(Warning: story discussed in close detail)

It's been fifty years--half a century--since Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho first screened in theaters, and for the occasion there are plenty of articles written for the occasion. Jack Sullivan in the Wall Street Journal insists that Bernard Herrmann's slashing music score not only enhanced the infamous shower scene, but saved the film; J. Hoberman sketches the historical context in which the film appeared (it was released in roughly the same period as Federico Fellini's 8 1/2, Michael Powell's Peeping Tom, Michelangelo Antonioni's L'Avventura), then reprints in whole Andrew Sarris' then freshly-minted appreciation:

“Psycho should be seen at least three times by any discerning film-goer, the first time for the sheer terror of the experience...the second time for the macabre comedy inherent in the conception of the film; and the third for all the hidden meanings and symbols lurking beneath the surface...”

But what keeps Hitchcock's movie in the mind? Mind you, I don't think it's his best--it doesn't have the doomed intensity of Vertigo, the apocalyptic metaphysics of The Birds--but does persist in one's memory, somehow unsettle one's emotional equanimity no matter how at peace one is with the world.

I can't say the power resides in its the infamous shower scene, at least not any more. The scene remains admirable for the way Hitchcock manages to keep the action coherent despite the swift editing (over seventy different shots in forty-five seconds), and it's remarkable how much panic is induced by Bernard Herrmann's music (people have likened the score to the screeching of birds, and insist Herrmann must have electronically incorporated their cries (he didn't; it's composed entirely from shrieking violins)). But we have watched that scene through countless imitations, parodies, homages, youtube excerpts, and its every shot, cut and scream has become painfully overfamiliar, a cadaver left out in the open for far too long.

Sullivan writes that Hitchcock never intended that scene to be scored, that Herrmann in fact wrote music for it without Hitchcock's permission. The sequence needs music, I submit; it is too fragmented, too formally radical (Seventy-plus shots! Forty-five seconds!) to be accepted by the general public without accompaniment. Music pulls those discrete shots together, takes the whole to a deeper, less reasoned level (another theory has it that Herrmann was inspired by marmosets, whose shrill cries of animal terror sound remarkably like Herrmann's violins). A heavily edited sequence usually works best with music, a principle Herrmann realized despite Hitchcock's intentions.

Contrast this with Hitchcock's attempt some six years later to top himself in Torn Curtain, where a man is slowly murdered. The sequence follows the man's painful progress around the room to the gas oven, the only aural accompaniment being his and his killers' groans, the eventual hiss of the oven. This works, I submit, because the murder is presented with less stylized fragmentation--fewer quick cuts requiring the scraping of loud violins to bind it, emulsify it. In the context of today's fashionable preference for hand-held camerawork, rapid-fire editing and amplified symphonic stereo (loud music to kill to!), it is if anything even more disturbing--the desperate silence, the impassive, unflinching gaze of the camera as the man's hands slowly relax their grip on life.

That said, there are a pair of shots in Psycho's shower scene that retain much of their power--the zoom into blood and water spinning down the shower drain dissolves into a slow spiral pulling out of Marion Crane's lifeless eye. Certainly (as someone put it) this refers to the spiraling camera moves that describe much of Vertigo, but here it's also as succinct and final a summation of the loss of a human life--the sum total of Marion's dreams and fears and hope for redemption, dribbling away.

There is Arbogast's dreamlike climb up the stairs, as if the stairs were not quite there (they weren't, at least not in the subsequent fall; Hitchcock used rear projection). There is Lila's desperate yet silent search of Mrs. Bates' and Norman's room (the book she picks up and opens--Robert Bloch in his novel mentions a 'pornographic image,' but Hitchcock's deft cut from book to Marion's face suggests something bizarre, yet not flinch-inducingly repulsive. Just what did she see? the viewer wonders). There's Marion's descent to the fruit cellar and timid approach towards Norman's mother (“Mrs. Bates?”)--basically any and all scenes of atmosphere and mounting dread. Remembered for the way he fractured time and space in the shower stall, the Hitchcock I remember best unified time and space, often by means of a single shot.

But to talk about shots and cuts, scenes and music, shower stalls and knives is to talk only about the props and décor of horror, not of its essence. The haunting, horrifying heart of this haunting, horrifying movie? Why dinner, of course--that simple scene of Norman talking to Marion while she takes her supper.

It starts out coyly. Marion, having overheard Mrs. Bates humiliate Norman over her (“Go tell her she'll not be appeasing her ugly appetite with my food, or my son!”) pushes her door ajar and invites Norman and his tray of food into her room; Norman with his boyish shyness hesitates. “It might be nicer--and warmer--in the office,” he says. In the office he tells her: “Eating in an office is just too officious. I have a parlor back here.”

Inside the parlor the teasing fall of veils continues, with Norman and Marion trading confidences under the gaze of impassive birds (who do those birds represent--Mrs. Bates? Norman's other girls? The forbidding, disapproving, predatory world outside?). At one point Norman speaks sharply, bitterly; at another Marion drops her guard and lets slip her true name and destination.

Here is the true horror: two people have made a connection, glimpsed inside each others' worlds, recognized the pain and loneliness in the other, grown to care for one another. The rest of the world proceeds to destroy that connection, trivialize it, ultimately serve it up as fodder for a psychiatrist's explanation, as remains to be found in a car trunk, pulled out of muck by a steel chain.

Horror has made great strides since this film; improved its makeup techniques, prosthetics, developed digital effects to the point that one can show a man's head being sliced in half and the man still moves around, realistically jerking and bleeding for minutes before he falls over. This is basically pizza making in my book--you roll out a disc of dough, spread tomato sauce, sprinkle toppings, call it food. Likewise with movies--you roll out a mannequin, squirt tomato sauce, sprinkle guts and prosthetics, call it horror (maybe enhance the experience digitally with 3-D). An extremely limited--and limiting--sensibility.

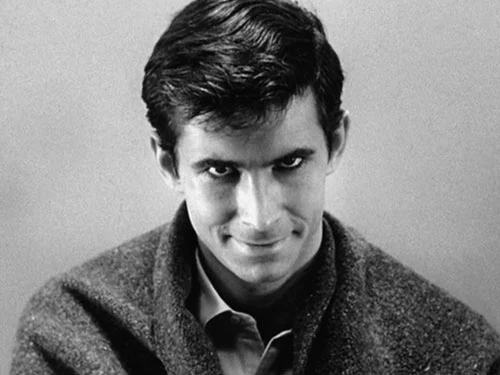

Hitchcock's final shot isn't just a reminder that there are things in heaven and earth beyond explanation, it's a reminder of what's gone. You see Norman's fragile handsome face, the shy charm from that long-ago supper sparkling briefly; then he smiles, the smile cross-fading with the rictus grin of Mrs. Bates, and she is utterly irredeemably insane.

First published in Businessworld, 7.1.10

11 comments:

I saw it just once five years ago and the bit that remains most is the girl driving away with the money, to the accompaniment of heart throbbing music. Money is a complex thing, and the stolen dollars occupy a central position, the point where Norman's and Marion's worlds intersect.

I agree the money occupies a central position, though I don't think it has anything to do with anything in Norman's world--other than that it drove Marion into that world.

From Ted Fontenot:

"That's a nice analysis, Noel. Really good. Besides the detailed technical survey, I like your comment about the movie destroying one’s equanimity no matter how at peace with the world one might be.

I tried posting this comment on your blog, but keep being rejected: error bX-8fawa0, whatever that is. Anyway, just wanted to let you know how much I enjoyed it.

I think that the true terror this movie evokes, what is shocking and hyper-frightening, is the sudden palpable sense that the viewer is shocked into about how the irrational can suddenly impinge on the ordered and rational. It’s like a day at the beach with the wife and kids, you happen to look up, and there’s this monstrous tsunami coming at you. The movie is like a force of nature. Marion (by the way, I think you referred to "Lila" investigating in the house as "Marion") has learned her lesson. She's going back; she's going to make restitution. That should mean something. She’s essentially a good, moral, ethical person. It counts for nothing.

Hitchcock here, as in Vertigo, is after bigger fish to fry than the psychological. Psycho, like Vertigo, is about the philosophical. Morality doesn't matter. Marion like Scottie in Vertigo doesn’t meet the definition of the classic tragic figure. (Well, maybe Marion does a little, for a moment.) Scottie’s tragedy is he wants what he can’t have—what doesn’t exist even. Marion’s is even more absurd. What's shocking about Psycho isn't that the main character, up to then, is so suddenly summarily dispatched, it's that the universe has no pity for her, this good and nice person who will, after all, do the right thing. What I’ve always found as also shocking was how Norman in cleaning up after his mother folds up the “stuff” and buries it along with Marion. It means nothing. It’s the McGuffin. It could have been almost anything else that could have become a “portal” to the terror of the totally irrational. Not only that, what makes it even more horrible is when you realize that she’s done in by someone who is also really a pretty nice and decent person (except for being an insane killer). Like Vertigo, it’s an account of the zeroing out of the sense of a moral. You know that stuff about good/evil, light/dark, kind/cruel (name your duality)--it don't mean shit: this is how things are. Random horror can strike at any time. It’s really a new aesthetic sensibility that Hitchcock through his career wend his way to the result he did through an evolutionary process whose mill ground as exceedingly fine, and as cold and pitiless and inevitable, as Darwin’s. I don’t think Hitchcock deliberately and consciously calculated this out by the numbers. He may not even have kenned how radical his sensibilities had become by the time of Vertigo. From his struggles with an imposed Catholic (Christian) moral paradigm, he finally shrugged it off like a snake molting its skin to enter into a freeing and terrible Darwinian aesthetic. I, for one, would really like to read and hear what scholars and critics like Denis Dutton would have to say about this aspect of Hitchcock’s work."

Thanks! And I'll correct that Marion/Lila snafu ASAP.

Here's what I think on Catholicism: I don't think Hitchcock sloughed it off completely, and I don't think he should have. Catholicism and its concept of guilt haunts the margins of his pictures like the supernatural beings he never quite managed to put in. The moment he completely frees himself of Catholic guilt, his hangups would all resolve themselves--like pieces of an ancient puzzle falling into place, and he'd stop making movies. Which he didn't, not after Psycho anyway, and this is a good thing. I agree there's the element of cold Darwinism in this picture, but it's the view of cold Darwnism by a traditional (and, I suspect, still practicing) Catholic.

Most Catholics, incidentally, believe in Darwin's theory--I do, and I was taught in a Catholic school. We have absolutely no problem with evolution, and science. That's them Presbyterians and Babtists you're probably thinking of.

And that pitilessness, down to the 40,000 dollars, is yes I agree, shocking. More so because we're brought to care for Marion so much (the same strategy Haneke used so effectively in both versions of his Funny Games).

(From Ted again, who continues to get grief from Blogger for some reason):

Tried to post the following on your blog as a follow-up, and got the same error message:

The point I think I was trying to make clear (and I'm still groping to understand it myself) is that Psycho takes us beyond any moral universe where there is accountability. We're through the looking glass; we’re into the tragic of the absurd... Personal accountability doesn't matter. It’s irrelevant. It isn’t even quaint; it’s just not a play on the board at all. That's what's so brutal about the film, what's so radical about it, and what makes it more than the progenitor of the slasher films that would follow. That's why disposing of the money so curtly is like a slap—it’s a snap out of it slap—all that doesn’t matter. The ethical/moral sense of stealing the money and then returning makes no difference one way or another to her fate. Or his. One step more and it’s a free fall into nihilism. Hell, we might be there anyway. I used to think the psychologist explaining Norman away was both redundant and insultingly simplistic. But the cut back to Norman’s insane grin tells you what all that psycho-bullshit was: pointless. We can pretend to have worked the explanation all out. Norman’s still going to try to persuade you he wouldn’t hurt a fly. And, you know, we’re ready to buy into it. The irrational carnivore just feasts on our need to believe the lion will lie down with the lamb. The words soothe us; we ignore the toothy grin.

"8 1/2" was released in 1963. "Psycho" in 1960. J. Hoberman, indeed.

Poor phrasing. It was released in the early '60s with 8 1/2, L'Avventura and other films.

Yes, excellent analysis in the piece and the follow up discussion. It used to drive me crazy reading people's problem with the ending of the film. It's unnecessary some insisted. It is Hitchcock's BOO. It is a cop-out. That business with the fly.. c'mon. Not a shock.. jump boo (hand suddenly coming out of the grave.. DePalma style) but one that really stays with you. We've spent time with an insane person and partly because of Tony Perkins himself, felt something for him (not possible for Vince Vaughn to replicate), complicated thoughts, and then that final smile. Not evil...but insanity. For all the style throughout, an authentic sort of moment. Boo indeed.

Thanks, Chris. Good to hear that from you.

Post a Comment