masterpiece 120 Days of Sodom, and right there you see a difference: De Sade's narrator in the former is a youthful innocent in the process of being corrupted, in the latter are hedonists attempting to corrupt a herd of youthful innocents. Joe's a wanderer of sorts but her travels and eventual transformation generate very little friction; she basically slides into her groove with remarkably little drama and even less fuss (well, a brief discussion of the Fibonacci numbers 3 and 5), riding to town on an endless series of Toms, Dicks and Harrys with nary a tube of Vaseline in sight (just a quick lick of the fingers, applied to the right orifice).

It's amazing how fast this gets old, without the frisson of guilt or the concept of sin; when she confesses to having secreted lubricating fluids at the moment of a major character's death, Seligman promptly lectures her on the naturalness of the phenomenon. When she's confronted with one consequence of her actions--a visit from her lovers' wife (a dizzyingly distraught Uma Thurman) and family--the moment should be a chance for some emotional traction, only the dialogue is so laughably bad ("would it be all right if I show the children the whoring bed?"). Thurman plays the wife as a combination of sarcastic civility and barely checked rage, and the mix--as in most Von Trier movies--doesn't quite gel, doesn't quite sound like the words of an angry spouse trying to get some of her own back.

It's a consistent problem with Von Trier. He wants to provoke, but fails to do the necessary research to cause actual damage (Dogville should have been a powerful condemnation of the United States' puritanical hypocrisy only it becomes clear after sitting through the first hour that the director has never even set foot in the country); he wants to move us, but can't take the time and effort to escalate his heroines' suffering convincingly (in Breaking the Waves he jump-cuts from innocent Bess propositioning other men for sex to innocent Bess being stoned by children for propositioning other men for sex, without giving the town gossips enough time to do their work properly (do the kids have some kind of Sixth Sense for adultery?)).

Sometimes Von Trier commits both sins simultaneously--refusing to do the research and take the time and effort, in this case to properly chronicle Selma's downward spiral in Dancer in the Dark (the legal circumstances through which she forces her own conviction being so hilariously unlikely you have to be high on drugs to refrain from laughing, much less find her guilty).

Sometimes he's so caught up in the mechanics of his emotional effects--in Melancholia the exact shape and progression of his protagonists' depression, clearly meant to represent his own--that he takes for granted the world's literal end, a cataclysm which looks less like the actual astronomical event and more like its digitally enhanced Disney version, bright and colorful and easy to digest. Makes you want to ask: why bother ending the world if it's going to look so slapdash? Almost bad enough to drive one to melancholia.

Course I'm not 100% sure; haven't seen Vol. 2 yet. For all I know Von Trier recovers and turns this ponderous Skin Odyssey into a masterpiece. He's done it before, transformed an irritating turd into an emotionally shattering work of art (i.e. The Idiots, where the final scene either redeems the film or is the only redeeming moment in the film--can't quite decide which, and the fact that I can't is a source of much of its fascination). Based on his track record though and based on the trajectory this picture is presently taking--wouldn't hold my breath.

Next week: Nymphomaniac: Vol. 2

First published in Businessworld, 8.22.14

Friday, August 29, 2014

Thursday, August 28, 2014

Secretary (Steven Shainberg, 2002)

Posting this 2004 article partly because I refer to it in an upcoming piece about a Now-on-DVD erotic film, and because well erotic films need no excuse, really.

Different strokes

Steven Shainberg's Secretary, an adaptation of a short story by Mary Gaitskill, turns on a nice little premise: Lee Holloway, a neurotic young woman fresh out of the mental hospital (Maggie Gyllenhaal), comes home to her alcoholic, physically abusive father and battered mother. When things get rough, when Lee's mother gets knocked around a little or Lee feels especially depressed or frustrated, she hides in her bedroom where she has squirreled away (like a stash of dope) a sewing kit full of sharp instruments, one of her favorites being the lovely ceramic figure of a ballerina whose toes are sharpened to a point; with the smoothness that comes from long practice, she draws a bright line down her well-scarred upper thigh.

Later she lands the position of secretary to E. Edward Grey (James Spader), a control-freak lawyer seated in a vast office. Grey likes perfect spelling in all his correspondence and perfect professionalism in all his staff (mostly Lee, and a paralegal who seems to pop in once in a blue moon); he likes to vigorously redline Lee's typing mistakes with a thick marker and, at one point--when the mistake seemed particularly minor--likes to order Lee to bend over his desk reading her faulty letter while he smacks her buttocks with an open palm. Masochistic employee meets sadistic employer in isolated office environment: ingredients, apparently, for the perfect relationship.

It's a fantasy, of course; nowadays American businesses don't call their staff "secretaries," they call them "assistants;" "assistants" don't use manual typewriters and liquid paper (except maybe in public libraries, and even there it's a dying art) they use word processors and spell-check programs. Shainberg presents a fairly strange world--a Dario Argento torture chamber as conceived by Disney's production designers--presumably in the hope that the soft-focus would make this (mildly) twisted version of a romantic comedy easier to take.

That's basically my problem with the picture--that it's a tale of perverse love told wholesomely. The action isn't hardcore; it's barely softcore, just brief sessions of spanking, a few uncomfortable postures, maybe one or two glimpses of hardware. There's even this suggestion that what they're doing is therapeutic and ultimately helpful to Lee's self-image and sense of worth--as if S&M needed an uplifting message to make it more acceptable, a lifestyle choice like colonic irrigation or the Atkins diet. Lee's character is at rock-bottom, what with her history of mental instability and her troubled family--being tied down can only be a step up; Grey is so thoroughly entombed in his King Tutankhamen suite that punishing Lee is a breath of fresh air, a chance at cardio exercise. It's so laughable a sell--kinky sex for squares--that you end up believing none of it.

If anything saves the picture it's the performances. Spader in White Palace and sex, lies and videotape and even Wolf (as rival to Jack Nicholson's semi-human monster) has always projected an intriguing presence, a yuppie yumminess with just a hint of corruption; his smoothly confident lawyer has a genuine relish for inflicting pain and (beyond that) just the faintest suggestion of guilt at relishing such pain. Gyllenhaal, all saucer-eyes and naughty-girl smile, is even more crucial--on her slender shoulders stands the picture's credibility, and she sells it better than it deserves. She conveys her earlier loneliness with directness and simplicity; when she discovers the pleasures of corporal punishment her wide-eyed sense of discovery is genuinely arousing, preventing you from laughing at all the awkward positions (in a picture that requires such delicate balance a chuckle is appropriate, a guffaw devastating).

Shainberg employs the kind of glossiness required for conventional erotic fantasy; he even has a visual and rhythmic crispness that suggests wit. Secretary is enjoyable for what it is: a fairly fresh twist on a tired genre, so tired even something halfway decent looks special.

When it comes to authentic S&M, though--well, there's American porn, preferably classic '70s (Japanese "pinku" is even better); there's Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ which, much as I loathe it artistically, does show an obsessive spirit. There's Jang Sun-Woo's Lies, which sketches a convincing portrait of an S&M relationship in the process of self-destructing (especially like the oddball humor--the lovers, for instance, scrounging through junk for pieces of wood to beat each other's behinds with).

Even us supposedly staid, sexually repressed Filipinos have done better work: Laurice Guillen and Raquel Villavicencio's Init sa Magdamag (Midnight Passion, 1983) is about a woman who changes persona with each man she beds, most memorably a semipsychotic sadist (I'd go so far as say it's my favorite of a limited and disreputable genre).

So: Passion for the hardcore crowd; Lies for the truthseekers; Init for the artistically imaginative. Secretary I'd say is strictly for the beginning masochist, something soft and tender and ultimately bland. Different strokes, folks. Different strokes.

First published in Businessworld, 9/24/04

Steven Shainberg's Secretary, an adaptation of a short story by Mary Gaitskill, turns on a nice little premise: Lee Holloway, a neurotic young woman fresh out of the mental hospital (Maggie Gyllenhaal), comes home to her alcoholic, physically abusive father and battered mother. When things get rough, when Lee's mother gets knocked around a little or Lee feels especially depressed or frustrated, she hides in her bedroom where she has squirreled away (like a stash of dope) a sewing kit full of sharp instruments, one of her favorites being the lovely ceramic figure of a ballerina whose toes are sharpened to a point; with the smoothness that comes from long practice, she draws a bright line down her well-scarred upper thigh.

Later she lands the position of secretary to E. Edward Grey (James Spader), a control-freak lawyer seated in a vast office. Grey likes perfect spelling in all his correspondence and perfect professionalism in all his staff (mostly Lee, and a paralegal who seems to pop in once in a blue moon); he likes to vigorously redline Lee's typing mistakes with a thick marker and, at one point--when the mistake seemed particularly minor--likes to order Lee to bend over his desk reading her faulty letter while he smacks her buttocks with an open palm. Masochistic employee meets sadistic employer in isolated office environment: ingredients, apparently, for the perfect relationship.

It's a fantasy, of course; nowadays American businesses don't call their staff "secretaries," they call them "assistants;" "assistants" don't use manual typewriters and liquid paper (except maybe in public libraries, and even there it's a dying art) they use word processors and spell-check programs. Shainberg presents a fairly strange world--a Dario Argento torture chamber as conceived by Disney's production designers--presumably in the hope that the soft-focus would make this (mildly) twisted version of a romantic comedy easier to take.

That's basically my problem with the picture--that it's a tale of perverse love told wholesomely. The action isn't hardcore; it's barely softcore, just brief sessions of spanking, a few uncomfortable postures, maybe one or two glimpses of hardware. There's even this suggestion that what they're doing is therapeutic and ultimately helpful to Lee's self-image and sense of worth--as if S&M needed an uplifting message to make it more acceptable, a lifestyle choice like colonic irrigation or the Atkins diet. Lee's character is at rock-bottom, what with her history of mental instability and her troubled family--being tied down can only be a step up; Grey is so thoroughly entombed in his King Tutankhamen suite that punishing Lee is a breath of fresh air, a chance at cardio exercise. It's so laughable a sell--kinky sex for squares--that you end up believing none of it.

If anything saves the picture it's the performances. Spader in White Palace and sex, lies and videotape and even Wolf (as rival to Jack Nicholson's semi-human monster) has always projected an intriguing presence, a yuppie yumminess with just a hint of corruption; his smoothly confident lawyer has a genuine relish for inflicting pain and (beyond that) just the faintest suggestion of guilt at relishing such pain. Gyllenhaal, all saucer-eyes and naughty-girl smile, is even more crucial--on her slender shoulders stands the picture's credibility, and she sells it better than it deserves. She conveys her earlier loneliness with directness and simplicity; when she discovers the pleasures of corporal punishment her wide-eyed sense of discovery is genuinely arousing, preventing you from laughing at all the awkward positions (in a picture that requires such delicate balance a chuckle is appropriate, a guffaw devastating).

Shainberg employs the kind of glossiness required for conventional erotic fantasy; he even has a visual and rhythmic crispness that suggests wit. Secretary is enjoyable for what it is: a fairly fresh twist on a tired genre, so tired even something halfway decent looks special.

When it comes to authentic S&M, though--well, there's American porn, preferably classic '70s (Japanese "pinku" is even better); there's Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ which, much as I loathe it artistically, does show an obsessive spirit. There's Jang Sun-Woo's Lies, which sketches a convincing portrait of an S&M relationship in the process of self-destructing (especially like the oddball humor--the lovers, for instance, scrounging through junk for pieces of wood to beat each other's behinds with).

Even us supposedly staid, sexually repressed Filipinos have done better work: Laurice Guillen and Raquel Villavicencio's Init sa Magdamag (Midnight Passion, 1983) is about a woman who changes persona with each man she beds, most memorably a semipsychotic sadist (I'd go so far as say it's my favorite of a limited and disreputable genre).

So: Passion for the hardcore crowd; Lies for the truthseekers; Init for the artistically imaginative. Secretary I'd say is strictly for the beginning masochist, something soft and tender and ultimately bland. Different strokes, folks. Different strokes.

First published in Businessworld, 9/24/04

Tuesday, August 19, 2014

A Most Wanted Man (Anton Corbijn, 2014) - a belated tribute to Philip Seymour Hoffman (1967 - 2014)

In belated tribute to Philip Seymour Hoffman (1967 - 2014)

In belated tribute to Philip Seymour Hoffman (1967 - 2014) Hamburg's most wanted

Reading Le Carre it's striking to see how much value he puts into stillness and silence. His most dramatic scenes take place in the most muted of places, where noise is not only not present, but unwelcome (I'm thinking of Smiley holding a handful of strings in the climax of Tinker, Tailor, Soldier Spy, Alec Leamas being led away in The Spy Who Came in From the Cold and then realizing what's going on). Silence for the Le Carre operative is a useful weapon--it draws out the target in an interrogation, forces him to fill the vacuum with noise of his own (hopefully valuable intelligence), deflects notice or attention from others in such a way as to leave the agent free to do what needs doing. More, silence is the mark of the thinking man, the intelligent man. You can easily believe Le Carre's hero (anti-hero, whatever) will slip past Bond or Bourne while they ponder the best way to beat information out of their victim, then vanish before either flatfoot evens ha a clue.

Enter Gunther Bachmann, played with an almost Mandarin sense of mystery by the late Philip Seymour Hoffman. Bachmann was a big deal once; he operated networks in Beirut which, thanks to American interference, were exposed and destroyed; now he's haunting the streets of Hamburg, picking up detritus here, there, linking one bit of information to another in a series of daisy chains that--hopefully, hopefully--will lead to some significant target. Someday.

Have not read Le Carre's novel; hear from some critics that it's somewhat strident in its protests towards the United States' policy of extraordinary rendition, with its portrait of rude crude American intelligence agents, its story of a one-time torture victim (based loosely on the experiences of Murnat Kurnaz) seeking asylum in the West. Anton Corbijn's adaptation of A Most Wanted Man is in my book anything but: like his previous The American, it's less a story than a study, not of the refugee but of the gruff unshaven German espionage agent tailing him, trying to suss out the young man's role in the city's uneasy geopolitics (Le Carre's boorish Americans have been distilled into the far more ambiguous figure of agent Martha Sullivan, played with sinister silkiness by Robin Wright).

George Clooney in The American was pretty much the whole show; here it's Hoffman, and good as Clooney was (an introverted knot of tension in an otherwise obscure film, with a rather cliche shootout for a climax) Hoffman holds you in a ruthless grip. He slouches, splashes whiskey in his coffee, smokes an endless chain of cigarettes (you could believe he'll die of cancer long before an assassin's bullet) and in a German-accented growl, declare that he's doing all this "to make the world a safer place." Corbijn keeps the camera not exactly zoomed in on him--Hoffman's constantly caught in long or medium shot, the director doesn't seem to believe much in closeups--but aware of him somehow, pointing him out as the dilapidated corner in an otherwise aseptically clean German city.

And it wouldn't work--would be another American, imploding with its own inwardness--if it wasn't for Le Carre's crackerjack script. Fitting in detail after patiently acquired detail, Bachmann constructs a compelling picture: of wealthy Abdullah, possibly contributing to a charity secretly channeling funds to terrorist networks. As with Le Carre's best spies Bachmann plays the long game--prefers the barely-seen objective over the more immediate goal--and the author works the same way, saving the revelations for last, increasing tension incrementally with every turn of the screw. Quite an achievement, I think, that the film's best thrill involves a man with a pen hovering over a sheet of paper, trying to decide whether or not to sign.

What follows--the capture, the quick flurry of guns and agents and shrieking vehicles--is almost anticlimactic. Bachmann seems aware of this too: he's most alive when staring at a video of the target pacing her cell, or peering past a crowd at the man haunting a street corner. The hunt is all, he seems to be saying (in the book is "Bachmann's Cantata," a long and angry summation of contemporary geopolitical history which Corbijn (wisely, I think) leaves out; Hoffman's Bachmann as opposed to Le Carre's is almost inarticulate in his secretiveness); all else is denouement, disappointment, despair.

A powerful conclusion, but Corbijn arrives at it the way Bachmann--the way Le Carre himself--does: by patient accumulation of detail, by understatement and subtle contrast. Like his collaborators Corbijn plays the long game, his gaze fixed on the distant objective somewhere in a barely-glimpsed future.

Monday, August 18, 2014

Lucy (Luc Besson), Under the Skin (Jonathan Glazer)

You got some 'splainin to do

You don't know the thrill the surname 'Besson' sends up my spine--that is till I realize the crucial 'r' is missing.

Without said letter I know I'll get something--a step up from Michael Bay, not quite Paul W. S. Anderson, the French equivalent of a Philly 'steak wit and Whiz: not haute cuisine, but a fairly tasty handful of kitchen grease.

So it goes with Lucy. The movie's all about awakening human potential in the mind, usually pegged at ten or fifteen percent, and what happens when we reach the upper nineties and beyond--a possibility that any neurologist will tell you is total fantasy; we do use 100% of our brains, only not all at once, or all the time (Mythbusters spent an episode with an MEG machine demonstrating this). Surprised Morgan Freeman lent his name to this enterprise, after hosting all those science shows on TV--afraid he's lost some scientific street cred with me.

So--thoroughly silly adventure based on totally false premise; what's left? Besson used to have style--in The Last Battle, or La Femme Nikita or Leon or even as late as The Fifth Element he showed some ability to stage and shoot an action sequence (just don't expect him to come up with plausible characters, or reasonably affecting drama). He works best with a huge dose of humor, with one character--almost always male--standing in for the director and often providing the ordinary schmo's POV, layered with fairly witty commentary (Jean Reno in Leon; Bruce Willis in The Fifth Element).

Oh, and the rocket launchers. Besson has got to have his rocket launchers--I think it's in his contract. Only time he had to do without far as I know was in The Messenger, and only possibly because he couldn't work them into a script set in 15th century France (he made do with catapults, lots of 'em).

Digital effects have rendered him lazy, I think. Used to be his action had pop, a kind of violent grace that depended on actual human agility and daring, instead of said agility (not to mention flames and shrapnel) being digitally added post-production. I watch Leon and La Femme Nikita with a kind of guilty giddy delight; the action here inspires no guilt or gid, only unmitigated contempt. And maybe more than a little discomfort at the rather virulent racist stereotypes on display, of sinister or rapacious Asian gangsters (to be fair Choi Min-sik--Park Chan Wook's favorite actor, far as I know--puts some grunt and savor to his role as Korean mob boss, for some unexplained reason operating in Taiwan).

In the end the victim (Scarlett Johansson--goofy at first, then increasingly less interesting) attains transcendence, but of a kind so digitally and emotionally uninspired you want to blank out and disappear as well. Besson's intentions are more than noble--he seems to admonish us, amidst the gasoline flames and mayhem, to rise above ourselves, to seize this moment in our short lives and live life fully. The man should listen to his own words; he seems to be bouncing after the next step in cinematic evolution with impotent awkwardness, flapping helplessly at his goal on little dodo wings.

Now Johannsson in Jonathan Glazer's Under the Skin starts out the way she ends in Lucy, as a blank-faced nonhuman. Only in Under it's the start of a Kubrickian take on the vampire film, Glazer's best-effort attempt to adapt an unadaptable novel by Michel Faber (which I haven't read, for the record).

The first half is really the better part; after an opening involving planetary alignments a la 2001 (sequence ending with a closeup of an eyeball that could as easily be Dullea's), the film follows a young woman's predatory practices as she lures men one by one into various apartments and houses, to end up in an eerie reflective pool (a dimensional door, I'm guessing, leading to the home planet of whatever intelligence is directing the lure). Unpleasant events follow, though they aren't half as unsettling as the cool distant manner in which Glazer witnesses them--with only the slightest of musical accompaniments (more a collection of sound effects really) and almost nary a close-up, Glazer adopts the uninvolved, unfeeling point of view of the alien intelligences he depicts. He has Johansson smiling and asking various menfolk to step in her van, and the friendly warmth with which she does this--the casual yet efficient way she immediately establishes that this or that passenger is friendless and unattached--is chilling. She's prolific and relentless, yet never quite so obvious that she alarms her targets (on the other hand most of them are so intent in getting in her pants it's like a running gag--she can't herd them in fast enough).

This distant tone is most successful--and most horrifying--in one particular scene, where the lure (don't feel right calling her an actual 'woman') visits a beach and starts talking to a tourist camping out in a tent. He interrupts their talk to rush to the water and rescue a couple in peril from the oncoming waves. She walks to the water past the couple's child shrieking in the sand, and the point hits home: this figure with the gorgeous lips and come-hither sway isn't human. She can successfully imitate form and manner to the point of seducing practically anyone with balls but it's all clearly a mask, to assume or drop at any moment, at her convenience.

Later she develops a conscience, the film a more conventional narrative, and some of the chill is lost--for the better or not is debatable (don't think so, myself). The ending (skip the rest of this paragraph if you plan to see the film!) feels forced--would a man intending to assault an alien, on realizing its true nature, be so violently aggressive? I say he'd keep running. Glazer does come up with a creepily affecting scene, where the lure meets a man with neurofibromatosis (Adam Pearson)--in an interview Pearson tells of how he helped Johansson come up with the right things to say and do to seduce him, and you can't help but develop a sense of uneasy dread as he responds to the come-on.

Not perhaps a complete success, but especially with that quietly lurid first part Glazer proves himself a more ambitious and more capable (if more pretentious) filmmaker than Besson. If you must have your daily dose of the actress I recommend the latter--you come away with something not so easily scrubbed off, even with a scouring pad. I know; I tried.

Monday, August 11, 2014

Vacation (The Sequel)

End of summer blues: posting an old 2011 piece on New York. Part one is here; the sequel is as follows:

My forays into New York aren't always about eating, and aren't always about film; sometimes I just want to re-visit locations that for me define the city, or at least define some of the most memorable ways man has put stone and steel to use.

Take Grand Central Terminal, shown below:

A view of the Hudson River and George Washington Bridge from Fort Tryon Park. I doubt if all the vegetation or forest is native to the area, but you do get some sense of what the island must have looked like before the settlers took over.

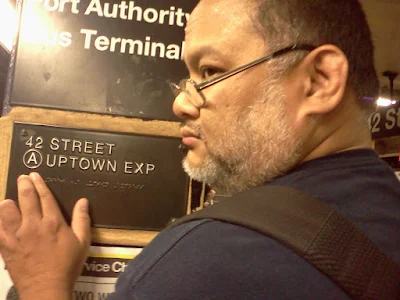

And sometimes the fascination doesn't involve an entire castle or river or park; sometimes it can be a detail as small as a subway sign--

My forays into New York aren't always about eating, and aren't always about film; sometimes I just want to re-visit locations that for me define the city, or at least define some of the most memorable ways man has put stone and steel to use.

Take Grand Central Terminal, shown below:

The soaring ceiling, once looked overgrown with dark moss, is now a bright green, thanks to an extensive restoration job; the at one time dull-brass stars are now gleaming constellations (a little hi-tech help from LED bulbs)--you think of gold coins glittering from the bottom of an upturned aquarium. The brass four-faced clock perched atop the center ticketing booth, the sunlight streaming down from barred cathedral windows--this Church to the Railway Gods with its unceasing buzz (it houses forty-four platforms connected to sixty-seven tracks, the largest train station in the world) is a drama few filmmakers can resist shooting (it's one of the most common images of the city on film). Not everyone has managed to justify their use of it, though; some of the most memorable include Terry Gilliam's The Fisher King (which magically transformed Grand Central into a grand ballroom full of waltzing commuters) and maybe Brian De Palma's Carlito's Way (which turned the terminal's escalators and tunnels into playground setting for a deadly game of tag).

Sometimes I feel like something quieter:

Sometimes I feel like something quieter:

The Cloisters in upper Manhattan seem like another world--you step out of the subway station, see a playground across the street, climb stone steps, find yourself in Fort Tryon Park. You take winding paths past flower beds and giant trees (surrounding rocky fort battlements with breathtaking views) to the highest elevation in the island, and finally to a monastic castle in part assembled from pieces of actual castles and monasteries, brought to the country stone by ancient stone.

The museum has an extensive collection of Medieval art and crafts including intricate silver and gold pieces (a gold-plated salt cellar, an early silver-and-rock-crystal fork with an uncomfortable resemblance to a dagger); it has a garden planted and laid out exactly as in a monastery, with plenty of herbs and medicinal plants (monks were a practical people who expected long periods of isolation, if not outright siege); it has beautiful examples of stained glass (including grisaille and bright-colored windows, some of which contain unforgettably vivid shades of deep yellow); and playing cards, oblong shaped and intricately drawn and colored (reminding me of Tarot cards--and why not? One's fate or fortune, decided by a draw from the pack).

Some of the most memorable sights uptown aren't found inside The Cloisters, but here:

A view of the Hudson River and George Washington Bridge from Fort Tryon Park. I doubt if all the vegetation or forest is native to the area, but you do get some sense of what the island must have looked like before the settlers took over.

And sometimes the fascination doesn't involve an entire castle or river or park; sometimes it can be a detail as small as a subway sign--

--complete with Braille dots and mounted for some reason on cork. Possibly one of the oldest in the city? Possibly.

Calling Katz Deli an institution doesn't help, does it? Even if Katz is a repository of New York Jewish foodcraft and artifacts, it's hardly a museum--not when people throng inside actively interacting with and consuming said artifacts.

I've tried other delis; love the fatty tenderness of New York pastrami, the richness of their chopped liver. It's just that Katz's hand-slices the pastrami (meaning the meat is just that much thicker yet oh-so-tender, and the outside crust of peppercorns crumbles and falls between the slices), and the chopped liver has...something (Liver? Boiled egg? Schmaltz, or rendered chicken fat? A combination of the three?)...mixed into it that makes it that much sweeter. A varied plate of pickles, a bottle of Dr. Brown's Celery Tonic (the vegetable-y soda offsets the taste of deli flesh), a slice of cheesecake (thick and creamy and faintly flavored of vanilla) and yes, I can die a happy, happy man.

And, yes, sometimes it isn't bad to spend a little money. We called M. Wells Diner, one of the hottest new restaurants in New York for a reservation.

"Ten o'clock?"

"It's the only one available."

"In the evening?"

"We'll call you back if anyone cancels."

In retrospect, I suppose we were lucky to get a reservation that same day. I remember listening to one man--he'd just finished dinner and was talking to the hostess--make a reservation for four in October.

At around 9.30 we took the 7 train, stepped out at Hunter's Point, looked around--and we were there. An old building offered steak and seafood, all shuttered up, and right beside it was this tiny diner car, all gleaming stainless steel. Pushed in the diner doors and were told we were too early.

So we sat outside, and waited. And waited. Ordered a lemonade, sipped it. Waited some more. Ten on the dot we stepped back inside, and no, the table still wasn't ready, so we waited at the entrance.

Mind you, that's just the time aspect, which felt infinite; I haven't even begun mentioning space, which was anything but. The diner was tiny, about the size of a sardine can if you took out all the sardines. The booths were jammed with customers, the counter seats stuffed with customers; the only appreciable free space was behind the counter, and with all the waiters and cooks and hot appliances bubbling and hissing and running about I doubt if our presence would be appreciated there either. I wondered stupidly: why don't they move into the building next door if they were so crowded? Knock out a wall, connect the two spaces, voila! Instant gratification. Wouldn't be the same, I suppose. A critic suggested the whole thing was 'performance art,' and I wouldn't be surprised; all that's missing is a gang of young actors hanging in a unisex restroom, lighting it up and talking about their next gig...

We were finally seated, some half an hour later--and here I might as well present a bit of history and philosophy: M. Wells is the brainchild of Sarah Obraitis and her husband Hugue Dufour, formerly of the famed Au Pied de Cochon, in Montreal. Dufour cooks and decorates his little eatery according to the principles of what you might call 'casual minimalist.' Just click on his website above: all you get is a photo featuring their name, their hours, phone number, address, email address, and not much more.

Note that they're open for brunch, but not weekends; according to one article, they don't have the facilities to serve the 200 diners weekend service would involve. Ballsy statement, assuming two hundred people would want to come on a weekend to what looks like an industrial neighborhood, all shut warehouses and not much else beyond the Long Island Expressway roaring nearby. That said, with this much crowd sitting and waiting to sit, you tend to believe them.

The menu was divided into small plates, big plates; we ordered four small, three big. The tomato tart was fresh tomatoes on nutty cheese on crackling crust--a perfect little pizza, only tastier. The Russian breakfast was blinis--crepelike pancakes--with caviar, creme fraiche, smoked sturgeon, simple and fresh. The lobster roll was chunks of lobster in a perfectly toasted roll (the textures--chew of lobster, creaminess of brown butter (with a hit of tarragon), crispness of bread--played like a light melody on the tongue). The escargot and bone marrow with shallots and red wine puree, served on half of a shank bone, was a spectacle to both eye and mouth: toothsome mollusks in the richest meat butter in the world, substance and style in every bite.

Big plates were exactly as advertised, really big food served in what I can only describe as ceramic tubs. This included roasted mackerel with fried gnocchi and ratatouille--not the little fish they stuff into cans; we had a huge slab of smoky fish draped into and barely fitting the little bathtub with firm, flaky flesh, the texture nicely offset by crisped gnocchi, the flavor by earthy vegetables.

The saddle of lamb with tahini and pomegranate molasses (what on earth is a 'saddle?' The pelvis?) is amazing--each slice has a different texture and flavor, from dark, smoky crust to sweet and juicy pink to tender chewy translucent tendon. It's like the roast transforms with every tap of the knife, the trick performed against a backdrop of slightly bitter tahini (say the main ingredient aloud, and the cavern opens into a subterranean wonderland) and tangy-sweet molasses (for contrast, and Middle Eastern flair).

Then there's the BibiM Wells, their version of the classic Korean bibimbap. The bibimbap I ate in Jeonju was Korean comfort food, sliced-and-diced vegetables and shredded beef over broth-flavored rice, with a fried egg on top for richness. This version was a seafood bounty: razor clams, scallops, gravlax, accompanied by julienned vegetables and fried yam chips that I kept mistaking for crisped bacon (I was thinking all the while that it was an odd if welcome touch, the addition of pork to the dish), all over fluffy steamed rice. Instead of fried egg for richness, foie gras; to tie it all together is the mildly spicy sweetness of a maple chili sauce.

"How is it?" the waitress asked.

"This shouldn't work," I said. "Gravlax, clams, scallops and foie gras? It's crazy. It should never work. But it does."

The waitress didn't seem pleased. Maybe I was babbling; maybe I came across as thoroughly pissed. I meant well.

I suggested dessert, but everyone was stuffed; they wouldn't hear of it. I pointed out that the blueberry pie behind us, doing a good imitation of a manhole-sized disc of cracked asphalt, was constantly shrinking as waitress after waitress hacked off hunks for customers. C. replied that all he wanted was to get up and walk a little or he would burst, literally. I suggested the maple pie, or how about the Paris-Brest, "a kind of funnel cake?" Everyone groaned in protest.

"Do waitresses get paid a lot?" La. asked.

"No, but add the tips and it's a decent wage. Why?"

"Because I'd like to work here someday."

Postscript: according to recent articles, M. Wells Diner will be closing down at the end of this month. Two thoughts come to my mind with the new: first, we were lucky to actually eat there, and second: that guy who made reservations for four in October--what's he going to do now?

8.21.11

I've tried other delis; love the fatty tenderness of New York pastrami, the richness of their chopped liver. It's just that Katz's hand-slices the pastrami (meaning the meat is just that much thicker yet oh-so-tender, and the outside crust of peppercorns crumbles and falls between the slices), and the chopped liver has...something (Liver? Boiled egg? Schmaltz, or rendered chicken fat? A combination of the three?)...mixed into it that makes it that much sweeter. A varied plate of pickles, a bottle of Dr. Brown's Celery Tonic (the vegetable-y soda offsets the taste of deli flesh), a slice of cheesecake (thick and creamy and faintly flavored of vanilla) and yes, I can die a happy, happy man.

And, yes, sometimes it isn't bad to spend a little money. We called M. Wells Diner, one of the hottest new restaurants in New York for a reservation.

"Ten o'clock?"

"It's the only one available."

"In the evening?"

"We'll call you back if anyone cancels."

In retrospect, I suppose we were lucky to get a reservation that same day. I remember listening to one man--he'd just finished dinner and was talking to the hostess--make a reservation for four in October.

At around 9.30 we took the 7 train, stepped out at Hunter's Point, looked around--and we were there. An old building offered steak and seafood, all shuttered up, and right beside it was this tiny diner car, all gleaming stainless steel. Pushed in the diner doors and were told we were too early.

So we sat outside, and waited. And waited. Ordered a lemonade, sipped it. Waited some more. Ten on the dot we stepped back inside, and no, the table still wasn't ready, so we waited at the entrance.

Mind you, that's just the time aspect, which felt infinite; I haven't even begun mentioning space, which was anything but. The diner was tiny, about the size of a sardine can if you took out all the sardines. The booths were jammed with customers, the counter seats stuffed with customers; the only appreciable free space was behind the counter, and with all the waiters and cooks and hot appliances bubbling and hissing and running about I doubt if our presence would be appreciated there either. I wondered stupidly: why don't they move into the building next door if they were so crowded? Knock out a wall, connect the two spaces, voila! Instant gratification. Wouldn't be the same, I suppose. A critic suggested the whole thing was 'performance art,' and I wouldn't be surprised; all that's missing is a gang of young actors hanging in a unisex restroom, lighting it up and talking about their next gig...

We were finally seated, some half an hour later--and here I might as well present a bit of history and philosophy: M. Wells is the brainchild of Sarah Obraitis and her husband Hugue Dufour, formerly of the famed Au Pied de Cochon, in Montreal. Dufour cooks and decorates his little eatery according to the principles of what you might call 'casual minimalist.' Just click on his website above: all you get is a photo featuring their name, their hours, phone number, address, email address, and not much more.

Note that they're open for brunch, but not weekends; according to one article, they don't have the facilities to serve the 200 diners weekend service would involve. Ballsy statement, assuming two hundred people would want to come on a weekend to what looks like an industrial neighborhood, all shut warehouses and not much else beyond the Long Island Expressway roaring nearby. That said, with this much crowd sitting and waiting to sit, you tend to believe them.

The menu was divided into small plates, big plates; we ordered four small, three big. The tomato tart was fresh tomatoes on nutty cheese on crackling crust--a perfect little pizza, only tastier. The Russian breakfast was blinis--crepelike pancakes--with caviar, creme fraiche, smoked sturgeon, simple and fresh. The lobster roll was chunks of lobster in a perfectly toasted roll (the textures--chew of lobster, creaminess of brown butter (with a hit of tarragon), crispness of bread--played like a light melody on the tongue). The escargot and bone marrow with shallots and red wine puree, served on half of a shank bone, was a spectacle to both eye and mouth: toothsome mollusks in the richest meat butter in the world, substance and style in every bite.

Big plates were exactly as advertised, really big food served in what I can only describe as ceramic tubs. This included roasted mackerel with fried gnocchi and ratatouille--not the little fish they stuff into cans; we had a huge slab of smoky fish draped into and barely fitting the little bathtub with firm, flaky flesh, the texture nicely offset by crisped gnocchi, the flavor by earthy vegetables.

The saddle of lamb with tahini and pomegranate molasses (what on earth is a 'saddle?' The pelvis?) is amazing--each slice has a different texture and flavor, from dark, smoky crust to sweet and juicy pink to tender chewy translucent tendon. It's like the roast transforms with every tap of the knife, the trick performed against a backdrop of slightly bitter tahini (say the main ingredient aloud, and the cavern opens into a subterranean wonderland) and tangy-sweet molasses (for contrast, and Middle Eastern flair).

Then there's the BibiM Wells, their version of the classic Korean bibimbap. The bibimbap I ate in Jeonju was Korean comfort food, sliced-and-diced vegetables and shredded beef over broth-flavored rice, with a fried egg on top for richness. This version was a seafood bounty: razor clams, scallops, gravlax, accompanied by julienned vegetables and fried yam chips that I kept mistaking for crisped bacon (I was thinking all the while that it was an odd if welcome touch, the addition of pork to the dish), all over fluffy steamed rice. Instead of fried egg for richness, foie gras; to tie it all together is the mildly spicy sweetness of a maple chili sauce.

"How is it?" the waitress asked.

"This shouldn't work," I said. "Gravlax, clams, scallops and foie gras? It's crazy. It should never work. But it does."

The waitress didn't seem pleased. Maybe I was babbling; maybe I came across as thoroughly pissed. I meant well.

I suggested dessert, but everyone was stuffed; they wouldn't hear of it. I pointed out that the blueberry pie behind us, doing a good imitation of a manhole-sized disc of cracked asphalt, was constantly shrinking as waitress after waitress hacked off hunks for customers. C. replied that all he wanted was to get up and walk a little or he would burst, literally. I suggested the maple pie, or how about the Paris-Brest, "a kind of funnel cake?" Everyone groaned in protest.

"Do waitresses get paid a lot?" La. asked.

"No, but add the tips and it's a decent wage. Why?"

"Because I'd like to work here someday."

Postscript: according to recent articles, M. Wells Diner will be closing down at the end of this month. Two thoughts come to my mind with the new: first, we were lucky to actually eat there, and second: that guy who made reservations for four in October--what's he going to do now?

8.21.11

Vacation (New York, 2011)

End of summer blues: a reposting of an old something I wrote about New York, back in 2011

So I took a week off and drove to New York.

Wasn't my first time this year; I'd already gone for a weekend to help introduce a pair off films in a small Filipino film festival--

And on my way to said festival stepped out of the Times Square subway station smack dab in the middle of the above rally. Syrian Americans demonstrating--peacefully but loudly--for support of pro-democracy forces. One of the ladies were kind enough to let me pose holding a posterboard (of Bashir Al-Assad, and one of the civilians killed by bombings).

"New York? How expensive!" Sure, unless you do things a little different--like booking a hotel out in Flushing, Queens which, aside from being safe at two in the morning (step out of the subway and you'll swear you're in Hong Kong, Kowloon side) has some of the best Chinese food this side of, well, Hong Kong.

Like the hand-pulled noodles in Golden Mall (41-28 Main Street, look carefully, it's easy to miss)--basically a building basement where the landlords have subdivided the floor space into tiny cubbyholes, and proprietors have set up folding tables and stools for people to sit.

You walk up (not even sure which stall I ended up in; there was a lot of spillover business it was that crowded); you point out what you want (I could speak some Mandarin, but this was beyond my meager vocabulary); you crouch balancing precariously on a folding stool meant for a six-year-old. I should know; I kept casting a wary eye on one seven-year-old having trouble with his seat.

Then your order comes and it's worth the time and bother and cramped sauna conditions. The soup comes in what can basically be described as a wash basin; the noodles had been pulled just minutes ago (you have to twist and stretch your neck above the counter to catch a glimpse, but it's quite a show--a blob of dough flattened, stretched, magically divided by a few swift hand movements into guitar strings); the chunks of lamb meat are fat and tender and tendon-y.

And the broth--thick, dark, deeply flavored by meat and green onion and god only knows what mysterious spices and herbs and essences go into this elixir (Is that anise I detect? Marrow distilled from shank bones, the richest, meatiest butter in the world?). Basically a little over five dollars for a bowl; worth it, if you don't count the bother of sharing your table with a half dozen other total strangers, and having to move out of the way every five minutes so delivery men shoving hand carts can whiz past you.

That's not the only cheap eats around. Not far from the corner of Kissena Avenue and Main Street is a Vietnamese restaurant that serves excellent pho (broth, noodles, beef shank and tendons, some innards, and--love this part--the freshest cilantro, basil leaves, lime wedges and bean sprout toppings available). Outside this place--wouldn't know if they are affiliated or not--is a sidewalk grill that serves grilled tripe, stomach, cheeks, what have you on skewers.

In the city I always go to a sidewalk stand across the Toys 'R Us store in Times Square. Order the beef kebab, and specify medium rare; they will ask if you want the kebab salted (say 'yes,' otherwise it's too bland). They will ask if you want it on a hotdog bun--that's okay by me, who cares? It's in my opinion the best piece of grilled meat in the city, tender, smoky, hot; when you bite, the blood gushes out and soaks the hotdog bun, the kind of leftover treat a carnivore dreams of in his wettest fantasies.

We'd gone into Kebab Cafe (2512 Steinway Ave in Queens) years ago, sometime in 2007, if I remember right, a tiny nook that could sit twenty if everyone dieted a month and used plenty of Vaseline, decorated all over with mosaics and tiny lamps and drawings and photos and posters and other bric-a-brac. Ali the owner had been particularly taken with A., and called him "my man!" We'd always meant to come back, but never had the chance.

We returned this month; Ali took one look at us, one look at A. and said "A., my man!" C. asked: "you remember, after all those years?" Ali said: "how could I forget?" I whispered to Lu. "He's got quite a memory."

We returned this month; Ali took one look at us, one look at A. and said "A., my man!" C. asked: "you remember, after all those years?" Ali said: "how could I forget?" I whispered to Lu. "He's got quite a memory."

Had us seated; asked us what we wanted to drink (we asked for the pomegranate soda--basically soda water with pomegranate syrup, not too sweet--while A. asked for a Coke); told us he'll take care of the food. Started the falafel mix, the baba ganoush, the hummus; formed the falafel balls with a pair of spoons, dropped them in hot oil. "I remember coming here years ago, because of that show by Bourdain," I said. Ali replied "Jamie Oliver visited too." "Oliver? Really? You're doing well, then." "Yes, but of course you people are much more important to me." Lu. leaned over to me and whispered "And he's still the flatterer."

I got up. "Where are you going?" "There's an ATM machine next door, right?" "Sit down, don't worry about that." Ali ordered. I sat down. He asked if C. wanted to learn how to cook; had him fan out slices of pear on a plate, then serve it to us: basically a mixed dish of baba ganoush, hummus and fava beans in lemon juice, with the sliced pear for picking up the thick dip and cleansing the palate.

Ali may have remembered A. but it was C. who asked all the (occasionally tactless) questions. At one point C. made an off-the-cuff remark about Egyptian culture, how primitive it must have been. I pointed out that Alexander the Great was inspired by Egyptian knowledge, that Imhotep possibly performed the first instance of brain surgery, that he was one of the first to use honey as a disinfectant because it was hygroscopic. Ali declared that "honey is an excellent preservative, and Imhotep is a genius for using it--but he is nothing compared to my man, Lapu-lapu!" He laid a plate of the fresh fried falafel before us, decorated with deep-fried bok choy.

When C. asked who Lapu-lapu was, Ali explained: "He was a Filipino who killed Ferdinand Magellan, the man who organized the first expedition to circle the world. The Europeans call him Magellan's killer but to Asians he's a freedom fighter, a hero." He put a plate of lamb cheeks before us, cracked an egg over it, and mixed it up with a spoon. It was terrific--rich and chewy and meaty all at the same time.

He even had a moment for La. "Oh, she's texting. Most guys don't care; they text out in the open. But girls like to text under the table, as if it were a secret. She likes to keep secrets."

Ali served us our final plate: fried cauliflower with pomegranate, the cauliflower coated with thick carmelized fruit sauce. We got up. "Next time I need to teach A. how to cook, it's his turn when you come back. And he should eat more--he's too skinny." Ali had lined up A., C., and even La. against the doorway leading to the bathroom, and marked their height. He said: "A., you better eat--I don't want to have you come back here shorter than when you came last."

He even had a moment for La. "Oh, she's texting. Most guys don't care; they text out in the open. But girls like to text under the table, as if it were a secret. She likes to keep secrets."

Ali served us our final plate: fried cauliflower with pomegranate, the cauliflower coated with thick carmelized fruit sauce. We got up. "Next time I need to teach A. how to cook, it's his turn when you come back. And he should eat more--he's too skinny." Ali had lined up A., C., and even La. against the doorway leading to the bathroom, and marked their height. He said: "A., you better eat--I don't want to have you come back here shorter than when you came last."

It was--I don't know, extraordinarily leisurely and relaxed and, well, affectionate--old friends meeting again, almost. No; better--like spending an afternoon with an eccentric but dear, rarely seen uncle, who served us in his living room, stretching his arm out of his little kitchen to lay the dishes on the table. One of the best meals we ever had.

(Next: Vacation the Sequel)

Tuesday, August 05, 2014

Guardians of the Galaxy (James Gunn, 2014); Begin Again (John Carney, 2013)

Oh, it's all over the papers, TV, internet: new Marvel superhero team movie; big boxoffice hit; Vin Diesel does funny tree impersonation (I mean, beside his own usually wooden visage); birth of successful new franchise in otherwise humdrum movie year.

Screw all that; screw Marvel, screw superheroes, screw movie franchises, screw Vin Diesel, screw the boxoffice. This is the new James Gunn picture that I've been waiting for for some eight years--and that's why I went to watch Guardians of the Galaxy. The rest can take a flying leap off of a speeding Kree warship.

Slither (James Gunn, 2006)

(Seeing as Mr. Gunn is now hot as pancakes, a 2006 article, to explain why I've had an eye on his work all this time)

Horribly funny

What with very real horrors readily visible in news broadcasts (from Iraq, for one), escapist horror seems the order of the day in the multiplexes. Last year there was Saw 2, Hostel, The Devil's Rejects, The Exorcism of Emily Rose, Dominion: Prequel to The Exorcist and remakes of House of Wax and The Amityville Horror among many others; this year there's The Hills Have Eyes and the just-released Silent Hill.

Maybe my biggest problem with all these slash-and-splat flicks is the lack of humor in them; solemn horror now being the dominion of Japanese filmmakers (I'm thinking of Hideo Nakata, whose The Ring Two was an underrated little gem, and Kurosawa Kyoshi, the best living practitioner of the genre in Japan--one of the best in the world, for that matter), most attempts by American directors to be taken seriously will end in a fit of giggles. American directors are better off going in a different direction--the 'horror comedy' for one, which requires the kind of aggressive irreverence for which they are particularly gifted (there's already been one early master, the British-born but Hollywood-based James Whale). American horror needs, in short, to be fun again.

James Gunn's Slithers is a mishmash of half-a-dozen titles including a few classics (the opening is straight out of the original The Blob), with references to half a dozen more, including Rosemary's Baby, The Thing, Basket Case, and Tremors (don't be intimidated by all the arcane allusions, though--there's plenty to cringe at, and laugh).

Nathan Fillion is Bill Pardy, a small-town sheriff in a police cruiser with too much time on his hands (his partner kills time by measuring the speed of passing birds with their radar gun). When things happen they happen fast: a meteorite crashes into the surrounding forests and the town's wealthiest man, Grant Grant (Michael Rooker) is infected by a needlelike lifeform that lodges in his lower skull. Grant develops an appetite for raw meat ("Gimme a couple of ribeyes…eight. Naw, ten. You know what? Gimme fourteen") and pet dogs, and develops unsightly rashes ("It's just a bee sting," he explains to wife Starla (Elizabeth Banks)).

Writer-director James Gunn has some experience in horror comedy (okay, he wrote the Scooby Doo movies--but also Tromeo and Juliet, and a few other Toxic Avenger installments). There's real wit in his setting the action in Wheelsy, a community so American Heartland small the bars play country music, the citizens gather for the official opening of hunting season, the town's most visible black man wears a collar and crucifix (probably why he was allowed to live there), and the sheriff's gun rack includes shotguns, automatic weaponry, and a grenade confiscated from some overambitious trout fisherman. America is being invaded by an enemy more insidious than mere terrorists: an alien whose reproductive organs parallel--worse, parody--ours (and we know with what perverse fascination these people regard sex outside of marriage, or even just outside of the missionary position). Gunn borrows an image or two (actually, whole sequences) from David Cronenberg: Grant grows tentacles, prompting one elderly townsfolk to describe him as looking like "something that fell off my dick during the war;" a hapless young woman (Brenda James) finds herself pregnant with alien life forms, swelling to enormous size (a swipe at America's obesity epidemic) and "hankering for a bit of possum;" bright-red slugs--resembling by turns tongues, phalluses, vigorously wriggling sperm cells--are unleashed, squirming their way through lawns, up walls, and (moist, meaty tails flicking and flailing) into people's gullets.

From an opening straight out of The Blob to alien biology inspired by Cronenberg, Gunn finally shifts to Romero, with zombies possessed by Grant's red slugs taking over the entire town. Gunn also happened to write the Dawn of the Dead remake, and while some critics approved of his speeded-up zombies, I didn't; they were more spastic than spooky, more desperate than serenely, unnervingly confident. These zombies, however, I do like--they remember their former selves, not enough to feel they have to switch sides, but enough to taunt the survivors and become genuine menaces; they also share Grant's identity, and it's not a little unsettling to hear him speak in stereo, from more than one corner of the room.

Through it all runs a romantic-triangle storyline that subverts the holiness of matrimony, then gets so compelling it subverts its own subversion. I'll explain: Grant's marriage is at first sight a sterile one--Starla chose Grant mainly for money and security; Grant chose Starla mainly because she was hot. When Grant turns monstrous and hides in the surrounding forests, Starla pleads with him to come back, saying theirs is a "sacred bond" that he has to recognize.

Strangely enough, Grant does; early in the picture he had an opportunity to be unfaithful with Brenda, but backs away (this was before the alien possessed him). Even when sporting several tentacles and a hideously deformed mouth (among other grotesqueries) Grant still accords Starla special treatment, fixing her up in a lovely white dress, then putting their favorite tune on the sound system (I'm embarrassed to say I even recognize the song--"Every Woman in the World," by Air Supply). The film overtly comes down in favor of affectionate adultery over exploitative matrimony, but not without a struggle: Michael Rooker's Grant Grant still manages to come across as hauntingly sweet, even touching, an unforgettable lover to say the least.

As for the rest of the cast--Nathan Fillion, who I remember best as captain of Serenity (in the Joss Whedon film of the same name), creeps, runs, leaps and more or less struggles through this physically exhausting film with winning aplomb; he may not be smart enough to always realize what's going on, but he is smart enough to insist that when the story of how a young girl (Tania Saulnier) saved his life is retold, he should be the hero. Elizabeth Banks is a touch too skinny for my taste, but nevertheless makes for a creamy damsel in distress/bestial love interest. Gregg Henry, a veteran of Brian De Palma films (not to mention De Palma's upcoming The Black Dahlia) and hardly a stranger to black and extremely bloody comedy, makes for a memorably grotesque town mayor.

Michael Rooker played the eponymous role in John McNaughton's Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer and what made his performance there (the finest of any actor in recent years, I thought) so memorable wasn't the violence (which was unsettling, even for a hardcore horror fan like me), but the shy gentleness. I was prepared to see Rooker's Henry as someone monstrous, even evil; I wasn't prepared to see him as someone almost capable of love. Rooker's hideously bloated Grant has a similar kind of found humanity, albeit on a broader, more cartoonish scale. Easily the best horror film I've seen this year.

(First published in Businessworld, 4/28/06)

What with very real horrors readily visible in news broadcasts (from Iraq, for one), escapist horror seems the order of the day in the multiplexes. Last year there was Saw 2, Hostel, The Devil's Rejects, The Exorcism of Emily Rose, Dominion: Prequel to The Exorcist and remakes of House of Wax and The Amityville Horror among many others; this year there's The Hills Have Eyes and the just-released Silent Hill.

Maybe my biggest problem with all these slash-and-splat flicks is the lack of humor in them; solemn horror now being the dominion of Japanese filmmakers (I'm thinking of Hideo Nakata, whose The Ring Two was an underrated little gem, and Kurosawa Kyoshi, the best living practitioner of the genre in Japan--one of the best in the world, for that matter), most attempts by American directors to be taken seriously will end in a fit of giggles. American directors are better off going in a different direction--the 'horror comedy' for one, which requires the kind of aggressive irreverence for which they are particularly gifted (there's already been one early master, the British-born but Hollywood-based James Whale). American horror needs, in short, to be fun again.

James Gunn's Slithers is a mishmash of half-a-dozen titles including a few classics (the opening is straight out of the original The Blob), with references to half a dozen more, including Rosemary's Baby, The Thing, Basket Case, and Tremors (don't be intimidated by all the arcane allusions, though--there's plenty to cringe at, and laugh).

Nathan Fillion is Bill Pardy, a small-town sheriff in a police cruiser with too much time on his hands (his partner kills time by measuring the speed of passing birds with their radar gun). When things happen they happen fast: a meteorite crashes into the surrounding forests and the town's wealthiest man, Grant Grant (Michael Rooker) is infected by a needlelike lifeform that lodges in his lower skull. Grant develops an appetite for raw meat ("Gimme a couple of ribeyes…eight. Naw, ten. You know what? Gimme fourteen") and pet dogs, and develops unsightly rashes ("It's just a bee sting," he explains to wife Starla (Elizabeth Banks)).

Writer-director James Gunn has some experience in horror comedy (okay, he wrote the Scooby Doo movies--but also Tromeo and Juliet, and a few other Toxic Avenger installments). There's real wit in his setting the action in Wheelsy, a community so American Heartland small the bars play country music, the citizens gather for the official opening of hunting season, the town's most visible black man wears a collar and crucifix (probably why he was allowed to live there), and the sheriff's gun rack includes shotguns, automatic weaponry, and a grenade confiscated from some overambitious trout fisherman. America is being invaded by an enemy more insidious than mere terrorists: an alien whose reproductive organs parallel--worse, parody--ours (and we know with what perverse fascination these people regard sex outside of marriage, or even just outside of the missionary position). Gunn borrows an image or two (actually, whole sequences) from David Cronenberg: Grant grows tentacles, prompting one elderly townsfolk to describe him as looking like "something that fell off my dick during the war;" a hapless young woman (Brenda James) finds herself pregnant with alien life forms, swelling to enormous size (a swipe at America's obesity epidemic) and "hankering for a bit of possum;" bright-red slugs--resembling by turns tongues, phalluses, vigorously wriggling sperm cells--are unleashed, squirming their way through lawns, up walls, and (moist, meaty tails flicking and flailing) into people's gullets.

From an opening straight out of The Blob to alien biology inspired by Cronenberg, Gunn finally shifts to Romero, with zombies possessed by Grant's red slugs taking over the entire town. Gunn also happened to write the Dawn of the Dead remake, and while some critics approved of his speeded-up zombies, I didn't; they were more spastic than spooky, more desperate than serenely, unnervingly confident. These zombies, however, I do like--they remember their former selves, not enough to feel they have to switch sides, but enough to taunt the survivors and become genuine menaces; they also share Grant's identity, and it's not a little unsettling to hear him speak in stereo, from more than one corner of the room.

Through it all runs a romantic-triangle storyline that subverts the holiness of matrimony, then gets so compelling it subverts its own subversion. I'll explain: Grant's marriage is at first sight a sterile one--Starla chose Grant mainly for money and security; Grant chose Starla mainly because she was hot. When Grant turns monstrous and hides in the surrounding forests, Starla pleads with him to come back, saying theirs is a "sacred bond" that he has to recognize.

Strangely enough, Grant does; early in the picture he had an opportunity to be unfaithful with Brenda, but backs away (this was before the alien possessed him). Even when sporting several tentacles and a hideously deformed mouth (among other grotesqueries) Grant still accords Starla special treatment, fixing her up in a lovely white dress, then putting their favorite tune on the sound system (I'm embarrassed to say I even recognize the song--"Every Woman in the World," by Air Supply). The film overtly comes down in favor of affectionate adultery over exploitative matrimony, but not without a struggle: Michael Rooker's Grant Grant still manages to come across as hauntingly sweet, even touching, an unforgettable lover to say the least.

As for the rest of the cast--Nathan Fillion, who I remember best as captain of Serenity (in the Joss Whedon film of the same name), creeps, runs, leaps and more or less struggles through this physically exhausting film with winning aplomb; he may not be smart enough to always realize what's going on, but he is smart enough to insist that when the story of how a young girl (Tania Saulnier) saved his life is retold, he should be the hero. Elizabeth Banks is a touch too skinny for my taste, but nevertheless makes for a creamy damsel in distress/bestial love interest. Gregg Henry, a veteran of Brian De Palma films (not to mention De Palma's upcoming The Black Dahlia) and hardly a stranger to black and extremely bloody comedy, makes for a memorably grotesque town mayor.

Michael Rooker played the eponymous role in John McNaughton's Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer and what made his performance there (the finest of any actor in recent years, I thought) so memorable wasn't the violence (which was unsettling, even for a hardcore horror fan like me), but the shy gentleness. I was prepared to see Rooker's Henry as someone monstrous, even evil; I wasn't prepared to see him as someone almost capable of love. Rooker's hideously bloated Grant has a similar kind of found humanity, albeit on a broader, more cartoonish scale. Easily the best horror film I've seen this year.

(First published in Businessworld, 4/28/06)

Saturday, August 02, 2014

The China Syndrome (James Bridges, 1979)

Old thrills

I suppose James Bridges' The China Syndrome (1979) owes its success big-time to timing--premiering days before the Three Mile Island incident, which probably gave the audiences the (mostly mistaken) impression that this was an expose of what really went down inside of those menacingly faceless and huge containment structures. Imagine their surprise when they sat down and realized it's another of Bridges' skillful little character studies, of ordinary folk trying to negotiate some kind of path between private ethics and public duties, which on their best days achieve some kind of uneasy, undulating truce.

Hard to imagine a thriller like this being made today--a look not just at the nuclear power industry but at broadcast news from a feminist point of view; a quick precis not just of nuclear power, fuel pellets and damping rods and all ("don't get too technical!") but of the industrial application of nuclear power complete with technical jargon ('SCRAM,' auxiliary feed valves, and the aforementioned eponymous syndrome--which turns out to be pretty damned bad, but not the radioactive apocalypse the film threatens to loose upon the world).

Meantime we have this, and Bridges' brilliant little touches making all not just palatable but compulsively watchable: the way the alarm blares during the first incident, for example, a loud mechanical shrieking in the ear that affirms the panic-pushing nature of all such alarms; then Godell (Jack Lemmon) demands the alarm be switched off ("How can anyone expect to think with that racket?"). The eerie silence that follows is far more disturbing, as if Brooks had presented the ear-splitting stereotype then suddenly took it away; we're in unknown territory now, the building's alien rumblings and workers' tense mutterings anything but reassuring.

Bridges shows more confidence in the scenes involving broadcast journalism--he started in television, after all--and in sketching the subsequent rise of ambitious TV reporter Kimberly Wells (Jane Fonda). Fonda nicely underplays the frustrations she feels at being held back, at being seen as nothing more than a pretty face and ass (she hates it but buys into it all the same, because that's the only way you succeed in television). At the same time the way Bridges skewers spineless TV producers and inane news segments and the industry's pervasive sexism helps keep the heavier industrial drama from sinking too far into solemnity.

Along the way Bridges cooks up inventive little sequences that show his gift for thrilling audiences without pandering to them--the kill-the-courier scene with deliberate parallels to the Karen Silkwood affair; the even better later chase sequence, where Godell outwits his shadowy would-be killers in a manner the politically liberal Bridges would've approved of--by simply following his everyday route to work, the everyman's knowledge of familiar territory trumping the predators' presumably superior skill at demolition driving.

For the film's climax Bridges (for better or worse) reasserts old values, in particular the primary one--the veteran broadcast worker's need and duty to transmit information, as clearly and succinctly as possible. Godell, a nuclear plant supervisor, wouldn't have a clue how to do this properly (and Wells is presumably too raw a neophyte, too caught up in the drama of the moment, too ignorant of the issues involved to keep him focused). How many thrillers climax with a race to get information--not weapons, not gold, not some high-ranking hostage (but in many ways more valuable than all three)--out to the general public? How many thrillers turn on the as-yet unanswered question of a broadcast announcer's ability to keep her shit together, remain calm enough to reassure the unseen audience that yes she knows what she's talking about?

At first glance the film isn't much to look at--all cold concrete and steel, when it isn't panning over Los Angeles' interstate highways. But Bridges throws entire arrays of blinking lights above our heads ('situation boards,' the PR flunky informs us, informing plant employees that some technical issue needs immediate attention), gives us grainy video footage of gigantic steel masses shuddering in near collapse. And above all the relentless unvarying chatter of the teletype, printing out in emotionless language the step-by-step details of an oncoming disaster.

I suppose James Bridges' The China Syndrome (1979) owes its success big-time to timing--premiering days before the Three Mile Island incident, which probably gave the audiences the (mostly mistaken) impression that this was an expose of what really went down inside of those menacingly faceless and huge containment structures. Imagine their surprise when they sat down and realized it's another of Bridges' skillful little character studies, of ordinary folk trying to negotiate some kind of path between private ethics and public duties, which on their best days achieve some kind of uneasy, undulating truce.

Hard to imagine a thriller like this being made today--a look not just at the nuclear power industry but at broadcast news from a feminist point of view; a quick precis not just of nuclear power, fuel pellets and damping rods and all ("don't get too technical!") but of the industrial application of nuclear power complete with technical jargon ('SCRAM,' auxiliary feed valves, and the aforementioned eponymous syndrome--which turns out to be pretty damned bad, but not the radioactive apocalypse the film threatens to loose upon the world).

Meantime we have this, and Bridges' brilliant little touches making all not just palatable but compulsively watchable: the way the alarm blares during the first incident, for example, a loud mechanical shrieking in the ear that affirms the panic-pushing nature of all such alarms; then Godell (Jack Lemmon) demands the alarm be switched off ("How can anyone expect to think with that racket?"). The eerie silence that follows is far more disturbing, as if Brooks had presented the ear-splitting stereotype then suddenly took it away; we're in unknown territory now, the building's alien rumblings and workers' tense mutterings anything but reassuring.

Bridges shows more confidence in the scenes involving broadcast journalism--he started in television, after all--and in sketching the subsequent rise of ambitious TV reporter Kimberly Wells (Jane Fonda). Fonda nicely underplays the frustrations she feels at being held back, at being seen as nothing more than a pretty face and ass (she hates it but buys into it all the same, because that's the only way you succeed in television). At the same time the way Bridges skewers spineless TV producers and inane news segments and the industry's pervasive sexism helps keep the heavier industrial drama from sinking too far into solemnity.

Along the way Bridges cooks up inventive little sequences that show his gift for thrilling audiences without pandering to them--the kill-the-courier scene with deliberate parallels to the Karen Silkwood affair; the even better later chase sequence, where Godell outwits his shadowy would-be killers in a manner the politically liberal Bridges would've approved of--by simply following his everyday route to work, the everyman's knowledge of familiar territory trumping the predators' presumably superior skill at demolition driving.

For the film's climax Bridges (for better or worse) reasserts old values, in particular the primary one--the veteran broadcast worker's need and duty to transmit information, as clearly and succinctly as possible. Godell, a nuclear plant supervisor, wouldn't have a clue how to do this properly (and Wells is presumably too raw a neophyte, too caught up in the drama of the moment, too ignorant of the issues involved to keep him focused). How many thrillers climax with a race to get information--not weapons, not gold, not some high-ranking hostage (but in many ways more valuable than all three)--out to the general public? How many thrillers turn on the as-yet unanswered question of a broadcast announcer's ability to keep her shit together, remain calm enough to reassure the unseen audience that yes she knows what she's talking about?

At first glance the film isn't much to look at--all cold concrete and steel, when it isn't panning over Los Angeles' interstate highways. But Bridges throws entire arrays of blinking lights above our heads ('situation boards,' the PR flunky informs us, informing plant employees that some technical issue needs immediate attention), gives us grainy video footage of gigantic steel masses shuddering in near collapse. And above all the relentless unvarying chatter of the teletype, printing out in emotionless language the step-by-step details of an oncoming disaster.

Friday, August 01, 2014

Snowpiercer (Bong Joon-ho, 2013)

Runaway

Bong Joon-ho's Snowpiercer is every which way ridiculous judging from the premise: the earth has frozen over from a global-warming cure gone horribly wrong; all that's left of humanity are the occupants of a mile-long train, riding endlessly up and down the rails of the planet.

Why a train? As opposed to, say, a city or island or mountain retreat, all of which consume less energy and are easier to maintain? Why must the train keep moving? What keeps the train moving (only power source I can think of that lasts seventeen years is a nuclear reactor, in which case where's the shielding?)? Why is there an underclass, and why are they treated so badly?

Bong's achievement is to drive the narrative forward so that one by one--like so many hanky-waving well-wishers--each question is left behind, rendered irrelevant, even forgotten. One of the biggest though (why a train?) is granted an answer, a startling reply with disturbing implications.

On the most basic storytelling level we have this fantastical to the point of impossible rail adventure, the siderodromophiliac's ultimate wet dream. Toss in an epic car-to-car battle involving hatchets, torches, automatic weaponry, and the odd IED--enough mayhem to call this one of the most entertaining pictures of 2014 (actually 2013, but the Weinsteins had intervened).