Dreck on wheels

Death Proof (2007), Quentin Tarantino's contribution to the Grindhouse omnibus released together in the USA earlier this year, is having its solo premiere in Manila's commercial theaters. How does this slightly longer version play, so many months later?

Pretty much the same. Tarantino has added a few minutes of eye candy--Vanessa Ferlito manages to do her lap dance for Kurt Russell (who luckily isn't wearing his Escape from New York eyepatch) instead of having the entire scene written off as a 'missing reel' (the film for those that need the explanation replicates every aspect of the grindhouse theater experience including scratched prints, mismatched footage (the film's midpoint sequence is in black and white), and lost scenes). Russell later manages to caress Rosario Dawson's dangling toes while passing her car door ("He accidentally brushed against my feet. It was creepy"); I'm assuming the director is indulging his fetish for feet (many of the women wear flip-flops or walk about shoeless or prop said limbs up high at the slightest excuse, purely for our delectation) and perhaps Latina women (Russell closely studies Ferlito's lap dance, enjoys the feel of Dawson's soles).

Tarantino does his level best to reproduce '70s style cinematography, from the garish colors to the bright lighting to the racking focus practiced by Laszlo Kovacs and Vilmos Zsigmond. More anachronistic are the stealthy tracking shots that glide across rooms past people and furniture (a trademark move by a director who (presumably) likes the sense of foreboding), not to mention the numerous long takes of people speaking pages of his dialogue to each other.

The dialogue--Tarantino's talk is more or less enjoyable, but the rhythms, the way his people chat and curse have become (from the eight previous feature films I've seen) terribly familiar. "You know," says Stuntman Mike (Kurt Russell), "how people say 'You're okay in my book' or 'In my book, that's no good?' Well, I actually have a book. And everybody I ever meet goes in this book. And now I've met you, and you're going in the book." Rhythm and repetition and recycled twists of syntax are the tricks of his trade, the word 'book' like a regular beat to each sentence (my book, a book, this book), the word 'have' a kind of exclamation point changing the nature of the statement, referring not just to a theoretical 'book' but an actual, physical object Russell produces in his hand. Said dialogue can be funny ("I don't wear their teeth marks on my butt for nothing"), it can be chilling ("It would have been a while before you started getting scared"), but it all sounds as if it had been spoken by the same mouth, composed by the same mind. Tarantino really needs to listen more to the great variety of speech patterns and accents found in the United States at the very least, maybe throw in a foreign accent or three, maybe even a deaf-mute (maybe not; his Bride in Kill Bill, Vol. 1 didn't talk, and she was a dull, dull girl before she was allowed to express herself more in Kill Bill Vol. 2).

I've always declared that Tarantino was a better writer than filmmaker, and perhaps a genius at casting (John Travolta in Pulp Fiction; Robert Forster and Pam Grier in Jackie Brown, David Carradine in Kill Bill Vol. 2)), that his default style (sinuous or static long takes) was mostly a way for him to present his dialogue properly. The first half of Death Proof doesn't do much to change my assessment--talk, talk, talk, mostly in the one bar, with maybe Ferlito's lap dance thrown in to relieve the verbiage. Midpoint in the movie, when Russell's Chevy Nova smashes into an oncoming car, the collision is all repeated slow motion and (I'm assuming) digitally enhanced carnage (a severed leg, a tire wheel literally rubbing someone's face out). The second setpiece sequence, a faceoff between Russell in a Dodge Charger and a second set of girls in a white Dodge Challenger ("Kowalski!" exclaims Tracie Thoms, recognizing the reference to Richard Serafian's great 1971 road movie Vanishing Point) is a different creature altogether; I wouldn't blame anyone for skipping the film's first hour to sit in at this far superior second one, a duel between two muscle car classics that's shot (far as I can see) entirely without computer effects or even an undercranked camera--just real cars racing at real speeds, a real stuntwoman (Bell playing herself) clinging with near-real panic to the hood of the car.

As an advertisement for feminine empowerment the movie is a dodgy proposition: we're asked to accept the dismembering of the first set of girls by Russell's Stuntman Mike as setup for the second set of girls to take vengeance, with the second set's main justification for surviving being that they don't do booze or drugs, that two of them (like Mike) are professional stuntmen, and (most importantly) that one of them (Thoms) carries a gun. An earlier exchange between the girls ("You can't get around the fact that people who carry guns, tend to get shot more than people who don't." "And you can't get around the fact that if I go down to the laundry room in my building at midnight enough times, I might get my ass raped.") is entirely justified by Mike's appearance on the scene ("See?" you can imagine the less skeptical in the audience pointing out to each other, "Good thing they were packing."). I won't go so far as say Tarantino is anti-gun control, only that he's simply following the anarchically amoral conventions of the genre; it follows, then, that just because an innocent biker gets brutally thrown against a roadside signboard and the girls leave one of their own (Lee, played by Mary Elizabeth Winstead, whose only crime seems to be a serious case of stupidity) behind, presumably to be raped, one shouldn't be upset; such elements are only to be expected in these kinds of pictures.

Sure, fine; whatever. Perhaps my biggest problem with this tribute to those kinds of pictures is that it seems so superfluous, at least to us Filipinos. We have grindhouse-type theaters showing grindhouse-type fare, in Cubao, in Manila; we have prints full of scratches and missing reels, moldering away in our unairconditioned warehouses. We have politically incorrect movies--brutal rapes, shameless melodramas, slipshod action vehicles, rubbery monster suits splashing about in gallons of patently faux blood (for some reason, possibly budgetary (and for all I know they've since corrected this), our fake blood is pinker than Hollywood's) of a number and variety to rival any American filmmakers' most outrageous, most perverse tastes.

Here comes Tarantino spending over thirty million dollars (over sixty if you count Robert Rodriguez's contribution) faking what we've been doing for decades and you want to ask--couldn't he just hand all that money over directly to our filmmakers instead? It would be less trouble for everyone all around.

(Published in Businessworld 12/14/07)

Friday, December 28, 2007

Wednesday, December 26, 2007

'Tis the season

'Tis the season to overindulge--in my neck of the woods, to stuff one's self full of baked goods. I'd pretty much had them all: fudgy, green-icinged, candy-sprinkled, oatmealed-and-raisined, you name it. I've had lemon coolers and Russian Tea Cookies; I've had horrifying monstrosities of an unappetizingly green hue that resembled something from a short story by Isaac Asimov (strangely enough the creatures--actually marshmallow-and-cornflake treats that for some reason had been dyed a bright lime green--were rather appetizing). Terry--not my wife or girlfriend, just my housemate (don't ask, it's complicated)--was doing a batch for her sister; some days earlier, the sister had been wondering what to do for the cookie exchange she had agreed to join (apparently in this part of rural America such exchanges are common); I suggested lengua de gato, a crisp little treat I used to love as a child. "Everyone and their sister will be baking chocolate chip cookies--maybe oatmeal, if they're imaginative," I said. "Lengua de gato would be something they'd never seen before."

It was not to be, but we did get a box full of other people's produce out of it (one of which is the aforementioned shapeless, green-tinted treat), and a large tupperware full of Terry's leftover cookies: simple chocolate chip, oatmeal, and (simplest of all) sugar cookies that were nice and crisp--almost like a lengua. Call it consuelo de bobo (rough translation: moron's consolation), but I was happy with what I had.

Have to admit, I went totally nuts this year, and I don't mean just cookies. Went to a wine shop to buy a red (for my spaghetti sauces), a bottle of Marsala (for cream sauces and desserts), and a gift for Terry's sister's friend when I looked up at the shelf behind the cash register and spotted a familiar label. "Is that Dom Perignon?" I asked. "Yes," said the cashier." "How much?" "A hundred and forty nine dollars." "Well," I said, after picking my jaw up off the floor, "that's about the size of our holiday dinner budget, I suppose," and found myself for some weird reason actually reaching for my wallet. Before I realized what had happened, I found myself sitting in the car with not three but four bottles clinking away in the rear seat.

A few nights later, I was wondering what would go well with that bottle of Dom--cheese? Strawberries? Not bad choices, but I stumbled upon this website, and couldn't help clicking on a few links--whole duck liver: seventy-one dollars. Not that I had seventy dollars lying about to spend on just anything I wanted (and with overnight shipping--a must, considering the item--the grand total was a clean hundred dollars), but a) it's Christmas, and b) for once I could actually afford to buy it without worrying about my electricty getting cut off (again, don't ask). Reason 'a' wasn't all that simple a reason; I loathe Christmas and could care less about celebrating the damned thing...but I've spent too many years (the last five to ten, in fact) under a tight financial leash and a self-pitying funk during the holidays and thought: what the hell--if I'm expected to indulge, I might as well go all the way. I was a weak and unprincipled sinner all last week, you betcha.

The liver arrived exactly five days later (three days for processing then overnight delivery), in a styro box, sitting on cold packs; beside the pale creamy lobes was a pair of duck breasts. I suppose I should be grateful, though I don't remember breasts ever being mentioned in my order form--but never mind; they were a bother and a distraction, but I might as well use 'em. If no one at the dinner table wanted to actually try medium-rare duck liver, the breasts might actually come in handy as some kind of backup dish.

The night before Christmas I was struggling to make a fruit compote--for the liver of course (I hadn't even begun to think about the duck breast); the Dom was chilling away in the fridge. I'd downloaded a recipe, was about to pour my just-bought bottle of Marala into a bowl full of sugar and chopped fruit (peaches, pears, plums, strawberries, dried apricots, dried figs, candied ginger, mint sprigs), when I realized that the recipe called for Madeira wine. Should I just use what I bought? I don't know Marsala from Madeira from manure, which was kind of the point--I didn't feel confident enough to try a substitution. So I sent Terry out to buy a bottle which she did (patient and angelic temperament that she had); the whole watery mess went into a large gallon bowl, which in turn went into a fridge.

Terry stood behind me while I was pouring. "What's all that for?" "Oh, just a compote for the duck liver." "You're going through all that trouble just for liver?" "It's very special liver. It cost seventy dollars, plus a pair of duck breasts." That shut her up for a moment, out of sheer astonishment. "Well," she said, "I was thinking of making my egg rolls too." "Sure, why don't you do that? Just in case."

D-day dawned, and my compote was mixed one more time in early morning (I'd been mixing it every few hours the previous night). I'd also dug up an easy duck breast recipe involving dried cherry sauce, only I didn't have any dried cherries--searched high and low, nope, nothing. Was acutely aware that not a single store was open this Christmas day (actualy I also had a problem with the toasted bread that was supposed to go with the duck liver--but that was a whole other issue).

Took out my 12-inch nonstick, put the breasts in it scored-skin down for four minutes; turned them over, did it again for another four minutes, then transferred the breasts into a baking dish to finish in the oven at 400 degrees for ten minutes. In the nonstick pan tossed in the 'cherry sauce'--half a cup of red wine, half a cup of chicken broth, a tablespoon of vinegar, a tablespoon of sugar, salt and pepper, and instead of cherries I threw in the half cup of craisins (dried cranberries) I found hiding in someone's ziploc snack bag, reduce for eight minutes; add two tablespoons of butter to finish.

Then the scary part: with a knife kept continually moist by dipping it in running water, I cut roughly half-inch slices from the duck liver (had to be careful to keep it from breaking apart); added butter to a medium high pan (which immediately started smoking, setting off alarms), and as quickly added the duck liver. Counted to sixty, gingerly lifted the browned slices off the pan and into a serving plate--and came away with roughly eight beautifully browned (only on one side) medallions of pan-seared foie gras, one of the most luxurious foods in the world.

Laid a foie gras on one side of a plate, spooned fruit compote at the liver's one end, garnished with a mint sprig; laid a duck breast on the other side of the plate, spooned craisin sauce at the breast's other end, and yelled "COME AN' GIT IT, 'FORE I THROW IT OUT!" Each plate came with a glass of Dom Perignon.

The medallions were crispy brown one side, unbelievably creamy the other; the sweet, tart compote crunchy with fresh fruit cut through the richness nicely. The duck breast had crisped skin and a red, rare meat, and the craisin sauce complemented that perfectly, too. The Dom was dry and cold, and washed down all that decadence nicely.

Only there was something missing...the texture was there, but the flavor was lacking somehow. It was when I bit into the duck breast, feeling the crunch! of skin against teeth and the skin's strong flavor that I realized what I'd forgotten to do, the most basic step of all: add salt and pepper before you cook the meat.

"Holy--" I ran to the serving dish, sprinkled salt and pepper on the slices; put salt out on the table for everyone to use. But it was too late; the damned hundred dollar's worth of breast and liver was tastewise flat as pancakes. Hundred dollar pancakes, in effect.

Oh, I'd salvaged something from the experience--Picked up two leftover slices of foie gras, salt-and-peppered the uncooked side, seared them for a minute, then invited everyone to taste. Oohhs, and ahhs all around, this time sincere; they finally realized what it was all about. Ah, well. Maybe next year I can afford to do this again--do it right.

Just before I went to sleep some time after midnight, I felt a hankering for something to eat before I turned in. Not foie gras--that was all gone; not duck breast--that was much too rich. Something simple and homely and good.

I noticed Terry's egg rolls, sitting cold on a plate. I picked one up, dipped it in its vinegar and crushed garlic sauce, bit. The flavor of ground pork, chicken and shrimp flooded my mouth, the sweetness of pork and shrimp sharpened by the hint of soy, sesame oil, scallion, coriander leaf; and I could feel the crunch of the wonton wrapper, the crispness of the chopped water chestnuts. Not fancy, not expensive--just time-consuming and painstakingly difficult to make, a real labor of love, and the single best piece of food I tasted that night.

It was not to be, but we did get a box full of other people's produce out of it (one of which is the aforementioned shapeless, green-tinted treat), and a large tupperware full of Terry's leftover cookies: simple chocolate chip, oatmeal, and (simplest of all) sugar cookies that were nice and crisp--almost like a lengua. Call it consuelo de bobo (rough translation: moron's consolation), but I was happy with what I had.

Have to admit, I went totally nuts this year, and I don't mean just cookies. Went to a wine shop to buy a red (for my spaghetti sauces), a bottle of Marsala (for cream sauces and desserts), and a gift for Terry's sister's friend when I looked up at the shelf behind the cash register and spotted a familiar label. "Is that Dom Perignon?" I asked. "Yes," said the cashier." "How much?" "A hundred and forty nine dollars." "Well," I said, after picking my jaw up off the floor, "that's about the size of our holiday dinner budget, I suppose," and found myself for some weird reason actually reaching for my wallet. Before I realized what had happened, I found myself sitting in the car with not three but four bottles clinking away in the rear seat.

A few nights later, I was wondering what would go well with that bottle of Dom--cheese? Strawberries? Not bad choices, but I stumbled upon this website, and couldn't help clicking on a few links--whole duck liver: seventy-one dollars. Not that I had seventy dollars lying about to spend on just anything I wanted (and with overnight shipping--a must, considering the item--the grand total was a clean hundred dollars), but a) it's Christmas, and b) for once I could actually afford to buy it without worrying about my electricty getting cut off (again, don't ask). Reason 'a' wasn't all that simple a reason; I loathe Christmas and could care less about celebrating the damned thing...but I've spent too many years (the last five to ten, in fact) under a tight financial leash and a self-pitying funk during the holidays and thought: what the hell--if I'm expected to indulge, I might as well go all the way. I was a weak and unprincipled sinner all last week, you betcha.

The liver arrived exactly five days later (three days for processing then overnight delivery), in a styro box, sitting on cold packs; beside the pale creamy lobes was a pair of duck breasts. I suppose I should be grateful, though I don't remember breasts ever being mentioned in my order form--but never mind; they were a bother and a distraction, but I might as well use 'em. If no one at the dinner table wanted to actually try medium-rare duck liver, the breasts might actually come in handy as some kind of backup dish.

The night before Christmas I was struggling to make a fruit compote--for the liver of course (I hadn't even begun to think about the duck breast); the Dom was chilling away in the fridge. I'd downloaded a recipe, was about to pour my just-bought bottle of Marala into a bowl full of sugar and chopped fruit (peaches, pears, plums, strawberries, dried apricots, dried figs, candied ginger, mint sprigs), when I realized that the recipe called for Madeira wine. Should I just use what I bought? I don't know Marsala from Madeira from manure, which was kind of the point--I didn't feel confident enough to try a substitution. So I sent Terry out to buy a bottle which she did (patient and angelic temperament that she had); the whole watery mess went into a large gallon bowl, which in turn went into a fridge.

Terry stood behind me while I was pouring. "What's all that for?" "Oh, just a compote for the duck liver." "You're going through all that trouble just for liver?" "It's very special liver. It cost seventy dollars, plus a pair of duck breasts." That shut her up for a moment, out of sheer astonishment. "Well," she said, "I was thinking of making my egg rolls too." "Sure, why don't you do that? Just in case."

D-day dawned, and my compote was mixed one more time in early morning (I'd been mixing it every few hours the previous night). I'd also dug up an easy duck breast recipe involving dried cherry sauce, only I didn't have any dried cherries--searched high and low, nope, nothing. Was acutely aware that not a single store was open this Christmas day (actualy I also had a problem with the toasted bread that was supposed to go with the duck liver--but that was a whole other issue).

Took out my 12-inch nonstick, put the breasts in it scored-skin down for four minutes; turned them over, did it again for another four minutes, then transferred the breasts into a baking dish to finish in the oven at 400 degrees for ten minutes. In the nonstick pan tossed in the 'cherry sauce'--half a cup of red wine, half a cup of chicken broth, a tablespoon of vinegar, a tablespoon of sugar, salt and pepper, and instead of cherries I threw in the half cup of craisins (dried cranberries) I found hiding in someone's ziploc snack bag, reduce for eight minutes; add two tablespoons of butter to finish.

Then the scary part: with a knife kept continually moist by dipping it in running water, I cut roughly half-inch slices from the duck liver (had to be careful to keep it from breaking apart); added butter to a medium high pan (which immediately started smoking, setting off alarms), and as quickly added the duck liver. Counted to sixty, gingerly lifted the browned slices off the pan and into a serving plate--and came away with roughly eight beautifully browned (only on one side) medallions of pan-seared foie gras, one of the most luxurious foods in the world.

Laid a foie gras on one side of a plate, spooned fruit compote at the liver's one end, garnished with a mint sprig; laid a duck breast on the other side of the plate, spooned craisin sauce at the breast's other end, and yelled "COME AN' GIT IT, 'FORE I THROW IT OUT!" Each plate came with a glass of Dom Perignon.

The medallions were crispy brown one side, unbelievably creamy the other; the sweet, tart compote crunchy with fresh fruit cut through the richness nicely. The duck breast had crisped skin and a red, rare meat, and the craisin sauce complemented that perfectly, too. The Dom was dry and cold, and washed down all that decadence nicely.

Only there was something missing...the texture was there, but the flavor was lacking somehow. It was when I bit into the duck breast, feeling the crunch! of skin against teeth and the skin's strong flavor that I realized what I'd forgotten to do, the most basic step of all: add salt and pepper before you cook the meat.

"Holy--" I ran to the serving dish, sprinkled salt and pepper on the slices; put salt out on the table for everyone to use. But it was too late; the damned hundred dollar's worth of breast and liver was tastewise flat as pancakes. Hundred dollar pancakes, in effect.

Oh, I'd salvaged something from the experience--Picked up two leftover slices of foie gras, salt-and-peppered the uncooked side, seared them for a minute, then invited everyone to taste. Oohhs, and ahhs all around, this time sincere; they finally realized what it was all about. Ah, well. Maybe next year I can afford to do this again--do it right.

Just before I went to sleep some time after midnight, I felt a hankering for something to eat before I turned in. Not foie gras--that was all gone; not duck breast--that was much too rich. Something simple and homely and good.

I noticed Terry's egg rolls, sitting cold on a plate. I picked one up, dipped it in its vinegar and crushed garlic sauce, bit. The flavor of ground pork, chicken and shrimp flooded my mouth, the sweetness of pork and shrimp sharpened by the hint of soy, sesame oil, scallion, coriander leaf; and I could feel the crunch of the wonton wrapper, the crispness of the chopped water chestnuts. Not fancy, not expensive--just time-consuming and painstakingly difficult to make, a real labor of love, and the single best piece of food I tasted that night.

Tuesday, December 18, 2007

Eastern Promises (David Cronenberg, 2007)

Tattoo you

Eastern Promises (2007) is the story of Anna (Naomi Watts) a midwife working at a London hospital who helps a 14-year-old Russian girl (Sarah-Jeanne Labrosse) deliver her child. The young mother dies, leaving behind the infant girl and a diary; Anna, who is part Russian, adopts diary and child and sets out to discover what had happened to the mother.

Her quest leads her to the Trans-Siberian, a restaurant owned by Semyon (Armin Meuller-Stahl); Semyon is all grandfatherly charm, offering to translate the diary; Anna is hesitant--her uncle Stepan (Polish filmmaker Jerzy Skolimowsky) tells her to stay away from the vory v zakone (thieves in law), the Russian mafia, of which Semyon is the apparent local leader. Part and parcel of Semyon's organizational apparatus is his chauffer-slash-foot soldier Nikolai (Viggo Mortensen), whose primary assignment is guarding Semyon's alcoholically unstable son, Kiril (Vincent Cassell). Will Anna translate the diary and protect the girl? Will she develop affection for, perhaps even a bond with, Nikolai, or will Kiril (who's just dripping with suppressed desires) get to him first? Will Semyon be brought to justice, the young girl avenged?

What do you think? The script is by Steve Wright, who also wrote the screenplay to Stephen Frears' Dirty Pretty Things (2002) and like that earlier film it's concerned with European immigrants and the way they feed off of each other and struggle to survive. I wasn't that big a fan of Frears' film--thought it (thanks in no small part to Frears' verite visual style) presented a grim enough predicament, but also a solution far too pat and tidy to be believable. Likewise with his script for Eastern--it draws us into a strange world and gives us enough details that we'd be hooked, but later depends on such unlikely devices as a woman's implacable sense of justice, a man's furtive sense of obligation, another man's implausible sense of outrage (on exactly what he is or is not capable of doing) to arrive at a (to Wright's mind, anyway) satisfying denouement. Wright has his heart in its rightful place; it's just his way of getting there that feels so wrong.

Enter Cronenberg, arguably one of the stranger, less sentimental filmmakers around. If I may trot out an old argument I've been making, like fellow master of the bizarre David Lynch he has strong feelings about sex and sexuality; unlike Lynch (a boy scout of a man who believes in the innocence and corruption of the world with equal fervor), there's little that's naïve in Cronenberg; unlike Lynch, who as often as not refuses to close in on the horrific imagery (or if he does, he inserts it briefly into the big screen, like a retinal flash) he's a pornographer of horror who prefers to show every gynecological detail of his monstrosities in all their pulsating glory.

Lately he's moved away from straight horror and into the realm of straight drama--without, I submit, losing that sense of unblinking strangeness that is the hallmark of all his films. Cronenberg, gazing upon a man's face and not some outsized vaginal orifice, seems to regarded that face as if it were a vaginal orifice, and still manages to communicate his sense of alienated unease to us, sans prosthetic makeup.

Hence, the strangeness of the film. Wright wrote a a tearjerker asking us to cry for a poor little prostitute and her hard-luck life; Cronenberg took the script and turned it into a meditation on the perversities inflicted on the human body. A teenage girl stands unsteadily in a drugstore, faints in a pool of her own blood; a man is kept frozen in a freezer, thawed out with a hairdryer, has his frosty fingers snipped off; another strips naked standing in a ring of old men, in an arcane ritual evoking everything from James Woods declaring fealty to the New Flesh in Cronenberg's Videodrome (1983) to Jeremy Irons in scarlet high-priest robes, ready to perform medical alchemy in Dead Ringers (1988). The naked man's body, incidentally, is covered with intricate tattoos (in the Russian mafia, tattoos not only identify a person, it tells his story--where he came from, what he's gone through, who he's affiliated with) and Cronenberg's camera gazes upon those tattoos as if they were some Ballardian message inscribed by aliens, or worse; a message waiting for us to translate it, with no guarantee at all that we will like what we read.

As the medium for that message and Cronenberg's actor of choice nowadays when it comes to internally conflicted, externally stoic protagonists, Viggo Mortensen gives a marvelous performance. It isn't just the accent, delivered with Meryl Streeplike skill; Mortenson moves differently in this film, moves like a cautious, courtly Russian who knows he has to navigate carefully through a strange city; his sense of alienation from the culture and society around him, his inability to treat anything and anyone outside of his "family" with any amount of ease (he's perhaps at his most comfortable with Kiril, his boss' sociopathic son, who happens to be in love with him) turns him into our default surrogate--our eyes, in effect--in this world made just a tad unreal by virtue of being filtered through Cronenberg's sensibilities.

Cronenberg mentions that he wanted to avoid guns in the film, and I think he's right to do so--knives are so much more precise in the kind of damage they can do to human flesh as demonstrated in his setpiece action sequence, an attempted assassination in a bathhouse. The sequence (an attempted rape by Kyril by way of Semyon?) has some of the homoerotic poetry of the sauna murder in Orson Welles' great Othello (1952), some of the complex fight choreography and stuntwork of the climactic prison shower riot in Mario O'Hara's Kastilyong Buhangin (Castle of Sand, 1980--well, perhaps not as intricate as the riot; O'Hara was working with stuntman-turned-star Lito Lapid and his daredevil colleagues, and they were given carte blanche to do pretty much whatever they wanted (and on wet tiles, yet!))--some of the sense of bloodletting and violated flesh of a Cronenberg film. Not a perfect production, not by a long shot, but a fascinating, fascinating work, nevertheless.

(First published in Businessworld 12.7.07)

Eastern Promises (2007) is the story of Anna (Naomi Watts) a midwife working at a London hospital who helps a 14-year-old Russian girl (Sarah-Jeanne Labrosse) deliver her child. The young mother dies, leaving behind the infant girl and a diary; Anna, who is part Russian, adopts diary and child and sets out to discover what had happened to the mother.

Her quest leads her to the Trans-Siberian, a restaurant owned by Semyon (Armin Meuller-Stahl); Semyon is all grandfatherly charm, offering to translate the diary; Anna is hesitant--her uncle Stepan (Polish filmmaker Jerzy Skolimowsky) tells her to stay away from the vory v zakone (thieves in law), the Russian mafia, of which Semyon is the apparent local leader. Part and parcel of Semyon's organizational apparatus is his chauffer-slash-foot soldier Nikolai (Viggo Mortensen), whose primary assignment is guarding Semyon's alcoholically unstable son, Kiril (Vincent Cassell). Will Anna translate the diary and protect the girl? Will she develop affection for, perhaps even a bond with, Nikolai, or will Kiril (who's just dripping with suppressed desires) get to him first? Will Semyon be brought to justice, the young girl avenged?

What do you think? The script is by Steve Wright, who also wrote the screenplay to Stephen Frears' Dirty Pretty Things (2002) and like that earlier film it's concerned with European immigrants and the way they feed off of each other and struggle to survive. I wasn't that big a fan of Frears' film--thought it (thanks in no small part to Frears' verite visual style) presented a grim enough predicament, but also a solution far too pat and tidy to be believable. Likewise with his script for Eastern--it draws us into a strange world and gives us enough details that we'd be hooked, but later depends on such unlikely devices as a woman's implacable sense of justice, a man's furtive sense of obligation, another man's implausible sense of outrage (on exactly what he is or is not capable of doing) to arrive at a (to Wright's mind, anyway) satisfying denouement. Wright has his heart in its rightful place; it's just his way of getting there that feels so wrong.

Enter Cronenberg, arguably one of the stranger, less sentimental filmmakers around. If I may trot out an old argument I've been making, like fellow master of the bizarre David Lynch he has strong feelings about sex and sexuality; unlike Lynch (a boy scout of a man who believes in the innocence and corruption of the world with equal fervor), there's little that's naïve in Cronenberg; unlike Lynch, who as often as not refuses to close in on the horrific imagery (or if he does, he inserts it briefly into the big screen, like a retinal flash) he's a pornographer of horror who prefers to show every gynecological detail of his monstrosities in all their pulsating glory.

Lately he's moved away from straight horror and into the realm of straight drama--without, I submit, losing that sense of unblinking strangeness that is the hallmark of all his films. Cronenberg, gazing upon a man's face and not some outsized vaginal orifice, seems to regarded that face as if it were a vaginal orifice, and still manages to communicate his sense of alienated unease to us, sans prosthetic makeup.

Hence, the strangeness of the film. Wright wrote a a tearjerker asking us to cry for a poor little prostitute and her hard-luck life; Cronenberg took the script and turned it into a meditation on the perversities inflicted on the human body. A teenage girl stands unsteadily in a drugstore, faints in a pool of her own blood; a man is kept frozen in a freezer, thawed out with a hairdryer, has his frosty fingers snipped off; another strips naked standing in a ring of old men, in an arcane ritual evoking everything from James Woods declaring fealty to the New Flesh in Cronenberg's Videodrome (1983) to Jeremy Irons in scarlet high-priest robes, ready to perform medical alchemy in Dead Ringers (1988). The naked man's body, incidentally, is covered with intricate tattoos (in the Russian mafia, tattoos not only identify a person, it tells his story--where he came from, what he's gone through, who he's affiliated with) and Cronenberg's camera gazes upon those tattoos as if they were some Ballardian message inscribed by aliens, or worse; a message waiting for us to translate it, with no guarantee at all that we will like what we read.

As the medium for that message and Cronenberg's actor of choice nowadays when it comes to internally conflicted, externally stoic protagonists, Viggo Mortensen gives a marvelous performance. It isn't just the accent, delivered with Meryl Streeplike skill; Mortenson moves differently in this film, moves like a cautious, courtly Russian who knows he has to navigate carefully through a strange city; his sense of alienation from the culture and society around him, his inability to treat anything and anyone outside of his "family" with any amount of ease (he's perhaps at his most comfortable with Kiril, his boss' sociopathic son, who happens to be in love with him) turns him into our default surrogate--our eyes, in effect--in this world made just a tad unreal by virtue of being filtered through Cronenberg's sensibilities.

Cronenberg mentions that he wanted to avoid guns in the film, and I think he's right to do so--knives are so much more precise in the kind of damage they can do to human flesh as demonstrated in his setpiece action sequence, an attempted assassination in a bathhouse. The sequence (an attempted rape by Kyril by way of Semyon?) has some of the homoerotic poetry of the sauna murder in Orson Welles' great Othello (1952), some of the complex fight choreography and stuntwork of the climactic prison shower riot in Mario O'Hara's Kastilyong Buhangin (Castle of Sand, 1980--well, perhaps not as intricate as the riot; O'Hara was working with stuntman-turned-star Lito Lapid and his daredevil colleagues, and they were given carte blanche to do pretty much whatever they wanted (and on wet tiles, yet!))--some of the sense of bloodletting and violated flesh of a Cronenberg film. Not a perfect production, not by a long shot, but a fascinating, fascinating work, nevertheless.

(First published in Businessworld 12.7.07)

Friday, December 14, 2007

Tukso (Temptation, Dennis Marasigan, 2007)

Fracturing reality

Dennis Marasigan's Tukso (Temptation, 2007) from a script by himself, Mara Paulina Marasigan and Nikki Torres, is his sophomore effort at filmmaking following his marvelous adaptation of Tony Perez's Sa North Diversion Road (North Diversion Road, 2005), and it's evident he knows a thing or two about filmmaking, or at least film editing. The first few minutes--images of a fall, of talking heads, of silence and foreboding--are cut together with a strong sense of drama; Marasigan has had a long career in theater, and the showman's flair gained through long experience has helped, I think. He doesn't simply escalate the intensity of the imagery; he knows when to pause, to prolong, to punch home with the right words for maximum impact.

I'd go so far as to say that "Tukso" is proof positive that Marasigan wasn't just coasting on the excellence of Perez's classic theatrical piece but possesses a talent for filmmaking all his own. Perez's play posed special challenges--how do you present a theatrical conceit (two actors playing ten different characters) on the big screen? Onstage the constant shift of story and setting kept the viewers off-balance, guessing at what's happening and what's going to happen, and this held their interest for the play's relatively short performance time; onscreen you only had to change car, costume, highway exit and it's obvious where you are, who you're with, and why. Marasigan solves this by shifting emphasis away from said conceit and relying on purely cinematic devices--employing a restless cutting style that maintained the tension, shooting (on the near-nonexistent budget these digital films usually enjoy) from as many angles as he can manage, treating the car as a little theater venue (the windshield and side windows act as surrounding proscenium arches), using stylization (special lighting and costumes and even acting styles) when necessary, and essentially leaving center stage clear for his two lead actors (John Arcilla and Marasigan's wife Irma Adlawan) to shine (not as easy a feat as you might imagine--tempting for a first-time director to try show off, demonstrate how much he's learned from his cinematographer, film textbook, DVD collection).

With Tukso the challenge is in a way even greater--how to stimulate (again with a tiny budget) visual interest in a screenplay that evokes memories of a legendary Japanese film (Akira Kurosawa's Rashomon (1952)). He draws from documentary and crime procedural conventions (including those used in Kurosawa's film)--the talking heads, the overlapping event (in this case, a woman leaving her lover's Range Rover), even the falling woman that opens the film. Does he succeed? Not quite, but it's a worthy effort.

Perhaps the picture's biggest problem is in allowing itself to be compared to Kurosawa's unforgettable statement on the unreliability of perception and impossibility of objective truth (this isn't even the first Filipino film to make the attempt--there's Laurice Guillen's Salome in 1981). It plays the game cleverly, in no small part thanks to Marasigan's talent as filmmaker, but doesn't play it cleverly enough--the testimony of each witness, for example, includes scenes that he or she can't possible have seen or known, or more crucially would never admit to an investigating officer of the law (Shamaine Buencamino); some clues practically scream out portent and significance (doors slowly closing on the camera lenses, implying that the people behind them are Up To No Good). It's a brave attempt but unlike, say, Brian De Palma's stylish thrillers, which gleefully invite comparisons to Hitchcock, it isn't able to present to us a fully persuasive justification for its homage--an entertaining spin on a classic tale, say, or a way of taking the original's premise a step beyond where the earlier picture was prepared to go.

All that said, the script is a clever enough construction, and in a genre that Philippine cinema rarely if ever tackles (I can't remember Lino Brocka or Ishmael Bernal ever doing a whodunit thriller, myself; when Mario O'Hara did try something in that area with Condemned (1984) it was I thought a well-done but rather minor element in a memorable noir vision)--kudos to Marasigan, then, for at least doing a decent execution, for keeping the whole complex plot coherent in his head, that he may transfer it with full clarity into ours.

But it's in the details of mood and tone and character that Marasigan excels--the way, say, Bal (Soliman Cruz), looks at his daughter Monica (Diana Malahay) in a manner that sends spiders crawling up your spine (Rashomon, meet Mike de Leon's in my opinion far more unsettling Kisapmata (Blink of an Eye, 1981)); or the way ambitious architect student Carlo (Sid Lucero) looks charmingly fresh-faced in one scene (when receiving praise for his work), distant and duplicitous in the next (thinking of Monica while embracing fiancé Gail (Anna Deroca)); or the way Gail's father David (the always excellent Ricky Davao) smiles while his eyes steal sidelong glances at Carlos and Monica, calculating possibilities, dangers, consequences.

Might as well add that one might accuse Marasigan of nepotism re: Ms. Adlawan for the way he seems to find her roles in his films, but the plain truth is that Ms. Adlawan is one of the best if not the best actress working in Philippine cinema today (one only has to see her brief but vivid moment as Virginia Parumog in Tikoy Aguiluz's Bagong Bayani (The Last Wish, 1995), or as the suffering Perla--raped physically, then metaphorically--in Jeffrey Jeturian's Tuhog (Larger than Life, 2001), or most impressively as half the acting coup in Marasigan's own Sa North Diversion Road). Adlawan here gives arguably the film's finest performance as Fe, the spinster who desires Emer (an also excellent Ping Medina (let's face it, the entire cast is terrific)), Monica's childhood friend (and unrequited admirer). With a few sidelong glances and a tentative way of delivering her lines, the actress effortlessly sketches for us a soul tormented by loneliness, attempting to reach out to someone incapable of seeing her as a woman, a sexual being. Tukso isn't quite as impressive as Sa North Diversion Road--easily one of the best of the Filipino digital films I've seen to date--but it's impressive enough, and it shows the growth and development of a promising filmmaker.

First published in Businessworld 12.7.07)

Dennis Marasigan's Tukso (Temptation, 2007) from a script by himself, Mara Paulina Marasigan and Nikki Torres, is his sophomore effort at filmmaking following his marvelous adaptation of Tony Perez's Sa North Diversion Road (North Diversion Road, 2005), and it's evident he knows a thing or two about filmmaking, or at least film editing. The first few minutes--images of a fall, of talking heads, of silence and foreboding--are cut together with a strong sense of drama; Marasigan has had a long career in theater, and the showman's flair gained through long experience has helped, I think. He doesn't simply escalate the intensity of the imagery; he knows when to pause, to prolong, to punch home with the right words for maximum impact.

I'd go so far as to say that "Tukso" is proof positive that Marasigan wasn't just coasting on the excellence of Perez's classic theatrical piece but possesses a talent for filmmaking all his own. Perez's play posed special challenges--how do you present a theatrical conceit (two actors playing ten different characters) on the big screen? Onstage the constant shift of story and setting kept the viewers off-balance, guessing at what's happening and what's going to happen, and this held their interest for the play's relatively short performance time; onscreen you only had to change car, costume, highway exit and it's obvious where you are, who you're with, and why. Marasigan solves this by shifting emphasis away from said conceit and relying on purely cinematic devices--employing a restless cutting style that maintained the tension, shooting (on the near-nonexistent budget these digital films usually enjoy) from as many angles as he can manage, treating the car as a little theater venue (the windshield and side windows act as surrounding proscenium arches), using stylization (special lighting and costumes and even acting styles) when necessary, and essentially leaving center stage clear for his two lead actors (John Arcilla and Marasigan's wife Irma Adlawan) to shine (not as easy a feat as you might imagine--tempting for a first-time director to try show off, demonstrate how much he's learned from his cinematographer, film textbook, DVD collection).

With Tukso the challenge is in a way even greater--how to stimulate (again with a tiny budget) visual interest in a screenplay that evokes memories of a legendary Japanese film (Akira Kurosawa's Rashomon (1952)). He draws from documentary and crime procedural conventions (including those used in Kurosawa's film)--the talking heads, the overlapping event (in this case, a woman leaving her lover's Range Rover), even the falling woman that opens the film. Does he succeed? Not quite, but it's a worthy effort.

Perhaps the picture's biggest problem is in allowing itself to be compared to Kurosawa's unforgettable statement on the unreliability of perception and impossibility of objective truth (this isn't even the first Filipino film to make the attempt--there's Laurice Guillen's Salome in 1981). It plays the game cleverly, in no small part thanks to Marasigan's talent as filmmaker, but doesn't play it cleverly enough--the testimony of each witness, for example, includes scenes that he or she can't possible have seen or known, or more crucially would never admit to an investigating officer of the law (Shamaine Buencamino); some clues practically scream out portent and significance (doors slowly closing on the camera lenses, implying that the people behind them are Up To No Good). It's a brave attempt but unlike, say, Brian De Palma's stylish thrillers, which gleefully invite comparisons to Hitchcock, it isn't able to present to us a fully persuasive justification for its homage--an entertaining spin on a classic tale, say, or a way of taking the original's premise a step beyond where the earlier picture was prepared to go.

All that said, the script is a clever enough construction, and in a genre that Philippine cinema rarely if ever tackles (I can't remember Lino Brocka or Ishmael Bernal ever doing a whodunit thriller, myself; when Mario O'Hara did try something in that area with Condemned (1984) it was I thought a well-done but rather minor element in a memorable noir vision)--kudos to Marasigan, then, for at least doing a decent execution, for keeping the whole complex plot coherent in his head, that he may transfer it with full clarity into ours.

But it's in the details of mood and tone and character that Marasigan excels--the way, say, Bal (Soliman Cruz), looks at his daughter Monica (Diana Malahay) in a manner that sends spiders crawling up your spine (Rashomon, meet Mike de Leon's in my opinion far more unsettling Kisapmata (Blink of an Eye, 1981)); or the way ambitious architect student Carlo (Sid Lucero) looks charmingly fresh-faced in one scene (when receiving praise for his work), distant and duplicitous in the next (thinking of Monica while embracing fiancé Gail (Anna Deroca)); or the way Gail's father David (the always excellent Ricky Davao) smiles while his eyes steal sidelong glances at Carlos and Monica, calculating possibilities, dangers, consequences.

Might as well add that one might accuse Marasigan of nepotism re: Ms. Adlawan for the way he seems to find her roles in his films, but the plain truth is that Ms. Adlawan is one of the best if not the best actress working in Philippine cinema today (one only has to see her brief but vivid moment as Virginia Parumog in Tikoy Aguiluz's Bagong Bayani (The Last Wish, 1995), or as the suffering Perla--raped physically, then metaphorically--in Jeffrey Jeturian's Tuhog (Larger than Life, 2001), or most impressively as half the acting coup in Marasigan's own Sa North Diversion Road). Adlawan here gives arguably the film's finest performance as Fe, the spinster who desires Emer (an also excellent Ping Medina (let's face it, the entire cast is terrific)), Monica's childhood friend (and unrequited admirer). With a few sidelong glances and a tentative way of delivering her lines, the actress effortlessly sketches for us a soul tormented by loneliness, attempting to reach out to someone incapable of seeing her as a woman, a sexual being. Tukso isn't quite as impressive as Sa North Diversion Road--easily one of the best of the Filipino digital films I've seen to date--but it's impressive enough, and it shows the growth and development of a promising filmmaker.

First published in Businessworld 12.7.07)

Sunday, December 09, 2007

Sight and Sound (and my own) Best Films of 007

Sight and Sound Magazine's Best Films of 2007

Includes the list of at least two Filipino film critics--Alexis Tioseco and, heh, yours truly. My titles (in alphabetical order) below:

Death in the Land of Encantos (Lav Diaz)

Eastern Promises (David Cronenberg)

Foster Child (Brillante Mendoza)

We Own the Night (James Gray)

Zodiac (David Fincher)

That's just the list, with articles I wrote on each film linked when available; to read the brief comments I'd written for Sight and Sound (plus the lists of better known critics) you'll need to download the largish PDF file.

Just a minor cavil about the lists; I'd been made aware that my list should consist only of films released in 2007. Now I know the UK sometimes exhibits certain films late, and I'd actually submitted some titles hoping I can sneak in some that I saw in the Jeonju Film Festival, but nope; strictly 2007 was the reply. So I made my list accordingly.

Now that I flip over that massive (47 pages long) PDF file, I learned that people had submitted films from 2006, even works by Mikio Naruse (I love Naruse, but no way no matter how great a filmmaker he is did he make a film in 2007). The whole brouhaha made me want to raise a brow and ask: "what's going on here?"

But I'm being ungrateful. It's an honor to have been asked to make a list, and I'm proud--tickled bright pink--to be in the company of Geoff Andrew, Derek Malcolm, Adrian Martin, Olaf Moller, Tony Rayns, Brad Stevens, Alexis Tioseco. Our lists are very different, showing a vast range of taste and orientation, and that's all to the good; we need the variety.

Anyway--if I had to make a list of films I'd seen in 2007 that had possibly been released or had yet not been released in the UK in the same year (this being the rule I presume Sight and Sound is following, and that anything released in 2006 possibly qualifes), this is what it would look like (in alphabetical order):

Amazing Life of the Fast Food Grifters (Mamoru Oshii)

Away From Her (Sarah Polley)

Before the Devil Knows You're Dead (Sidney Lumet) - Who knew Lumet had so much juice in him? I liked Dog Day Afternoon, I enjoyed Deathtrap (I know, I know--bite me), but this is possibly one of his best works, showing more grace and expressiveness, I think, than the entire oeuvre of the Coen brothers combined.

Bug (William Friedkin)

Colossal Youth (Pedro Costas)

Death in the Land of Encantos (Lav Diaz)

The Diving Bell and the Butterfly (Julian Schnabel)

Eastern Promises (David Cronenberg)

Exiled (Johnnie To)

The Go Master (Tian Zhuangzhuang)

Heremias Book One: The Legend of the Lizard Princess (Lav Diaz)

Indio Nacional (Raya Martin)

Inland Empire (David Lynch)

No Country For Old Men (Joel and Ethan Coen) - Not bad, easily one of their most entertaining. Can't take it more seriously than that, thanks to Bardem's effective but outlandish demon assassin--but it's a fun time in the movies, if your tastes go that way (and mine do, somewhat, for better or worse).

The Other Half (Ying Liang)

Paranoid Park (Gus Van Sant)

A Prairie Home Companion (Robert Altman)

Rescue Dawn (Werner Herzog)

Salty Air (Alessandro Angelini)

Sweeny Todd (Tim Burton) - a triumph of emotional and visual textures, a wonderful realization by Dante Ferretti of Victorian London by way of Eddie Campbell. Johnny Depp plays Todd like a berserk Edward Scissorhands, a Dark Knight with a taste for straight razors, an Ed Wood with a real talent for mayhem; his singing is more acting than belting, a way of burrowing into his character to find the massive malevolence within.

There Will Be Blood (Paul Thomas Anderson)

Todo Todo Teros (John Torres)

We Own the Night (James Gray)

The Wind that Shakes the Barley (Ken Loach)

Zodiac (David Fincher)

And that's all she said--unless I have a chance to see Brian de Palma's Redacted, to check out for myself what the fuss about them is all about.

Includes the list of at least two Filipino film critics--Alexis Tioseco and, heh, yours truly. My titles (in alphabetical order) below:

Death in the Land of Encantos (Lav Diaz)

Eastern Promises (David Cronenberg)

Foster Child (Brillante Mendoza)

We Own the Night (James Gray)

Zodiac (David Fincher)

That's just the list, with articles I wrote on each film linked when available; to read the brief comments I'd written for Sight and Sound (plus the lists of better known critics) you'll need to download the largish PDF file.

Just a minor cavil about the lists; I'd been made aware that my list should consist only of films released in 2007. Now I know the UK sometimes exhibits certain films late, and I'd actually submitted some titles hoping I can sneak in some that I saw in the Jeonju Film Festival, but nope; strictly 2007 was the reply. So I made my list accordingly.

Now that I flip over that massive (47 pages long) PDF file, I learned that people had submitted films from 2006, even works by Mikio Naruse (I love Naruse, but no way no matter how great a filmmaker he is did he make a film in 2007). The whole brouhaha made me want to raise a brow and ask: "what's going on here?"

But I'm being ungrateful. It's an honor to have been asked to make a list, and I'm proud--tickled bright pink--to be in the company of Geoff Andrew, Derek Malcolm, Adrian Martin, Olaf Moller, Tony Rayns, Brad Stevens, Alexis Tioseco. Our lists are very different, showing a vast range of taste and orientation, and that's all to the good; we need the variety.

Anyway--if I had to make a list of films I'd seen in 2007 that had possibly been released or had yet not been released in the UK in the same year (this being the rule I presume Sight and Sound is following, and that anything released in 2006 possibly qualifes), this is what it would look like (in alphabetical order):

Amazing Life of the Fast Food Grifters (Mamoru Oshii)

Away From Her (Sarah Polley)

Before the Devil Knows You're Dead (Sidney Lumet) - Who knew Lumet had so much juice in him? I liked Dog Day Afternoon, I enjoyed Deathtrap (I know, I know--bite me), but this is possibly one of his best works, showing more grace and expressiveness, I think, than the entire oeuvre of the Coen brothers combined.

Bug (William Friedkin)

Colossal Youth (Pedro Costas)

Death in the Land of Encantos (Lav Diaz)

The Diving Bell and the Butterfly (Julian Schnabel)

Eastern Promises (David Cronenberg)

Exiled (Johnnie To)

The Go Master (Tian Zhuangzhuang)

Heremias Book One: The Legend of the Lizard Princess (Lav Diaz)

Indio Nacional (Raya Martin)

Inland Empire (David Lynch)

No Country For Old Men (Joel and Ethan Coen) - Not bad, easily one of their most entertaining. Can't take it more seriously than that, thanks to Bardem's effective but outlandish demon assassin--but it's a fun time in the movies, if your tastes go that way (and mine do, somewhat, for better or worse).

The Other Half (Ying Liang)

Paranoid Park (Gus Van Sant)

A Prairie Home Companion (Robert Altman)

Rescue Dawn (Werner Herzog)

Salty Air (Alessandro Angelini)

Sweeny Todd (Tim Burton) - a triumph of emotional and visual textures, a wonderful realization by Dante Ferretti of Victorian London by way of Eddie Campbell. Johnny Depp plays Todd like a berserk Edward Scissorhands, a Dark Knight with a taste for straight razors, an Ed Wood with a real talent for mayhem; his singing is more acting than belting, a way of burrowing into his character to find the massive malevolence within.

There Will Be Blood (Paul Thomas Anderson)

Todo Todo Teros (John Torres)

We Own the Night (James Gray)

The Wind that Shakes the Barley (Ken Loach)

Zodiac (David Fincher)

And that's all she said--unless I have a chance to see Brian de Palma's Redacted, to check out for myself what the fuss about them is all about.

Saturday, December 08, 2007

Tukso (Temptation, Dennis Marasigan, 2007)

Excerpt:

Dennis Marasigan's Tukso (Temptation, 2007) from a script by the director, Mara Paulina Marasigan and Nikki Torres, is his sophomore effort at filmmaking after his marvelous adaptation of Tony Perez's Sa North Diversion Road (North Diversion Road, 2005), and it's evident he knows a thing or two about filmmaking, or at least film editing. The first few minutes--images of a fall, of talking heads, of silence and foreboding--are cut together with a strong sense of drama; Marasigan has had a long career in theater, and the showman's flair gained through long experience has helped, I think. He doesn't simply escalate the intensity of the imagery; he knows when to pause, to prolong, to punch home with the right words for maximum impact.

Friday, December 07, 2007

Fred Claus (David Dobkin, 2007)

O Christmas flick, o Christmas flick

To the people responsible for the picture;

This is a bad movie. No, I agree, you don't need people telling you it's bad; you need them telling you just how bad. Let me put it this way: if you churned this up and spread it in a field like any other fertilizer, nothing would grow. No self-respecting seed would sprout in manure this rank.

So how did your collective wits come up with the idea that Santa (Paul Giamatti) should have an older brother Fred (Vince Vaughn) who works as a Repo Man in Chicago, and that he should help out this holiday season? I mean, whatever you were sniffing--could you get me some? Has to be good, I think, to scramble your brains so thoroughly that this is what you managed to come up with. Yes, I know that in the Philippines turnaround time for making movies, from story idea to finished script to first commercial screening is maybe three months, four at most, and that the result is an incoherent, often unwatchable mess--what's your excuse?

Director David Dobkin gives the movie all the depth and visual flash of a Christmas card (not even a Hallmark Christmas card); the cast's acting is in two distinct styles: chew-the-scenery desperate (Vaughn, Giamatti, and Kevin Spacey as villain) or stand-about-like-mannequins clueless (Rachel Weisz and Elizabeth Banks as the undeniably pretty love interests (though what a beautiful woman with an English accent is doing in Chicago as a meter maid--and why the filmmakers didn't at least try and get comic mileage out of that--I haven't the slightest clue)). The special effects are standard-issue CGI--even Tim Allen's Santa Clause franchise had more convincing effects (and I loathe those pictures); the message is standard-issue holiday crap, about feeling good about oneself and doing a bit of good for others. "Peace on Earth, goodwill to all men"--Hollywood movies champion these values with such blatant, unembarrassed hypocrisy that you want to convert to Judaism, Buddhism, Communism, Satanism, anything to get away from the mosquito whine.

There are exactly two funny jokes in the picture: Fred attending a Siblings Anonymous meeting with Frank Stallone, Stephen Baldwin, Roger Clinton; and Kevin Spacey's Clyde Northcut, efficiency expert, standing triumphant and about ready to put a kibosh on Christmas when Santa looks him squarely in the eye, recognizes him, and says: "I should have given you the Superman cape you asked for in 1968…"

Otherwise--zilch, nada, nothing. If comedy was an ocean and a good joke a drink of water, this picture is the far side of the moon in terms of moisture.

But really, who's to fault you filmmakers? You only follow where the money is, like hyenas to rotting meat. The real villain is the season itself, corrupted by a lust for dollars, pesos, euros, yen, yuan to pad out retail stores' end-of-the-year cash balances. Just look at the moral of the movie--is it "love thy brother?" Hell, no; it's "gift-giving is important, even if one has to force a thousand little callused hands to work all night (and are they being paid overtime?), send a traditional winter conveyance with no aerodynamically viable means of motive force whizzing all over the world blind to do it." Everyone must have a gift by Christmas morning (note the emphasis on a deadline; cash on hand, in financial terms, is always more valuable than cash promised); otherwise, Santa's shop will be deemed a failure, and closed down (ironic, considering Santa is probably the biggest, most blatant symbol of capitalism this side of McDonald's and Disney).

It's not as if the birth of Christ, which all this is allegedly about, is all that important, at least not on the Catholic calendar. Far as they're concerned, the start of the Yuletide season three weeks before Christmas (at American shopping malls the season starts after Thanksgiving; at Filipino malls it starts on the "ber" months--September, October, November) is merely the start of the Liturgical Year; it's almost incidental that this also happens to be the birth of the Church's main protagonist (and not even the actual, historical birth--that probably happened around springtime). The year's true climax, theologically speaking, is Easter, when said protagonist's mission is fulfilled ("It is accomplished!" he says in the Gospel of John).

But none of this is news, of course. I suppose I’m being tiresome, pointing out how the commemoration of a simple birth in a Middle-Eastern country (and isn't it ironic that the attention of the world is back again on that region, after all is said and done?) has grown all out of proportion into this monstrous carcass of temple-priest commercialism, bloated with gas, heaving with maggots, just stuffed full of holiday goodness and cheer. I leave you with this simple thought: rotted corpses burst, eventually, and those closest to the body, feeding on its long-dead flesh, will be inundated. You have been warned.

Signed

The Grinch.

To the people responsible for the picture;

This is a bad movie. No, I agree, you don't need people telling you it's bad; you need them telling you just how bad. Let me put it this way: if you churned this up and spread it in a field like any other fertilizer, nothing would grow. No self-respecting seed would sprout in manure this rank.

So how did your collective wits come up with the idea that Santa (Paul Giamatti) should have an older brother Fred (Vince Vaughn) who works as a Repo Man in Chicago, and that he should help out this holiday season? I mean, whatever you were sniffing--could you get me some? Has to be good, I think, to scramble your brains so thoroughly that this is what you managed to come up with. Yes, I know that in the Philippines turnaround time for making movies, from story idea to finished script to first commercial screening is maybe three months, four at most, and that the result is an incoherent, often unwatchable mess--what's your excuse?

Director David Dobkin gives the movie all the depth and visual flash of a Christmas card (not even a Hallmark Christmas card); the cast's acting is in two distinct styles: chew-the-scenery desperate (Vaughn, Giamatti, and Kevin Spacey as villain) or stand-about-like-mannequins clueless (Rachel Weisz and Elizabeth Banks as the undeniably pretty love interests (though what a beautiful woman with an English accent is doing in Chicago as a meter maid--and why the filmmakers didn't at least try and get comic mileage out of that--I haven't the slightest clue)). The special effects are standard-issue CGI--even Tim Allen's Santa Clause franchise had more convincing effects (and I loathe those pictures); the message is standard-issue holiday crap, about feeling good about oneself and doing a bit of good for others. "Peace on Earth, goodwill to all men"--Hollywood movies champion these values with such blatant, unembarrassed hypocrisy that you want to convert to Judaism, Buddhism, Communism, Satanism, anything to get away from the mosquito whine.

There are exactly two funny jokes in the picture: Fred attending a Siblings Anonymous meeting with Frank Stallone, Stephen Baldwin, Roger Clinton; and Kevin Spacey's Clyde Northcut, efficiency expert, standing triumphant and about ready to put a kibosh on Christmas when Santa looks him squarely in the eye, recognizes him, and says: "I should have given you the Superman cape you asked for in 1968…"

Otherwise--zilch, nada, nothing. If comedy was an ocean and a good joke a drink of water, this picture is the far side of the moon in terms of moisture.

But really, who's to fault you filmmakers? You only follow where the money is, like hyenas to rotting meat. The real villain is the season itself, corrupted by a lust for dollars, pesos, euros, yen, yuan to pad out retail stores' end-of-the-year cash balances. Just look at the moral of the movie--is it "love thy brother?" Hell, no; it's "gift-giving is important, even if one has to force a thousand little callused hands to work all night (and are they being paid overtime?), send a traditional winter conveyance with no aerodynamically viable means of motive force whizzing all over the world blind to do it." Everyone must have a gift by Christmas morning (note the emphasis on a deadline; cash on hand, in financial terms, is always more valuable than cash promised); otherwise, Santa's shop will be deemed a failure, and closed down (ironic, considering Santa is probably the biggest, most blatant symbol of capitalism this side of McDonald's and Disney).

It's not as if the birth of Christ, which all this is allegedly about, is all that important, at least not on the Catholic calendar. Far as they're concerned, the start of the Yuletide season three weeks before Christmas (at American shopping malls the season starts after Thanksgiving; at Filipino malls it starts on the "ber" months--September, October, November) is merely the start of the Liturgical Year; it's almost incidental that this also happens to be the birth of the Church's main protagonist (and not even the actual, historical birth--that probably happened around springtime). The year's true climax, theologically speaking, is Easter, when said protagonist's mission is fulfilled ("It is accomplished!" he says in the Gospel of John).

But none of this is news, of course. I suppose I’m being tiresome, pointing out how the commemoration of a simple birth in a Middle-Eastern country (and isn't it ironic that the attention of the world is back again on that region, after all is said and done?) has grown all out of proportion into this monstrous carcass of temple-priest commercialism, bloated with gas, heaving with maggots, just stuffed full of holiday goodness and cheer. I leave you with this simple thought: rotted corpses burst, eventually, and those closest to the body, feeding on its long-dead flesh, will be inundated. You have been warned.

Signed

The Grinch.

(First Published in Businessworld, 11/30/07)

Sunday, December 02, 2007

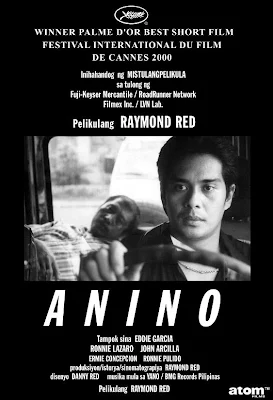

Raymond Red

The Man with the Golden Palm

Earlier this week all the newspaper articles came out about a Filipino winning an award at the Cannes International Film Festival. And not just any award; he had bagged the Golden Palm, the highest honor the festival can bestow.

Thursday, November 29, 2007

Hitman (Xavier Gens, 2007)

Snore, snore, bang, bang

Dear Messrs. Askarieh, Besson, and Gens;

Congratulations on your new film Hitman (2007); it's very handsomely made, and it looks great--you can see every quart of arterial blood and every fleck of brain matter fly across the room and spatter on the faces of all concerned (that's how it is in real life, you know). I love how the bullets make holes in people's heads, like a pumpkin being smashed (compliments to the sound effects crew for the way they capture not only the sound of spraying blood, but the stickiness of it--the way the droplets splash across the skin, slowly expand, stick there (all suggested by sound!)). And I love how, in that scene with Belicoff's brother, you had my character spot the fact that every gun on that table is fake--I agree with you, if that was really me, I would have seen that right off. You've totally captured every element in my life, exactly the way I live it; except for a few details here and there, I might even call this a documentary, or at least a docudrama. Every shot, every explosion has the ring of undeniable truth.

The man playing me, Timothy Olyphant, is quite good, if not quite as handsome; he captures my complete and utter determination not to show even a trace or suggestion of emotion. In our training, of course, we're given numbers instead of names (hence my number: '47'); more, we're taught to ignore any and all matters irrelevant to our training: fear, affection, anger, passion, humor. Even the one joke I make--what was that again? Oh yes--"I have a gag for annoying little girls." Did that joke seem lame, a limping target for my traveling companion to effortlessly shoot down? Yes, but that doesn't matter. We are not trained to tell jokes; if forced, we will improvise, but only if forced. Saying something actually interesting, much less funny, is irrelevant.

Perhaps the only scene I disliked is where that annoying little girl (Olga Kurylenko) climbed on top of my character in bed. The insolence of that girl, trying to arouse me! And her lines--did she sleep with the writer, to be given all kinds of "funny" replies to my questions? That scene is what I think people are supposed to take as comical, and I don't appreciate that. It is better off cut, and I urge you gentlemen to have it removed from the picture. It should be dipped in gasoline and lit on fire; it should be sliced into inch-long pieces, dropped in a blender, and shredded. Is my dislike for the scene irrational? I don't think so--it makes me look like a fool.

I remember little girls like her; I despise them, with their soft curves and pouting lips and huge eyes and needy whine; they are more trouble than they are worth. I like hard things, smooth and unfeeling things; why do you think I'm more eager to insert my finger into a trigger guard than I am into nasty little girls?

Perhaps the worse thing about the picture is the suggestion that I actually came to care for her. Me? The best in the business, with an all-time high body count, caring for someone so weak and contemptible? The picture is so close to being a masterpiece, gentlemen, it's so close to being an honest and undistorted account in the life of an actual hitman, it's a pity that you don't make it completely honest, completely undistorted. Little flaws, gentlemen, but the effect they have on me! I almost want to line you all up in a row, handcuffed to your chairs, myself with an automatic pistol in hand standing before you…

Apologies; that was uncalled for. I'd like to point out that the action is largely well done, only Mr. Gens cuts too often in the close combat sequences to see my blocks and strikes clearly, not to mention my stances (Balance, as anyone well versed in the martial arts knows, is all; and balance always comes from a good stance, good footwork. An action filmmaker who gives due attention to the fighters' footwork is an action filmmaker who knows what he's doing). I love it that they give due emphasis to the different countries in which I have operated in the past--Turkey, Russia, those little dictatorships in Africa (But wait--no China, Vietnam, the Philippines? Didn't the budget allow for it?).

As for the rest of the cast, I congratulate them all; they died handsomely. It's as if their faces and bodies were blank canvases against which I can wield my paintbrush, creating masterpieces. I like to think that, humble skill that I possess, I do have something of the creative spirit in me; I like to think that somehow, in some way, I can be considered an artist.

Of my co-stars, I would especially like to single out Mr. Dougray Scott as Mr. Whittier, the Interpol officer assigned to arrest me. Mr. Scott is a fine actor, and a wonderful boon companion; I would have much rather spent more screen time in his presence, with his warm eyes and soft hands that look at me so intensely (and believe me, I return the gaze!), than I do with that irritating hussy. I remember insisting that you gentlemen write in some kind of wrestling scene between me and Mr. Scott; I find it strange that you would be so unenthusiastic about that--I'm sure it wouldn't have hurt the boxoffice any.

Still--details, details! This production is, due respect to Mr. Besson aside, much preferable I think to his Leon (1994) with its equally implacable assassin (Jean Reno) saddled with yet another whiny little slut (I did not like the ending so much, which is redolent of what I believe is called "irony"--if I had asked for as much iron, I would have it planted firmly between my enemies' eyes). It is, I believe, much preferable to the supposedly great hitmen films of the past--Jean-Pierre Melville's Le Samourai (1967), whose body count hardly compares to mine; Akira Kurosawa's Yojimbo (1961), which is tainted too much with that even weirder element called "black comedy;" Seijun Suzuki's Koroshi no rakuin (Branded to Kill 1967) and Pisutoru opera (Pistol Opera 2001) which frankly I just didn't understand. No, this picture is all too easy to understand--loud, wet, uncomplicated, boasting of an astronomical body count. My congratulations to all--I predict it will make millions!

Your humble servant:

47

(First published in Businessworld, 11.23.07)

Dear Messrs. Askarieh, Besson, and Gens;

Congratulations on your new film Hitman (2007); it's very handsomely made, and it looks great--you can see every quart of arterial blood and every fleck of brain matter fly across the room and spatter on the faces of all concerned (that's how it is in real life, you know). I love how the bullets make holes in people's heads, like a pumpkin being smashed (compliments to the sound effects crew for the way they capture not only the sound of spraying blood, but the stickiness of it--the way the droplets splash across the skin, slowly expand, stick there (all suggested by sound!)). And I love how, in that scene with Belicoff's brother, you had my character spot the fact that every gun on that table is fake--I agree with you, if that was really me, I would have seen that right off. You've totally captured every element in my life, exactly the way I live it; except for a few details here and there, I might even call this a documentary, or at least a docudrama. Every shot, every explosion has the ring of undeniable truth.

The man playing me, Timothy Olyphant, is quite good, if not quite as handsome; he captures my complete and utter determination not to show even a trace or suggestion of emotion. In our training, of course, we're given numbers instead of names (hence my number: '47'); more, we're taught to ignore any and all matters irrelevant to our training: fear, affection, anger, passion, humor. Even the one joke I make--what was that again? Oh yes--"I have a gag for annoying little girls." Did that joke seem lame, a limping target for my traveling companion to effortlessly shoot down? Yes, but that doesn't matter. We are not trained to tell jokes; if forced, we will improvise, but only if forced. Saying something actually interesting, much less funny, is irrelevant.

Perhaps the only scene I disliked is where that annoying little girl (Olga Kurylenko) climbed on top of my character in bed. The insolence of that girl, trying to arouse me! And her lines--did she sleep with the writer, to be given all kinds of "funny" replies to my questions? That scene is what I think people are supposed to take as comical, and I don't appreciate that. It is better off cut, and I urge you gentlemen to have it removed from the picture. It should be dipped in gasoline and lit on fire; it should be sliced into inch-long pieces, dropped in a blender, and shredded. Is my dislike for the scene irrational? I don't think so--it makes me look like a fool.

I remember little girls like her; I despise them, with their soft curves and pouting lips and huge eyes and needy whine; they are more trouble than they are worth. I like hard things, smooth and unfeeling things; why do you think I'm more eager to insert my finger into a trigger guard than I am into nasty little girls?

Perhaps the worse thing about the picture is the suggestion that I actually came to care for her. Me? The best in the business, with an all-time high body count, caring for someone so weak and contemptible? The picture is so close to being a masterpiece, gentlemen, it's so close to being an honest and undistorted account in the life of an actual hitman, it's a pity that you don't make it completely honest, completely undistorted. Little flaws, gentlemen, but the effect they have on me! I almost want to line you all up in a row, handcuffed to your chairs, myself with an automatic pistol in hand standing before you…

Apologies; that was uncalled for. I'd like to point out that the action is largely well done, only Mr. Gens cuts too often in the close combat sequences to see my blocks and strikes clearly, not to mention my stances (Balance, as anyone well versed in the martial arts knows, is all; and balance always comes from a good stance, good footwork. An action filmmaker who gives due attention to the fighters' footwork is an action filmmaker who knows what he's doing). I love it that they give due emphasis to the different countries in which I have operated in the past--Turkey, Russia, those little dictatorships in Africa (But wait--no China, Vietnam, the Philippines? Didn't the budget allow for it?).