Don't have a perfect system for choosing, don't pretend to have one; basically I try pick whatever had some kind of commercial release in the USA; that, or if they had a release in the Philippines, and I failed to include them the previous year (plenty of those). Or I feel I can actually include them in a 2010 list because they have yet to have (nor will they probably ever have) a commercial release, and I want to acknowledge them anyway. I try to err on the side of inclusiveness.

As for what constitutes "best" as opposed to "notable," purely gut feel, as in: I roll the title down my tongue, and if my gut tingles with similar or greater excitement at the mere sound of the words, it's in; otherwise, it's out. That's why Social Network, which I liked a lot when I first saw it, is relegated to the "notables." Others I like too much but are too otherwise flawed to include in "best."

Which is probably all bull, of course. Look up the titles, read my articles if you like, see if you agree or disagree. I find this more useful than having some half-assed committee sit down and tabulate a vote--as if two minds can actually agree on something valid and worthwhile. And as for all that statistical jazz--averaging out, grade curves, lopping off extreme values, I quote Mark Twain: "there are lies, damned lies, and statistics" and misquote Chairman Mao: "let a thousand best-of lists bloom!"

The best of the year:

The Fighter - how does it shape up against other recent fight movies? It's different enough to be worth watching, with its video footage and edgy editing, and that's plenty enough in my book.

The Fighter - how does it shape up against other recent fight movies? It's different enough to be worth watching, with its video footage and edgy editing, and that's plenty enough in my book.

Forbidden Door - One of the better horror films in recent years...and not a silly swan in sight!

The Girl on the Train - Think John Hughes only sophisticated, and possessed of subtler storytelling instincts.

The Imaginarium of Dr. Parnassus - a relatively normal (?) Gilliam film, about the doctor and the Devil and a really nasty customer.

Mary and Max - Two friends an ocean and a continent away, talking to each other through the postal mail. One of the saddest and loveliest-looking animated films in recent years.

Ang Ninanais (Refrains Happen like Revolutions in a Song) - John Torres' attempt at mythmaking is erotic, funny, and like nothing you've ever seen before

Ang Paglilitis ni Andres Bonifacio (The Trial of Andres Bonifacio) - Mario O'Hara's take on the other great Filipino hero is understated drama, anguished tragedy, a tremendous love story, and in my opinion the film of the year.

A Prophet - The Godfather in French, and in the claustrophobic confines of prison. The coming of age of a young crime lord, and what's so chilling about the story is that he's only too ready to take up the reins of power.

The Secret of Kells - the other great animated feature of recent years, an unflinching celebration of Celtic imagery.

- Tom Ford's debut film is visually gorgeous and dramatically compelling, about a gay man who has just lost the love of his life.

Shutter Island - Leonardo DiCaprio's other (and in my book, far better) nightmare trip, a descent into schizophrenic states of paranoia as only Scorsese can conceive.

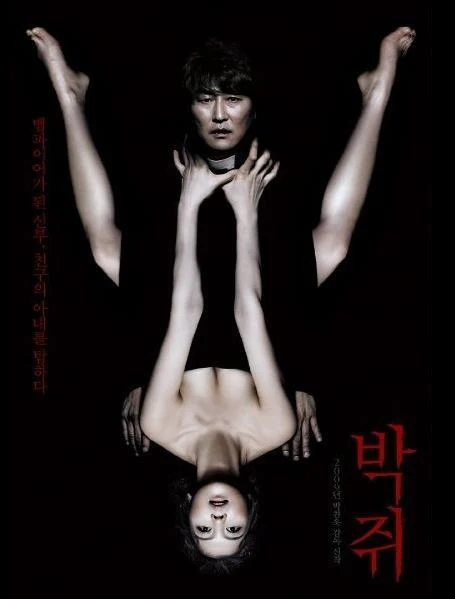

Thirst - In a year full of bloodsuckers, the one vampire film that really transgresses, and the first Park Chan Wook film I really like.

Vengeance (Johnny To) - Basically Christopher Nolan's Memento, only done by a real filmmaker. The plot--a Parisian chef seeking revenge for the death of his daughter's family--is an excuse for extravagant gunfights and thriller sequences as only To--arguably the consistently finest filmmaker working now in Hong Kong--can do em.

Of course you have grand opera slow-motion; of course you have balletic gunslinging; of course you have casually funny sequences of male camaraderie--with Woo you might wonder at the homoeroticism, with To you get the genuine vibe of a bunch of boys hanging out and fooling around (what makes To so moving is that his heroes are often overgrown boys, living up to and enforcing an often fatal code of honor). An example: when it's time to move into action, Anthony Wong tosses a peanut at Suet Lam's face; Lam picks the nut off his cheek and without much forethought pops it in his mouth. Lovely.

Of course you have grand opera slow-motion; of course you have balletic gunslinging; of course you have casually funny sequences of male camaraderie--with Woo you might wonder at the homoeroticism, with To you get the genuine vibe of a bunch of boys hanging out and fooling around (what makes To so moving is that his heroes are often overgrown boys, living up to and enforcing an often fatal code of honor). An example: when it's time to move into action, Anthony Wong tosses a peanut at Suet Lam's face; Lam picks the nut off his cheek and without much forethought pops it in his mouth. Lovely.

The White Ribbon - along with Park Chan Wook the other enfant terrible of World Cinema at his most magisterially measured.

The flawed but interesting, or otherwise notables:

Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs - Mostly harmless. But there aren't enough movies about food out there, much less animated movies about food.

Despicable Me - Plays well to your inner bad guy. Mostly funny, minimum sentiment.

Despicable Me - Plays well to your inner bad guy. Mostly funny, minimum sentiment.

Himpapawid - Raymond Red's first feature in years is the tragicomic story (partly true) of a man who wishes to fly.

How to Train your Dragon - Yet another animated picture not Pixar that seems to offer something other than the standard Pixar uplift. Including Jay Baruchel with a voice performance that evokes a teen Woody Allen.

The Hurt Locker - won over ex-hubby's overproduced CGI epic, which is no big feat, but nevertheless a compelling psycho drama, possibly the best yet on the Iraq war.

Invictus - Eastwood's tribute to the Obama administration (at least that's how I read it), and a compelling rendition of an interesting footnote in world history.

The Killer Inside Me - Winterbottom's graphically faithful rendition is too literal, yet there are touches that make it worthwhile.

The King's Speech - The testosterone version of Pygmalion, My Fair Lady, or Educating Rita leaves us with the image of two men in a room, struggling for domination, and reassurance, and human contact.

Last Supper No. 3 - The Philippines first legitimate legal comedy.

Let Me In - Not a bad remake. Not as good as the original, but it honors its source.

Machete - Avatar reeks like a potful of fermented Smurfs; Inception seizes up like a constipated large intestine; Machete is the action movie of the year. It has balls, it has breasts, it has sweat, it has blood, it has style, it has humor, it has a heart as big as all of Mexico.

Unlike Cameron, Rodriguez has a sense of irony about himself; unlike Cameron he feels the Big Message (illegal immigration and racism) in his bones. Unlike Nolan, Rodriguez can actually do an action sequence; this may be his best work yet. It's easily his most consistently sustained.

My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done? - oddly subdued collaboration between Werner Herzog and David Lynch that, thanks to its precisely slanted view on life, oddly stays in the mind long after the credits roll. Indelible images include a vivid no-budget staging of The Eumenides, of a basketball caught in the branches of a sapling, and God coming out of a garage door and rolling down a driveway.

Machete - Avatar reeks like a potful of fermented Smurfs; Inception seizes up like a constipated large intestine; Machete is the action movie of the year. It has balls, it has breasts, it has sweat, it has blood, it has style, it has humor, it has a heart as big as all of Mexico.

Unlike Cameron, Rodriguez has a sense of irony about himself; unlike Cameron he feels the Big Message (illegal immigration and racism) in his bones. Unlike Nolan, Rodriguez can actually do an action sequence; this may be his best work yet. It's easily his most consistently sustained.

My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done? - oddly subdued collaboration between Werner Herzog and David Lynch that, thanks to its precisely slanted view on life, oddly stays in the mind long after the credits roll. Indelible images include a vivid no-budget staging of The Eumenides, of a basketball caught in the branches of a sapling, and God coming out of a garage door and rolling down a driveway.

Salt - Old-school action filmmaking (circa '80s) at its best.

Scott Pilgrim vs. the World - Let me put it this way: Edgar Wright made me like my first video game movie. Small miracle.

The Social Network - Fincher's epic dramatization of an online phenomena fits into his gallery of lonely protagonists obsessed with the eternal.

Survival of the Dead - George Romero as the ultimate termite artist, doing straight-to-video installments of his legendary Dead series.

The Tourist - Hitchcock redux, yes, but in this day and age of in-your-face action and even louder romantic comedies, secondhand Hitchcock is better than no Hitchcock at all.

The Town - not quite as precise as Heat, not as funny or intense as The Departed, what Affleck's film does have is an ineffable sense of place and time.

Up in the Air - Imagine that, a comedy about unemployment. Best portions are the actual interviews of laid-off workers.

Voyage of the Dawn Treader - Arrives at a point when the Narnia series starts to become really interesting. Special effects are second-rate, but Michael Apted's direction keeps the emotions and relationships clear, as they should be.

Where the Wild Things Are - Not as good as Sendak's twenty-page original, but as its own creature it's not bad.