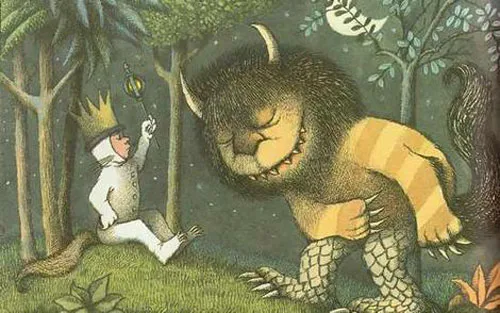

Max with my favorite wild thing (who shall forever remain nameless, as he should)

(Re-posting as a tribute to the late Maurice Sendak 1928 - 2012)

Mild thing

The best parts of Spike Jonze's Where the Wild Things Are (2009) are possibly the scenes depicting Max's home life--Jonze takes camera in hand and follows Max up and down stairs, through hallways, into an improvised snow fort to capture the casual lyricism of everyday life (Jonze set it in wintertime presumably because he needed the added melancholic touch, to cut through whatever sticky pathos might be found in the script). When adolescent youths unthinkingly destroy the fort, trapping Max inside and subjecting him to a vividly realized moment of claustrophobia (Edgar Allan Poe would appreciate this) Max finds himself weeping angry tears. When his mother (the lovely if--for this production--more domesticated Catherine Keener) pays more attention to her new boyfriend (Mark Ruffalo) than him he finally turns wild, screaming and biting his mother, who yells at him--a startling moment reflected in Max's startled expression, and in his even more startling response: to run out of the house into the snowy winter night, board a sailboat, and set off to unknown realms.

All well and good for a preteen angst picture. But this is an altered Max, a thoroughly re-tinkered Max, considerably less funny and with less of a crack comic timing than Sendak's creation. Sendak's Max was a truly terrible thing, no less so for the fact that his wildness was sui generis--unexplored and unexplained. He chased the poor family dog with a dinner fork (anticipating his fellow Things' famous catchphrase “I'M GOING TO EAT YOU UP!”) and “got up to” one bit of mischief after another till his mother called him “Wild Thing!” and sent him to bed without supper. The punchline--Max throws the door (you can imagine it slamming shut just seconds before) a hurt expression, as if he had expected praise, not punishment, for his behavior.

And then the most magical moment in the book--there's no near equivalent in the movie, and Jonze unwisely (or is it wisely?) does not even make an attempt--huge leaves and giant jungle blooms sprout in Max's bedroom; the four posts of his bed turn into trees, the carpet into tall grasses, the ceiling into a thick woven canopy. Every time I read this--at four, fourteen, even at forty--I read with wide eyes, wondering if, should I close my eyes, my room might undergo a similar transformation (it never does, but I never tire of wondering).

Max arrives at some strange island / strange land, washing ashore in an elaborate (if somewhat unnecessary) landing sequence; he climbs up a cliff, enters a forest. When Max and the Things meet, it's a fairly unconvincing encounter: the Things surround him (silent, expectant, threatening) and Max looks up (wet, shivering) to claim in a tremulous voice that he's “a great king, with magical powers.” All the Things stare at Max doubtfully; they seem to be expecting him to throw them a line, as if they had all lost their places in the script. Sendak's Max betrayed no such weakness; he had charisma to spare and solved the problem easily by staring at them without blinking until they capitulated and declared him the Wildest Thing of All.

At this point Jonze's movie departs from Sendak's book to weave a tale of estranged friendships, growing mistrust, painful regrets. Just in time, too--the book simply (and confidently) relied on Sendak's inimitable artwork to depict the Wild Rumpus that follows, images of unbridled joy and ferocity (Max at one memorable point in the revelry giggles as if it were all some private joke) that go on and on until Max grows tired, boards his boat and sails back home, the last line in the book bringing the entire story to a full circle.

Jonze gives the Wild Things names--K.W. (voiced by Lauren Ambrose), she with the stringy hair; Ira (Forest Whittaker), with the faintly anthropoid body; Judith (Catherine O'Hara), with the horned nose; Carol (James Gandolfini, aptly cast) with the fiery temper, striped chest, fish-scaled legs (my favorite Thing, though I suppose he was everyone's favorite--he's given the most substantial role). Not sure I'm happy with the names; I've known them as nameless all my life, and have always imagined that if we met, we would never bother with talk--just roar, charge at each other and either roll playfully on the ground wrestling or eat the other up.

Carol (as mentioned) has anger issues; he is both the warmest and most dangerous of the Things. Max sees him as a good friend, and--implicitly--the missing father figure in his life (Can a father act childishly and throw tantrums? Absolutely). K.W. is more of a mother figure who comforts Max and, at one point, hides him in her womb (need to see it to believe it--works, too) when an angry Carol comes looking for him. The story comes to a crisis, Max again boards a boat to sail home, trailing behind him Wild Things that want to eat him up, only this time the emotions--as is typical in a Jonze film--are sadder, more complex. Not necessarily better--Sendak's narrative flows in a clear, swiftly flowing stream, which serves to hide undercurrents of anger, fear, frustration; what Sendak buries in a furiously paced avalanche of verbal and visual delights Jonze makes explicit, somewhat plodding, less intensely flavored.

Jonze's film works best when it departs completely from Sendak and, like Max, strikes out on its own. He paints an altogether moodier world, populated by creatures with wide (if toothy) smiles and bulging eyes that imply (Carol in particular) soulful depth behind them. But while critics talk of the Wild Things with their puppet limbs and digitally crafted faces, I was more fascinated by the sets designed by K.K. Barrett: seemingly woven out of sticks and vines and branches (inspired, Barrett says in an interview, by Sendak's crosshatching style), the Things' homes take shape as either egglike shelters that you can pick up and toss about (just imagine--mobile homes!), or as a fort that resembles a gigantic snail with a pair of eyestalks soaring into the sky. Then there's the miniature city carved by Carol, complete with an elaborate canal system; Carol pours a bucket of water into the city's channels and drops in a tiny boat with two people riding inside--they wander the waterways like Huck Finn and friend, out to see the world on a little canoe. As an adaptation of Sendak, I think the movie is a failure--you simply cannot adapt perfection--but as a boy's dream (or rather, Jonze's dream of a boy's dream) of his inner demons confronting then sitting down to sadly acknowledge the presence of the other, perhaps even learn to care for the other, the picture is worth seeing.

First published in Businessworld, 2.4.10

No comments:

Post a Comment