One year

I didn't mean to watch Year One (2009)--it seemed to be the least repugnant choice available at the local multiplex--and was surprised to learn that it was directed by Harold Ramis.

One has expectations of Ramis; one can't help having them. He is, after all, the director of Groundhog Day (1993), one of the finest films of the '90s, one of the finest metaphysical films ever made, and about as near-perfect a comedy as anything I can think of in the past sixteen years. Daunting standards to hold a man up to, but Ramis, while never quite reaching so high again, has made a few decent attempts: Stuart Saves His Family (1996), for example, takes an unpromising Saturday Night Live sketch and turns it into a quietly desperate, ultimately moving film about the pleasures and perils of self-affirmation; Multiplicity, made the year after that, posits multiple copies of Michael Keaton scurrying everywhere (a hilarious or horrifying idea, depending on how you take to Keaton). Analyze This (1999) seems like the ultimate idea of the psychiatric patient from hell--it's only halfway realized, but at least the idea had something of the absolute about it.

Judging from the cries of blood surrounding Ramis' latest (Roger Ebert gives the picture one star, spends a whole paragraph discussing the movie's poster, and sums it all up as a "dreary experience"--one gets the impression the man could barely bring himself to engage with the movie, much less like it), Ramis has failed yet again to touch the comic heights of Groundhog (But what else does?). He has failed but surprisingly, despite the unpromising trailer and the generally negative outcry, he does leave an indelible mark.

It's a cross between Mel Brooks' History of the World, Part I (1981) and Monty Python's The Life of Brian ((1979)--Brooks for the formless, across-the centuries format, Python for the subject matter (religious hypocrisy and faith). It's not laugh-out-loud funny, even if it does have more than its share of flinch-worthy gross-out moments; fact is, it's remarkably thoughtful in its treatment of and attitude towards religion and faith. It has a handsome look for a comedy, mostly burnished desert sun and torchlight interiors (checked out cinematographer Alar Kivilo, and the only work of his that stuck out were Sam Raimi's A Simple Plan (1998) and some Sandra Bullock vehicle called The Lake House (2006)), and is competently edited (one expects no less from the director of Groundhog, which is all about editing).

The climax, strangely enough, bears some passing resemblance to that of Ishmael Bernal's Himala (Miracle, 1982)--I'm sure we needn't accuse Ramis of stealing from Bernal, though.

So. Find myself in the strange position of recommending a solidly Hollywood summer movie, and a comedy to boot. Goes to show how accurate 'common consensus' can be, in gauging a picture's quality--sometimes you just have to go and see for yourself.

Icewater

Courtney Hunt's Frozen River (2008) is despite its bleak setting a lovely film. Hunt captures the essence of lower-class living in the colder Northern states--the prefab houses, the junked cars, the temp jobs, the pinched-face people struggling with one scam or another (as either victim or perpetrator) and earning a meager wage, all under the gray skies and endless snowdrifts of upstate New York (some of the scenes look exceptionally difficult to shoot--not only are you dealing with a whitened ground that often radiates more light than the sky, you're dealing with the shifting, often treacherous conditions of the eponymous river itself).

The two protagonists, Ray Eddy (an amazing Melissa Leo) and Lila Littlewolf (Misty Upham) make a good odd couple--they embody their respective social classes (poor white trash, Native-American destitute), they have a genuinely spiky chemistry that makes any possibility of collaboration or friendship seem less than certain, more the result of life's strange vicissitudes than of opportunistic plotting.

The river itself becomes a visual metaphor (a nicely unforced one) for the women's lives--for the kind of fragile, uncertain ice they skate on, struggling to keep their balance, hoping to God the surface of things holds and doesn't drop them into the cold water.

One of Ebert's worst films ever

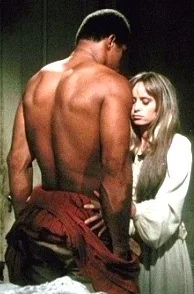

I remember Roger Ebert granting Richard Fleischer's Mandingo (1975) not one but zero stars--apparently the eminent critic, harumphing about "taste," was shocked at all the decadence and exploitation going on, not to mention the sultry, sensual ambiance.

Recommendation enough. It's a startlingly beautiful to look at and despite--or precisely because of--its trashy, melodramatic roots, full of unwholesome energy. It's also declared to be (by film critic Robin Wood, among others) "the greatest film about race ever made in Hollywood." There's always Roots, of course, which aired on broadcast television two years later, but that well-made production doesn't have the inimitable image of James Mason as Southern plantation owner Warren Maxwell, planting his feet on a black boy's belly in the hopes of drawing the rheumatism out of his aging body into the healthy child.

The film is more than the sum of its grotesqueries; Fleischer has taken a Kyle Onstott's pulp potboiler, pruned some (but not all) of the more extreme sadism, given (with the help of writer Norman Wexler) the blacks in the film a social and historical consciousness, overall fashioned a distinctly gothic tragedy. With the help of cinematographer Richard H. Kline (they've collaborated on films like The Boston Strangler (1968) and Soylent Green (1973)) Fleischer has conceived of a doomed, decadent South: the Maxwell mansion is a brooding presence full of huge, shadowy rooms and, despite their wealth, dirt-stained walls (mansions of other families, particularly those with womenfolk, are noticeably better kept); the surrounding forests are lit by dustmote-thickened sunbeams and teem with tropical plants that thrive in the Southern heat.

I can't help but think that the film's violent setpiece, a no-holds-barred bareknuckled fight between two black men with bets placed, may have been the inspiration for the duel to the death in Mario O'Hara's Bagong Hari (The New King, 1986). Other than the common premise, the two sequences couldn't be more different--Fleischer stages his fight as a claustrophobic battle, with teeming crowds on the sidelines and a handheld camera lunging in for closeup shots; O'Hara's is more of an arena event, with tiers rising above and away from the circular floor, torches bordering the battle area, and the camera confining itself to more aloof medium and long shots. Preference for one over another may be a matter of taste--I love O'Hara's cool appreciation of the desperation far below, same time as I like Fleischer's sense of immediacy; I was startled by Fleischer's bloody conclusion, same time I appreciate O'Hara's one wince-inducing moment, involving a meat hook. Both worked with small budgets (O'Hara's being the far smaller), both show a distinct flair for and understanding of violence.

At the film's center is Warren's son Hammond (Perry King), an angel-faced, ostensibly kindhearted plantation owner who at the same time feels more comfortable bedding and deflowering his black 'wenches' than he does bedding Blanche (Susan George), his upper class white wife. Yet he's not above stringing up an old black slave upside-down, and having another slave beat the man's naked bottom bloody with a paddle drilled with holes (to reduce air resistance and speed up the swing). The old slave's crime? Learning to read.

Hammond is in the classic mold of the tragic hero--like, say, Macbeth he is basically a good man, a promising catch for Southern women what with his money and his progressive attitude towards slaves; like Macbeth he never fully realizes the precariousness of his position, never learns that unlimited access to power can lead to its unlimited abuse, and eventual payback. Robert Keser in The Film Journal argues that when matters come to head, when "the crisis peels away Hammond’s velvet glove, revealing his essence as he reverts to violence," he precipitates "the final wave of tragedy." Keser goes on to conclude that "A benign despot with an attractive smile and surface compassion is a despot nonetheless."

I don't quite see it that way. Hammond's moments with his favorite 'wench' Ellen are about as touching as anything I've seen on film, his vow to her that "No one, black or white, gonna take your place" a far more real declaration of matrimony than anything he says to poor Blanche, who is in turn as much a victim as any of the wenches in the Maxwell plantation (she just has more bite, is all). I see Hammond as being an essentially tenderhearted, loving man, who unthinkingly embraces the violence inherent in the institution of slavery; any punishment he instigates is out of obligation, as in the bloodying of that old man's behind (when a cousin walks in and takes over the beating with greater relish, Hammond immediately objects). The real tragedy I think is that a loving heart is not enough; the institution victimizes blacks and their masters alike, robbing both of their humanity as Hammond is gradually robbed of his.

When push finally comes to shove, I don't see the event as Hammond reverting to a violence that was always there so much as it is a matter of a soft heart pierced to the quick, striking out in unaccustomed fury. It's a truism, I suppose, that the gentlest people when provoked express the most extreme reactions, but that's the truism I believe Fleischer had in mind for the film's climax. Hammond has the numbed face of one trying to hide his inner revulsion at what he intends to do, and he carries out his mission with the briskness of one who knows he has to do things quickly, unthinkingly--if he paused to consider, he would fail to go through with it.

In a kind of reverse trajectory, Hammond's favorite buck slave Mede (boxer Ken Norton) gradually gains his humanity. He doesn't have it at film's beginning; in one of his earliest scenes, he's examined and prodded and looked over like a prized racehorse. His preferential treatment is thrown at his face time and again; fellow blacks keep pointing out that on issues that matter, his benign white masters will turn on him. When a runaway slave is about to be hanged, the condemned man looks at Mede and declares "at least I die a free man." As push again comes to shove and Mede finds himself facing the unfortunate end of a rifle barrel, his eventual recovery of the dignity he had lost makes for a stirring counterpoint, a hopeful (if faint) note to contrast against Hammond's own despairing, downward spiral. A great film, absolutely.

12 comments:

Noel, I don´t know if you have read the long piece Andtiditrew Britton wrote on "Mandingo". You can find it in "Britton on film". It´s a fantastic text. In that book there´s at least another great comment, the one he dedicated to Ophüls´ "The reckless moment".

Excellent consideration, Noel. I completely agree: Mandingo is a great film. Thanks for writing about it with such sensitivity and perception. Here's my own take: http://tinyurl.com/5a8zhk

I will look up Britton too!

Thanks Dennis; actually I read your article before doing mine (a sketch, really, not a full-fledged appreciation).

That comparison to the Holocaust is interesting, especially when you ocnsider that whatever the Nazis thought of the Jews, it was nothing compared to what they thought of blacks (and that if they developed their program far enough regarding the Final Solution, the sequel involving the continent of Africa would have taken the horror to an altogether different level).

Check out Philip Dick's Man in the High Castle, if you haven't already--great pulp masterpiece (makes an interesting complementary read to Mandingo, I'll bet), with interesting speculations on Nazi attitudes, if they had developed years beyond the war.

jesus, I'll try look for that, but if it's a book I'll have a time trying to acquire it.

Noel,

Good critique. However, it's Ken Norton the boxer, not Ken Norton the football player.

I read the novel when I was about 16 in 1965. I've never seen the movie. May have seen bits and pieces of it here and there. The impression of the book, as is often the case, I'm afraid would overwhelm a fresh viewing, but after reading your review, I'm tempted to give it shot.

I do remember that those of us who read the novel kind of saw it as over the top deadpan camp. I don't know if I could put the sensibilities of that 16-year old to one side so as to be able to take it straight and neat like you did.

Ted

Ow, really?> Serves me right for being a sports ignoramous. Considere it corrected.

It doesn't feel like pulpy camp, at least where I was sitting, so many years later. The initial reviews did treat it as camp, but I wonderhow they were colored by the book's rep. I know the book's ending differs in the details (more grisly, for one).

Let me know if you see it. For the record, Dave Kehr thinks the world of Fleischer--puts him above, say Ingmar Bergman. Don't know if I'd agree outright, but Fleischer's been badly overrated, I agree that much, especially in the last few decades.

Yeah, it's quite minor, trivial even, the Ken Norton boxer thing. Probably the only reason I caught it is that the novelty of having Norton was kind of publicized back then. I'm no big sports fan generally either.

As for Fleischer being bigger than Bergman, I wouldn't know. I'm not that big a Bergman fan, anyway. I'll only say that being the director of The Narrow Margin and of The Happy Time demonstrates something in the nature of a pretty wide range.

Narrow Margin, definitely.

Ironic to think Kurosawa was to direct the Japanese end of Tora! Tora! Tora! because he thought David Lean would direct the American half, and when he learned Fleischer would direct, he got himself fired. Now Fleischer's stock is on the rise, and Kurosawa's is dipping.

I'd definitely catch Year One...

I do identify myself well with Jack Black - hey, I even endured Nacho Libre.

Still wondering if that (as well as the abovementioned Bruno) may ever reach Philippine shores...I'm still stubborn against openly patronising pirated DVDs

Not a fan of Ramis. His movies are not very god and often immoral.

Huh. I can see not very good--he's often inconsistent, even within the movie (this movie), but how so immoral?

Belated correction: I meant to write "Fleischer is badly underrated" not "overrated." In no way was he ever overrated.

Post a Comment