Sleeping

beautifully, too

Catherine

Breillat's The Sleeping Beauty is her version of the Charles Perrault fairy tale, a radically different but no less fascinating

take from Julia Leigh's 2011 debut feature of the same name.

Her

tale begins literally at the beginning, with the child Anastasia's

umbilical cord cut by the evil fairy. The three good fairies

come running after; “we lost track of time,” they offer by way of

explanation. “You're scatterbrained,” the evil fairy informs

them. By way of amends, the good fairies attempt to offset the evil

fairy's curse with their own spells. “The princess won't

die--she'll just fall asleep for a hundred years,” offers one; “I

can make the princess wander in her sleep,” offers another; “I

can make her pierce her hand when she's six and wake up a hundred

years later age sixteen.” When they look at her like she's an

idiot, she explains thusly: “childhood takes too long.” Julia

Leigh's version isn't straightforward funny like this one--its humor

is more deadpan surreal--but Breillat's wears its fizziness on its

sleeve, saving the fangs and poisoned thorns for later.

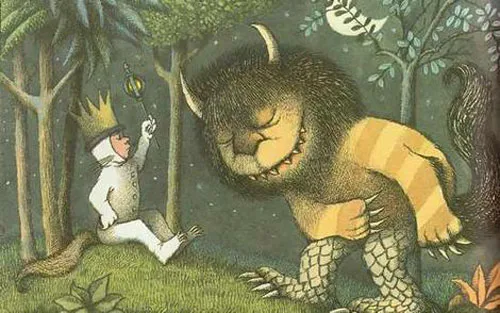

The

resulting child is not, to put it mildly, quite that normal.

Anastasia (the enchantingly willful Carla Besnainou) calls herself

'Vladimir' and declares herself a tomboy; one wonders at the Slavic

names, the tree-climbing, the language (mother speaks to grandmother

in subtitled Russian)--are they alluding to Tchaikovsky's ballet? The

Romanovs' mysterious daughter, who also had a penchant for

tree-climbing? When her hand is wounded at age six she is transported

(past a giant covered with boils) from the early 19th

century to what looks like modern day, complete with contemporary

trains and houses. She stays with kind-hearted Peter (Kerian Mayan)

and his mother, and for a time lives a fairly happy life--when Peter

shows her a queen bee too fat with royal jelly to move, she cries,

afraid to be (like the bee) a prisoner of her own weight; Peter hugs

and promises to protect her.

As

with any fairy tale, matters can only remain happy at tale's end, not

its middle; A splinter of ice presumably from the Snow Queen (Romane Portail,

imperious in her furs and gemstone-encrusted breast) lands on Peter's

eye, causing him to see all things as ugly, all people as grotesque;

he insults his mother, and drives Anastasia to tears, repeatedly.

Peter's mother has a different explanation for what's happening,

though no less truthful: “You're at that awkward age (We later

see Anastasia reading from a textbook the definition of puberty)!"

From Perrault's tale Breillat has shifted gears to tell a more

modern, more nakedly emotional one--Hans Christian Andersen's “The Snow Queen.” Peter climbs into the Queen's sled, which takes him

away; Anastasia leaves home (she seems to have largely forgotten her

royal origins) to look for him.

Additional

adventures, each more picaresque and colorful than the last--a train

station managed by a dwarf and a mannequin; an albino prince and

princess, eating rainbow meringue; a trip across snowy wastelands on

a sled pulled by a reindeer, the sky lit by curtains of green light;

a robber princess (Luna Charpentier), about the same age as

Anastasia, as eager to slit her throat as play with her. Anastasia's adventures, we come

to realize, have been defined by the women at the film's

beginning--the evil fairy with her curse; the first good fairy with

her sleep spell; the second with her qualification that the sleep be

filled with dreams (and what dreams!). You can pretty much define a

fairy tale from all the conditions imposed: conflict (the curse),

contrivance (sleep instead of death, dreams instead of just sleep).

As for the third--

The

third's spell reveals to us the final element of a bona-fide fairy

tale--it must have an end. Anastasia (the awkwardly beautiful Julia

Artamonov), now sixteen, comes crashing down in the twenty-first

century. Doesn't seem like one at first (like a crash, I mean); first

she meets Johan (David Chausse), Peter's great-grandson, and with the

castle she has slept in for a hundred years as backdrop they flirt. He makes for a wonderful partner, playful and

patient and gentle; she in turn is an ardent student, hungry to

learn. Later, she has a reunion with her robber-princess friend (now

played by Rhizlaine El Cohen), and the robber-princess is the first (not Johan) to

initiate Anastasia into the mysteries of carnal pleasure.

Then--listless

orgies, violent quarrels, ennui, nihilism, despair. The film pretty

much ends up like a--well, like a regular Breillat film, complete

with torn fishnet stockings. Breillat's cheerfully vigorous

fairy-tale of a film wakes up to the grim reality of modern-day

France, magic wands and pixie dust all gone.

How does this compare with Leigh's later version? Emily Browning is breathtakingly beautiful, but Artamonov has a firmer hold on your sympathies, as you've followed her adventures since childhood. Aside from the humor, which this film wears more nakedly on its sleeve, and the eroticism, which has a lovely fairy-tale aura, Breillat's take is more forthright with its ideas, more openly playful with them; Leigh's version is an exquisitely carved cameo that you gaze at, fascinated, trying to winkle out its mysteries. Leigh's take on men is equally ambivalent, if not a little sympathetic; Breillat, like a child, sets you straight about them--they're not to be trusted. Seek the arms of another woman first, if you must seek knowledge and experience.

No wonder audiences for

this film were so angry, critics especially: Breillat for the

umpteenth time has refused to play by anyone's rules, meet anyone's

expectations, kneel down or bend over for anyone's viewing pleasure.

Talk about a Grimm fairy tale, this one captures the brothers' unflinchingly violent, folksily humorous, casually fabulist tone.

First published in Businessworld, 5.17.12