I had copies of the scripts of his three classic Quatermass series: The Quatermass Experiment; Quatermass II; and the great Quatermass and the Pit. I've only seen the film versions of the first and second series. I think he's one of the greatest scriptwriters to ever work in the medium of television.

His work is full of eerie effects and shocking moments--the astronaut's arm rooting in the potted cactus; the synthetic food manufacturing plant that looks uncannily like a moon base; the laborer hopping like a grasshopper, trailing a flock of flying dishes. Yet all these images no matter how strange had rational explanations behind them (always malevolent, otherwise--what's the point?), and reason and science are always key to fighting their cause.

And at the root of these exciting series is a strong strain of sanity and humanism, something sorely lacking in Quatermass time, apparently (often as not, he's about the only one who possesses such qualities) as they are in ours.

This is what I had to say about the film version of The Quatermass Experiment:

Finally saw Hammer's The Quatermass Experiment (1955), and wow, what a hatchet job they did on Quatermass. From the voice of reason of the original BBC serials, he's become a loud, bullying American, who gets to boss everyone around just because he can raise the biggest volume. There's an interesting subtext, in that he's both the guy who creates the whole mess and the man who deals with it later (and, even later, tries to do it all over again), but the idea there seems more confused than anything satirical (why, after all this, would anyone allow him near a scientific facility again?), an accidental side-effect rather than something thought up to help explain Brian Donlevy.

It does have its moments--that scene behind glass, of the patient getting up to molest a bunch of flowers, or the girl playing dolly while the monster walks up behind her (a homage, I bet, to a similar scene in James Whale's Frankenstein), or the scene at the zoo the morning after...those moments retain considerable power.

But that ending (warning: revelatory details to follow), lifted from Hawks' 1951 The Thing--I guess they figured if electricity was good enough to cook an out-of-control carrot, it was good enough to fry an oversized cactus. The film in turn went on, I suspect, to influence the 1958 The Blob, where yet another alien went about absorbing other life forms.

Here's what I had to say about the film version of Quatermass and the Pit:

Here's what I had to say about the film version of Quatermass and the Pit:Finally, the real Quatermass steps forward to claim the big screen. Andrew Keir fits Kneale's description of Quatermass the 'troubled scientist,' a far cry from the bullying, bellowing Brian Donlevy (who you felt badly needed a big dose of fiber in his diet).

It's easily Kneale's best work, if only because he finds a science-fictional explanation for magic, mythology and most of Christian theology (with the locust replacing the serpent, and genetic manipulation replacing original sin) and even human evolution (in effect pre-dating Kubrick's 2001 by about a decade (the original TV serial was done in 1958)); this adaptation is remarkably concise, being able to boil down the three hour original to half its length (a few gaps--we never learn why the policeman is so scared, we barely get a glimpse of the little all-night coffee stall before Duncan Lamont's drill operator Sladden (Lamont played the doomed astronaut in the original Quatermass Experiment) rushes by, flinging all the plates around telekinetically.

And one of the most famous moments in the original serial--the first uncovering of the aliens in their chamber, one of them suddenly slipping--is reproduced here, of course, but where in the original it was an accident (one that, happily for the series, had millions of Londoners jumping out of their seats), here it's just a re-staging of said accident, without quite the same impact

(Note: David Edelstein tells a story of how he showed the film to his pregnant wife, and how this moment might have caused her to go into labor--so possibly impact varies depending on the viewer).

But there's still plenty here to enjoy: Roy Ward Baker's sinuous camera moving up and down the London Underground tunnels (the tiled walls and echo-chamber sound giving the place the ambiance of a vast men's room, or a huge abbatoir); Keir as the definitive big-screen Quatermass (he's civilized and compassionate, the same time he's unafraid to speak his mind); Julian Glover as an effectively charming Breen; Barbara Shelley as a lovely and intense Barbara Judd; the aformentioned Lamont as a tremendous Sladden (he does that half-stumble, half-hop of a Martian perfectly, and his howl when explaining what happened is an unsettling mix of terror and exuberance).

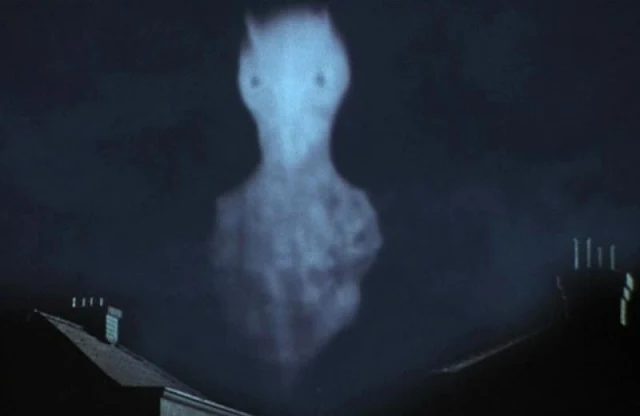

My favorite, though would be James Donald as Rooney, the man who has evolved beyond the Martians' influence. He's a wonderfully off-the-cuff, casual man, and if the antagonism between him and Breen isn't as satisfactorily developed (though Breen's with Quatermass is), Donald does get to stare at Hob (the Martian Satan triumphant) in the face, and his expression is eloquent: a touch of defiance, flavored with not a little disdain, as if saying "you don't scare me, you old devil, let's see how you like this!"

Magnificent, magnificent film. May not have the kind of scares we're used to nowadays, and may not have the scares of the original, where they actually had the time to develop the texture of everyday life in London before they frightened the bejesus out of people (not to mention the strange recording of a Martian purge--'virtual reality' decades before anyone thought to coin the term--is more legible in the serial version), but Kneale's themes and conclusions do come through and they do stay with you. "We are the Martians now," says Barbara in despair--the immediate danger may have been dealt with, but the basic horror remains. No last-minute rescues, no super-secret weapons, no derring-do or even Wells' germs to deliver us; we're all that's left to deal with ourselves the best we can.

Even with a hack job like Halloween III: Season of the Witch you still could taste the unique Kneale flavor: sinister installations, vast conspiracies, a wild and imaginative plot to take over the world.

One of the last things I saw from Kneale was Quatermass, a truncated version of the orignal miniseries. Incoherent and perhaps sour-tempered it may be (it posits a world full of flower children and hippies breaking down), I remember how lovely it was to see Quatermass' granddaughter (granddaughter!) belatedly join the struggle and how sad it was to realize it was his final adventure.

And now Kneale himself is gone. He will be missed.

2 comments:

My bad.

For the record, steve's right; I put a fanzine cover photo on my Kneale post. Now I'm going to have to take it out...

hi mr. vera, glad you're in blogspot now! :)

Post a Comment