The Man with the Golden Palm

Earlier this week all the newspaper articles came out about a Filipino winning an award at the Cannes International Film Festival. And not just any award; he had bagged the Golden Palm, the highest honor the festival can bestow.

True, it’s for the Short Films Category…but it’s a genuine Palme d’Or, and as in the Feature Films Category, the filmmaker was up against ten other competitors from all over the world (having beat out a reported seven hundred other entries, also from all over the world, just to enter). The list of jury members is impressive, including as it does Hollywood actress Mira Sorvino (Academy Award winner for her role in Woody Allen’s Mighty Aphrodite), filmmaker Claire Denis (Chocolat, I Can’t Sleep, Beau Travail), and filmmaker Luc Dardenne (La Promesse, the 1999 Palme d’Or-winning Rosetta) as jury head.

Even the list of competing films--in outline, at least--appears varied and not uninteresting. They come from all over--from England, Belgium, France, New Zealand, Brazil, Norway, Australia, Korea, and Russia. The Russian entry, Sergei Ovtcharov’s La Pomme, is an animated short featuring the tales of Efim Chestnyakov, a painter, writer, and poet; the New Zealand entry, James Cunningham’s Infection, is a digital animated film about a superhero hand with three fingers.

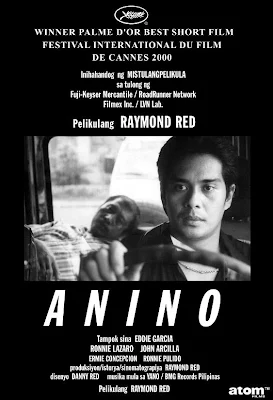

Raymond Red’s Anino (Shadow, 2000) is a thirteen-minute short about a photographer from the provinces (Ronnie Lazaro) wandering about the streets of Manila. He meets a man in black (John Arcilla) just outside a church, and is nearly run over by an old man driving a car (Eddie Garcia); in between, he has a quiet interlude with a child (Ronnie Pulido). People meet, then meet again; harsh words are spoken, and violence inflicted. The film ends on what may be seen as either a hopeful or ironic note--it’s up to you to decide which.

The film is beautifully shot (on 35-mm film stock) and the storytelling, while terse, is often strange. The film has an improvisatory feel; there are moments where you aren’t sure what direction the story is going to take--and, you suspect, the filmmaker doesn’t either. It doesn’t feel as if Red has lost control when this happens, though; on the contrary, it’s as if he’s confident enough to let events flow, taking him--and us--to wherever the currents out there will take us.

It’s the first Golden Palm for the Philippines and it’s quite an achievement, considering that great Filipino filmmakers like Mike De Leon, and Lino Brocka--both veterans of Cannes--have never won a Grand Prix, or even a Special Jury Prize. For a country crushed by reports of a generally depressed economy, political scandals, bank closings, kidnappings, terrorist bombings and accusations of having started the Love Bug virus, this is more than welcome news.

The irony in all this is that everyone seems to treat Red as some kind of hotshot newcomer out of nowhere when in fact he is not, far from it. He’s actually been making short films since 1982, having done two feature films, a TV movie, and countless commercials along the way.

His first short Ang Magpakailanman (Eternity, 1982) is, in its twenty-five densely packed minutes, possibly one of the strangest Filipino films ever made. Its casually freewheeling camerawork evokes the giddy freedom of silent films, when the camera wasn’t tied down by cumbersome sound equipment; its oddly angled shots and shadowy visual textures recall the German Expressionists.

It’s about a young man named Juan who suffers from crucifixion nightmares when asleep, endures the contempt of a fat man in an old office when awake, and is followed around by mysterious woman in a black veil. Later he searches for a book, "Ang Magpakailanman," which has the power to grant immortality--sort of like Roman Polanski’s The Ninth Gate on a smaller budget and wilder imagination. The film, which Red shot, wrote, and directed, went on to win the 1983 Experimental Cinema of the Philippines’ student film competition, and is listed in the Cultural Center of the Philippines Encyclopedia on Film as one of the significant works of Philippine cinema. Not bad for a budding filmmaker only seventeen years of age.

His next few films--Kamada (Companion), Hikab (Asthma), Kabaka (Buddy), and Pelikula (Film)--were seen by British film critic Tony Rayns. Rayns (presently Asian programmer for the Vancouver film festival and consultant for Pusan), who was astonished to find in the Philippines of the mid-‘80s a thriving independent filmmaking community. He was particularly impressed with Red, calling him “a talent on a Wellesian scale; this kid of 21 can do anything--write, direct, edit, operate a camera.” Rayns compared the flavor of Red’s films to Franz Kafka and Jorge Luis Borges--writers Red only began reading when he was told his films resembled their works.

In 1986, a collection of Red’s short films went to festivals in both Edinburgh and Hawaii (where Red met Taiwanese filmmaker Hou Hsiao-Hsien); to the Berlin Festival’s prestigious Forum section and to Hong Kong in 1987; to the PIA Film Festival in Tokyo; to an eight-city tour of Germany, and a ten-city tour of United States. Along the way, his Sketches won a minor prize in the 1987 Montreal Short Film Festival, and he did a music video in 1988 called Filipino Artist in Berlin, where he filmed people spray-painting the Berlin Wall.

In 1992 he made his first feature film, Bayani, (Hero) about the Philippine revolution of 1896. Red, who proved that he was a master of the short film form, had trouble trying to tell a story in ninety minutes instead of nine; despite the film’s arresting visual style, the story felt inert, stillborn. Nevertheless, the film went to Berlin’s Forum section, then competed in the Tokyo Film Festival.

In 1993, Red made Sakay, about the famous Filipino bandit (or revolutionary, depending on how you saw him) who fought against the Americans during the Philippine-American war. Again the drama seemed lifeless, despite some arresting images.

In 1996, Red remade one of his earlier shorts, Kamada into a TV movie, about a young boarder intrigued by the couple (a man with a cough, a beautiful woman) living in the room next to him. Then he lapsed into a four-year silence (except for the occasional TV commercial), until Anino.

Some excerpts from an interview:

N: How do you feel about winning the award?

R: Overwhelmed. To be honest I didn’t expect it. Of course, on the way to Cannes I was hoping--it’s a competition, after all. But for me getting selected for the competition was already a victory. It was a foot in the door. I know in Cannes they like to show a director’s continuing work--once you get in, they’ll be interested in inviting you in the future.

Also, with the invitation--and I guess, with the win--I can now try selling the film. I spent P150,000 ($4,000) of my own money to make Anino, though if you put a price to everything the film probably cost P400,000 ($10,000).

N: How did you figure all that? What did you spend for, and what was given to you?

R: Fuji Films donated negatives, and print stock. LVN Studios gave me a discounted price on developing the negatives and Roadrunner gave me free postproduction use--negative cutting, sound mixing, everything, though I had to pay for labor. The P150,000 was spent on transport, food, rental. Filmex provided the major equipment--the lights, the cameras.

A lot of the people worked for free--only the crew and set men were paid. The assistant director, the production manager, and the cast were all volunteers.

N: The cast? You mean Eddie Garcia, one of our biggest stars? John Arcilla? Ronnie Lazaro? You just asked them to work for you and they did?

R: Don’t forget Hermie Concepcion--she was the old woman in the church.

N: How about the boy?

R: Ronnie Pulido was given money, gifts, clothes. He’s really a street boy from Malate. What you saw in the film was exactly what he wore in real life--dirty shorts, no shirt, barefoot all the time.

N: What do you think this will mean for Filipino filmmakers?

R: I’m hoping as I said in my speech--which wasn’t prepared, I was caught completely off guard--that this would be a new sign of hope for all of us. That this would prove the Filipino filmmaker is as good as any in the world.

N: What do you mean you weren’t prepared?

R: The other shorts were very, very good. The French film, for example, was really outstanding. Then there was this New Zealand film--

N: You mean Infection, the digital animation--

R: That one was technically superior. I told myself, if the judges went by technical standards, the New Zealand film should win. Dolby sound, perfect prints, the color grading was outstanding. At least I could say of my own film that it achieved a certain level of quality that won’t distract the viewers.

N: What gave you the idea for the film?

R: I’ve had the story of the film in my mind for some time. I had the idea of someone--a laborer, I was thinking--wandering the city, and that this would show the gap between rich and poor, powerful and oppressed, etcetera. I also had the idea of a rich man confronting a poor man, what they would do, and a scene where the hero confronts a strange man in a church.

Then in 1999 I went to the Pusan Festival, and saw the new cinema in Korea. I also saw how the Koreans watched Lino Brocka’s Maynila Sa Mga Kuko Ng Liwanag (Manila in the Claws of Neon) and how strongly they reacted, and I said to myself “I wish I could move an audience like that.”

Then I went to the Shang Yang Festival in China, where I met Zhang Yimou again (we had met twice before, in Berlin, 1987, and Rotterdam, 1993). His Not One Less inspired me in my approach, especially the camerawork--a lot of telephoto shots, a lot of semi-documentary stolen shot, a lot of realism. I thought--that’s how to do it. Shoot my film in the streets of Manila, with the actors interacting with real people. Improvise the dialogue. Even the scene with John and Ronnie in church was improvised--I fed them a few basic ideas, then left them to develop it.

N: What was it like trying to make this film?

R: I had a very hard time. I was producing the film and directing it. I was doing a lot of the work myself--making the props, putting on blood makeup on Ronnie, trying to figure out where the cast and crew will eat. I don’t mean no one else worked hard. Bong Salaveria the assistant director was a big, big help--he did the blocking, he talked to the actors, among other things. Most of the people working on film were filmmakers--Ruben did sound, he did a good job using primitive equipment, and him and several others all pitched in for free. It was difficult but fun and fulfilling--the first film for a long time where I had total freedom.

I have to admit this--I didn’t have total freedom in Bayani, Sakay, and Kamada. You would think I was free in Bayani since it was funded by a grant--but even there I struggled with different sides as to what to do. There was pressure from the producer, and from ZDF (2nd German Television). They were thinking of a TV movie to be shown on German TV, I was thinking of a Filipino film. Pressure from local filmmakers--after all, this is my first feature. Can I measure up?

Bayani didn’t turn out the way I wanted. I was also a co-producer, so I couldn’t concentrate on what I wanted to do as a director. My biggest mistake was in doing something too ambitious for budget I had--$80,000 for a period film!

It happened again in Sakay” The producers promised freedom, but they also applied pressure. They were trying to help me, but the original timetable was for one year--a year to do additional research, to write the script. We started in early 1993 with a target date of December 1993, or the Metro Manila Film Festival. Midway, it was suddenly announced that we were committed to a June opening, to catch the Manila Film Festival instead! It was a traumatic experience. I haven’t been able to do a feature film since.

N: What about the TV movie?

R: Kamada was an attempt to do something creative. At the same time it was TV. The whole idea was half-baked--you can’t do everything you wanted, not for TV. A TV movie has to be cut up into segments, has to adjust, there is a formula to making a TV movie. I totally disregarded that at first, and it meant trouble later.

But when it finally came out, I thought it wasn’t too bad. It was refreshing to see something different like that broadcasted on TV.

But Kamada wasn’t supposed to be the only remake of one of my short films; Sketches for the Sky was a first draft for a full-length film, Ang Himpapawid (The Wind). That was the original project I submitted and got a grant for.

It was going to be about these two men in the Philippine-American War, and they are trying to build the first flying machine. They don’t care about the war; all they care about is flying. Then they read about the Wright brothers, lose heart, give up, and end up helping in the war anyway.

N: That would have been a great film to do.

R: Unfortunately, I was in Berlin writing the screenplay and missing the Philippines, so I started to read some history books, and became interested in the Philippine Revolution. So I asked if I could do that instead, and I ended up doing Bayani. It might have been the biggest mistake of my life…

N: Is Anino your favorite among your works?

R: Anino is one of the films I enjoyed doing, and where I had total control. The people really believed in what I was doing, and totally supported me.

N: And your next project is…?

R: Makapili was written with my writing collaborator Ian Victoriano--he did Sakay and Kamada--on a Huber Bals grant which the Rotterdam Festival awarded to us in 1993. That was seven years ago.

I presented GMA Studios with a storyline; I didn’t want to give them a script until I got co-producer credits and full creative control. Unusual, but it’s been done in Europe. Derek Jarman does it all the time, just pitch a proposal to Channel 4. They can see that I don’t do it for the money. Trust me and my treatment, and I’ll show the screenplay.

It’s more or less finished, but still evolving. Producers want to see screenplay, then commit. I want commitment, before I show them the screenplay. A chicken and egg thing. I may be dreaming, but the changes I will do are not costly. I want to change lines, do improvisation. One of the reasons I did Anino was to prove that it could be done. Using Eddie Garcia proved it could be done with a major actor. He improvised most of his dialogue.

N: I noticed something common in all your films. In Ang Magpakailanman, there was a playfulness, a willingness to toy with the medium. The way you shot everything in fast motion, for example…

R: Ang Magpakailanman was my way of emulating a silent movie. I didn’t have black and white super 8 film, so the next best thing was to tint the print and show it in speeded-up motion to get that old-fashioned, silent movie effect.

Essentially, I was looking from the point of view of a filmmaker from the 1920s trying to make a futuristic comedy. Hence the look of Ang Magpakailanman.

N: It’s that inventiveness of Ang Magpakailanman and of your early shorts that I miss in your feature films.

R: Bayani was half-baked. Not that I don’t like the film, but it was the result of my compromising everything until everyone was happy. I should have stuck to what I wanted. You know what Bayani was really supposed to look like? Something like Woody Allen’s Zelig, a sort of fake documentary. You saw some of that in Bayani’s beginning--stills, voiceovers, some black and white film used sparingly--but I should have gone all the way. If I had gone all the way, I would have been ahead of Forrest Gump.

Sakay was even worse--I was trying to do a straight historical epic, a Gandhi.

N: I see Anino as a return to your more imaginative films, but with a place in it for social realism a la Lino Brocka or Zhang Yimou.

R: Makapili will have something like that. Generally, it’s a straightforward narrative. There is a story, characters developing, intertwining. But there will be elements of the absurd, surrealism, playfulness, a bit of dark humor, deadpan humor. Everything will be real but at the same time frightening. There will be situations that will make people laugh, but laugh out of fear.

We actually want historical accuracy---which is why we are doing so much research. We want the sense of ordinary people caught up in war, set during the Japanese occupation, but we won’t show too much of the Japanese, just the conflict among the Filipinos themselves. This film won’t be about Japanese atrocities; it will be about how war destroys ordinary people, how it drives them into betraying others.

The film will play with the myth of the Makapili that is popular today. Ask any old man today about them, and the reply you will get is that they were informers who wore bayongs--woven bags--over their heads to prevent identification. Man with a bayong on his head, going around, betraying people to the Japanese.

Actually, the Makapili was a movement formed by officers of General Aguinaldo’s former army--colonels, generals and all kinds of officers, so angry with the occupying Americans that they sided with the Japanese. They actually believed the Japanese’ Co-Prosperity Sphere. They felt they were right.

The Makapili were not mere traitors or informers. They were a formal movement. They didn’t wear bayongs over their heads--they were known, the people knew them, they went up to people and pointed to them directly, without hiding. They were proud of what they did, and you can see it in the root words that formed their name, the “Makapilis”--the “Makabayang Pilipinos” (Filipino Nationalists). The film won’t try justify what they did, but it will try and show why they felt justified in what they did.

N: I hope you will be casting unknowns. It doesn’t matter to the international market if the actors are known Filipino stars or not, and you can save on the salaries.

R: That’s another reason why I made Anino--to prove that stars didn’t matter. Ronnie Lazaro isn’t a star, yet he was the one pointed out the most in the film--I talked to some Koreans who found him very charismatic, with expressive eyes. Luc Dardenne, the jury head, came up to Ronnie and told him that he looked very beautiful on the big screen.

N: Any other interesting reactions to Anino?

R: Oh yes. Robert Mallengrau from Belgium came to me immediately after the screening and said he loved the film, it was the best of the lot, but that he may be biased about the Philippines. Some of the festival staff cried when they saw the preview tape--said they felt for Ronnie and the street children. They also said that when they saw it on the big screen, they cried again.

N: And the lesson learned from this entire exercise was…?

R: You have to do what you want; that’s all. Nothing less will do. I forgot that when I did Bayani and Sakay, and I learned that again when I did Anino. You have to do what you want to do. I wanted Eddie Garcia, and I refused to settle for anyone less. I didn’t know him, never met him before. I called him up, said I wanted to work with him, but couldn’t pay him. He said yes.

Likewise with Cannes. I knew it was unlikely, but I called up the website, submitted my application there, faxed in the other requirements, and kept calling long distance to follow up. I spent for the English subtitled video, sent it by DHL, kept faxing. I spent for the subtitling, and for sending the print.

N: That’s unusual; most festivals will pay for the shipping of prints when they’ve been invited.

R: Most festivals, yes, but not Cannes. You have to ship it to them, and they are very strict with deadlines--you have to follow them exactly. But they will pay to ship it back to you. At least they will do that much for you.

9 comments:

Thanks for the post, Noel, it was very interesting, and definitely made me want to see the film in question. I've added your link to the Short Film blog-a-thon

Sure thing, Ed! The tragedy of shorts is that they're not very well distributed. I'd like to see Red's shorts collected in a DVD someday...

The film itself is available on the Atom films website. Thanks for the interesting article. I was Googling the director's name when I stumbled upon the film itself.

http://www.atomfilms.com/film/shadows.jsp

good day! does any know where i can find the short fil KAMADA by sir raymond red? thanks

Interesting artik. There's a Filipino short called "Sabongero" that's nominated in Cannes this year.

http://sabongeromovie.multiply.com/

I don't usually allow ads, but this being a Filipino short, I'm cool. And here's the link, properly posted. Good luck

Sabongero

Where can I download that short film? I'm a mass communication student. PLEASE? Any link?

I don't know. Caught it in the UP Film Center and several other screenings.

Post a Comment