Dutt's Entertainment: ten immortal Indian musicals

When most people think of Indian movies, they think of Bollywood, of men and women in colorful costumes, dancing and singing before elaborate sets; when more knowing people think of Indian movies they also think of Satyajit Ray and his brand of understated realism. The world's perception of Indian cinema remains fixed on a juxtaposition of these two extremes-- extravagant commercialism vs. austere arthouse. Film critic Pauline Kael didn't help matters when she said "Ray is the only Indian director; he is, as yet, in a class by himself...the Indian film industry is so thoroughly corrupt that Ray could start fresh, as if it did not exist..."

Which is an amazing statement, one she'd probably never have made if she knew better-- if, say, she had sampled the gritty neorealism of Bimal Roy's Bandini or Raj Kapoor's Awaara, the elemental power of Mehboob Khan's Mother India, the noirish gloom of Guru Dutt's Pyaasa. Indian cinema is a grand buffet of different styles and subcultures, from Bengali (not just Ray, but Ritwik Ghatak, and Mrinal Sen) to Bollywood; Ray didn't just come out of a vacuum but out of a teeming sea of productive filmmaking, most of which are wonderful musicals, some of which have a strong thread of realism and social commentary running through them that surely influenced him, and which he in turn influenced. Roy, Kapoor, Mehboob and Dutt among others made money and won large audiences; they worked in a strictly commercial format, but made films that were at the same time recognizably art.

By way of introduction to this turbulently colorful film culture, particularly to the usually disparaged form of the Indian musical, here is a list of my favorites, in ascending order:

Half Ticket

Credits say Kalidas directed and Ramesh Pant wrote Half Ticket (1962) but every aspect of the movie bears the fingerprints of its star, Kishore Kumar-- the first Indian comic actor to break out of the sidekick roles usually handed to comedians and assume the lead in his own pictures (Kumar also has a wonderful voice, and worked a second career as a successful playback singer). The film is haphazardly made, with indifferent black-and-white camerawork and editing that tends to jump, sometimes over entire scenes, making hash of what story there is. Possibly it's the source print from which the DVD was made-- I wouldn't be surprised to learn that the original negative was poorly maintained and has since deteriorated; I would be equally unsurprised to learn that this was the movie's final form when it was commercially screened. Comedy has never enjoyed much respect, even in India (especially in India?); you'd be hard-put to find a picture where the makers actually cared enough to polish their work, much less preserve it.

But Half Ticket doesn't really need polish; all it needs is Kumar, who delivers a monumentally funny performance as Vijay, the good-for-nothing, irrepressibly mischievous son of a rich industrialist. The film's story is suitably bizarre: Vijay dabbles in socialism and doesn't think twice of delivering pro-labor speeches in front of his own father's workers. He is summarily thrown out of his own house, decides to take a train to Bombay to find a job, but can't afford the ticket; undaunted, he transforms himself into Munna, an outsized brat with lollipop in hand, and buys a "half-ticket," a half-price ticket for children. Along the way he meets Asha (Madhubala), a beautiful woman taken in by his childlike helplessness, and Raja Babu (Pran), a jewel smuggler who surreptitiously slips a diamond in his pocket. The rest of the film has Raja running after Munna and the rock in his pocket while Munna runs after Asha, the love of his life.

Kumar's Vijay/Munna ranks up there with the creations of Harry Langdon, Harpo Marx and, more recently, early Jim Carrey as great obsessives who pursue with insane intensity-- no one is quite sure just what. Good food, certainly; sometimes the curve of a woman's admirable behind (sometimes, as in Langdon's case, not); the satisfaction of justice being done, and damn the cost. In one especially deranged scene Vijay is in line waiting to be interviewed; he learns that to get the job he needs to "spread a little butter," so to speak, and when he meets the interviewer proceeds to do exactly that: with two fingers of one hand, all over the helpless victim's face. Pointed satire on corrupt labor practices, of course, and totally in keeping with Vijay's character (remember he used to deliver pro-labor speeches), but the method of execution is pure Kumar. This, I think, is for the ages.

Mughal-E-Azam

This film made in 1960 and set sometime during the reign of the Mughal emperors is easily the most resplendent Indian musical I've ever seen-- which is saying something, as Bollywood musicals are not known for their restrained art direction or lukewarm color schemes. K. Asif's epic tale (from a screenplay by Asif and Aman) takes the legendary (and largely apocryphal) love between Prince Salim (Dilip Kumar), son of Emperor Akbar (Prithviraj Kapoor, father of filmmaker Raj Kapoor), and Anarkali (Madhubala), a lowly but beautiful commoner, turns their tragic affair into a visual feast for the eyes. Like the Taj Mahal (another Mughal extravagance) the film is assembled from elements found all over India: costumes from Delhi tailors, embroidery from Surat-Khambayat, elaborate footwear from Agra, armor and weaponry from Rajasthani blacksmiths, jewelry from Hyderabad goldsmiths, and, for just one musical number, a chorus of one hundred singers.

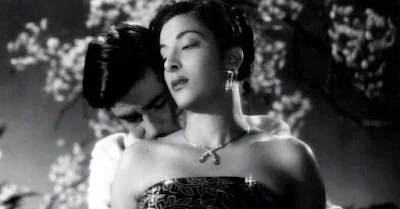

The result is a fevered dream of a movie, with opulence enough to rival even that of the original Mughals: terrace upon terrace of women dance, weaving intricate choreography; a little boat with a message (actually, a lotus leaf with paper inserted into the flower petals) floats down canal after canal (the imperial palace's beautiful yet functional central air-conditioning system) to its intended recipient; in one rare sequence-- most of the picture (shot by R.D. Mathur) is in black and white, which you can't help but think is a blessed respite from all the indulgence-- the screen bursts into full color, and a woman dances in the famously ornate Sheesh Mahal, the Palace of Mirrors. The thousands upon thousands of mirrors and crystals and flashing jewelry are enough to put your eyes out-- or make you almost wish they had.

All this would be pointless if there wasn't a drama strong enough to dominate the overpowering décor; luckily we have Kumar's flashing dark eyes locked with Kapoor's imperious glare in mortal combat, a battle of wills sorely testing their relationship as father and son. Caught in between is Madhubala as an innocent dancer who adores her Prince and will do anything for him, even at the cost of her life, even at the cost of her love.

It may be Madhubala's finest performance, and she never looked more beautiful; as a sculptor who used her as model puts it, when they see her "soldiers shall lay down their swords, emperors their crowns, and men will carve out their hearts in oblation." The sculpture is veiled; to uncover it, Prince Salim shoots an arrow at the veil's knot-- revealing the live girl hidden underneath. "But that arrow was aimed at you," Salim exclaims; "why did you stand still?" Kalyani's cool reply: "I wanted to see how stories are made to come true." What she felt with that arrow pointed at her through the veil, waiting for anything to happen-- that's the kind of thrill Mughal-E-Azam is likely to inspire in us the viewers.

Satyam, Shivam, Sundaram

Then there is Raj Kapoor, one of the finest and most commercially successful of Bollywood filmmakers, with a directing career spanning thirty-seven years (his acting career was, if anything, even longer). Satyam, Shivam, Sundaram (Love Sublime, 1978), which Kapoor directed from a script by Jainendra Jain, turns on an intriguing figure: beautiful Rupa (the voluptuous Zeenat Aman) who cannot find herself a man, first because she's thought to be unlucky, second because she's disfigured by a hideous burn scar. True to her unlucky nature she falls in love with Rajeev (Shashi Kapoor, Raj's brother), an engineer working on a nearby dam who not only believes she's perfect (somehow she manages to conceal her scar) but is pathologically incapable of tolerating ugliness of any kind.

The movie, made late in Kapoor's career, is famous (or infamous) its sensuality; various scenes have Aman exposing increasing amounts of skin and cleavage, includes a number by a waterfall where she wears a see-through sari, and climaxes (literally) with an actual, honest-to-goodness kiss with Shashi Kapoor (I replayed it on my DVD player to confirm I really saw it). But there's much more than just the titillation; Kapoor's direction brings out interesting psychological nuances. Rupa as fleshed out (literally) by Aman is a sensual creature, given to wearing two-piece bikinis in musical numbers that barely contain her generous nature, fore and aft (the rationale is given in an ingenious throwaway line: that her father refused to spend for clothes, hence everything is several sizes too small). Her unlucky status and scar have been hammered into her consciousness for so long it's the only thing she can see; it gives her a reserve, a becoming humility able to enchant any pair of testicular sacs that walk by (helps that Rupa has a lovely singing voice Shashi hears before actually seeing her). I might add that Aman's habit of masking her scar by biting the edge of a veil with her teeth is unbearably sexy-- you badly want to be that bit of veil caught in her teeth.

Rajeev is a piece of work; when he hears Rupa's voice he tells himself that a woman who sings so beautifully must herself be beautiful. When he finally sees the scar-- this right after their wedding-- he goes wild, believing he's married the wrong woman, running off to look for the right one. Rupa humors him and puts back her veil, and astonishingly Rajeev buys this bit of business; he shuns the half-monstrous wife at home, throws himself at the half-cloaked mistress he meets at the waterfalls (their favorite trysting place). Makes you wonder about human nature, and its powers of self-delusion.

Raj Kapoor lines his tale with a luxurious visual texture and color scheme that would put Moulin Rouge to shame (cinematography by Radhu Karmakar), all tinkling waterfalls (recreated because Kapoor couldn't find a cascade elaborate enough to satisfy him) and ravishing sunsets (so frequent you wonder why the film doesn't all take place at night); when he photographs Rajeev's dam there's a hair-raising sense of power barely held in check-- Kapoor is saying something here about women and the fury unleashed when they feel grievously wronged. Or, as Rupa so eloquently puts it: "The heart breaks soundlessly but when it does the earth quakes, the heavens open, the world ends." A rip-roaring melodrama that approaches the size and scale of genuine tragedy, and a great Bollywood musical.

Sangam

Kapoor's Sangam (Union, 1964) tells of a love triangle between Sunder (Raj Kapoor), Radha (Vyjayantimala, a real beauty) and Gopal (Rajendra Kumar). Sunder the buffoon loves Radha, who loves the tall and handsome Gopal; Radha rejects Sunder flat out, telling him a man can't always be a clown, but always seems to have trouble letting Gopal know about her love for him. Later, when Sunder reads Radha's love letter meant for Gopal and thinks it's for him, he finds the courage to join the Air Force (before this he used to fly planes for the fun of it). Sunder makes Gopal promise not to let any man come between him and Radha, then flies off on a dangerous mission from which he ends up reported missing presumed dead.

Pearl Harbor, anyone? Not fair-- Sangam is a far better film. Kapoor knows how to make his characters engaging, full of charm and light comic banter (no small thanks to a solid script by Inder Raj Anand), and he really, really knows how to use the wide screen-- the film's visual opulence and rich color palette (again, by Radhu Karmakar) reminds me of Luchino Visconti, only with less pretension and better humor.

And then there's the subtext. It grew more and more apparent watching the film that Radha has trouble trying to land Gopal because Gopal isn't really interested in her, but in Sunder. So-- when Sunder is reported dead and Gopal starts courting Radha, his motivation is obvious: 1) he's displacing his love for Sunder to the girl, and 2) this girl is the one person in the whole world who matters to Sunder, and, as promised, Gopal must take care of her as best he can; what better way than as his lawfully wedded wife?

When Sunder turns up alive it's all too easy for Gopal to explain his promise to Radha and break off their courtship, telling her "friendship is more important to me than my happiness." Radha, heartbroken, marries Sunder; Gopal is content to stay in the sidelines, single.

Does this make sense at all? Let me put it this way-- do you believe a guy would throw over the love of his life for his best friend? Only if his best friend is the love of his life.

Okay, so-- Radha and Sunder have been married a year, during which Radha really looks like she's learning to love Sunder--

Then Sunder discovers an unsigned love letter Gopal once wrote to Radha, goes berserk, pulls out a gun. Radha manages to take the gun away from him, but runs out of their house in a state of panic…

And where does she go? To the one man who can help her, of course. And where does Sunder go?

My theory about Gopal's behavior is this: he's loved Sunder for years-- has in fact stayed away hoping to 1) keep Sunder happy with Radha, and 2) masochistically enjoy his loneliness. When the whole situation blows up and he sees Sunder's devastated face, Gopal realizes that he's been going about this the wrong way, that the most effective way to gain the attention of his true love isn't to help him but to hurt him, preferably with the truth. After which he can consolidate his victory by placing his love forever out of Sunder's reach, beyond anything else Radha can possibly do…

Did Kapoor know what he was doing? Did he realize how interesting his film really was, functioning on one level as a wonderfully shameless melodrama and on another as a repressed love affair, and coming up with sound psychology for both storylines?

Oh, and there's a scene in a party where the guests all rise up and ask Radha to sing for them-- this after Radha had just had a stormy confrontation with Sunder over the letter. Radha whispers: "How can I sing now, of all times?" Sunder replies: "But of course; now is the perfect time for you to sing." And he's right, I thought: in the world of the Indian musical this of all times was the perfect moment for a musical number.

Pakeezah

Kamal Amrohi struggled for ten years to make Pakeezah (The Pure One, 1972), all the while having to deal with lack of money and the chronic ill health and alcoholism of his wife, Meena Kumari (the star of the picture, who died shortly after finishing the film).

The results are difficult to describe. The sets, for example-- think A Thousand and One Nights, or splendor on the level of the Mughal emperors (remember 'Mughal' is the basis of the word 'movie mogul"-- only the Mughals make modern Hollywood moguls look miserly in comparison): graceful Islamic arches, endless rectangular pools (the Mughal equivalent of central air-conditioning); vast, thick-woven carpets. When Kumari lies down to sleep, her hair is lowered into a huge bowl of water fed by a tinkling fountain-- presumably to keep the strands lustrous and moist.

Kumari is beautiful, but in an almost Oriental way-- slanted eyes, oval face, delicate nose and lips. The musical numbers are designed to showcase her dancing-- simple, stately dolly shots capture her simple steps (actually Kumari wasn't much of a dancer) as she pranced her way through complex, fully built sets. Amrohi makes sure you see architectural detail even in the far distance, as the camera swings around; the color camerawork (by Josef Wirsching and-- again-- R.D. Mathur) is the loveliest money can buy, all the more impressive since money wasn't always available.

But more than the set design and photography, there's a real sensibility working here. Amrohi seems to want to say something about the passage of beauty, how this very transience is in itself beautiful. He repeatedly shoots lights and lamps waning; has about a dozen shots of utterly gorgeous sunsets. There's a progression too, from the perfumed atmosphere of the palace where the film's first half is set to the even more beautiful outdoors (the coalglow dusks; the mountaintop view of a chain of waterfalls) where Kumari meets her true love.

None of this would work, or all would just be an exercise in excessive Bollywood style if there wasn't a gripping tale to tell. The story (the screenplay of which Amrohi also wrote) is as old as Camille or La Traviata-- young man from wealthy family falls in love with a prostitute named Sahibjaan-- but Amrohi includes the story of the girl's mother (also Kumari), yet another prostitute who fell for a wealthy young man and ends badly. The circularity adds suspense: you wonder if the daughter will end up the same way.

One more thing-- Amrohi, for all the seeming slavishness of his devotion to his wife, presents her as selfless martyr saved by the goodness of a noble husband. You might say that at the core of every tribute no matter how extravagant no matter how selfless is a kernel of egotism. Considered one of the greatest Bollywood films ever made; can't say I completely disagree.

Bandini

Based on a book by Jarasandha, a former jail superintendent (with a screenplay by M. Gosh and Nabendu Gosh, and dialogue by Paul Mahendra), this is considered filmmaking legend Bimal Roy's finest film-- even over his Do Bigha Zamin, which won at Cannes. It's the story of Kalyani (Nutan), a convict who while working in the prison hospital captures the heart of Dr. Deven (Dharmendra). The doctor proposes to her, is refused, applies for transfer out of the prison.

When the sympathetic warden investigates, Kalyani is unable to explain her refusal; she instead confesses everything through a diary, and the film goes into a long flashback-- about how she once loved an imprisoned revolutionary named Bikash Gosh (Ashok Kumar), how they ultimately lost each other.

Roy meant the film to be a plea for rehabilitation of convicts; unfortunately his heroine is so saintly and pure, the people around her so sympathetic and ready to listen, that all that seems to stand in the way of a full pardon is the paperwork (when it comes to women in prison films I prefer the sullenly pregnant convict Filipina actress Nora Aunor played in Mario O'Hara's Bulaklak sa City Jail (Flowers of the City Jail)-- her path to redemption seems more interestingly rocky). But if we're talking sheer, unadulterated suffering, Kalyani is up there with world-class masochists; as played by the beautiful Nutan, she makes us feel every pang of her pain and loss, every shuffling step of the way.

Visually it's stunning, thanks to Roy and Kamal Bose's black-and-white cinematography; there are few images more moving in all of Indian cinema than that of Kalyani sitting small and alone before the great prison walls, a shaft of sunlight picking her out from the deep shadows. A woman sings a plaintive song while turning a stone mill, and Roy only has to lift his camera a bit to present the wheel to us, grain pouring down one hole-- as apt a metaphor as any for the way women's lives seem to pour down a hole to be crushed by spinning stones.

Mother India

Raj Kapoor has acted opposite many beautiful women in his films, but none had the same fire, or ignited the same kind of chemistry in him as Nargis; for some four to five years she worked exclusively for Kapoor, even refusing to act in her mentor Mehboob Khan's projects. Then the pair broke up, and Mehboob immediately offered Nargis the role of her career, as the indestructible matriarch of Mother India.

It's been called the Indian Gone With the Wind, though the comparison seems not just irrelevant but insulting; I much prefer this. The drama (thanks to a screenplay by Khan, Wajahat Mirza, and S. Ali Raza) feels bigger, the suffering more profound; the challenges our heroine Radha faces, most of the time alone and without the support of friends or neighbors, would bring any number of Scarlett O'Haras to their knees. Nargis plays Radha like a force of nature; where elaborate sets and extravagant production design help lend Gone With the Wind a larger-than-life quality, it's mostly Nargis who gives Mother India its monumental scale (with some help from Faredoon A. Irani's gorgeous cinematography). To see her broken down by adversity and a severe flood, then somehow rise to her feet and shake a defiant fist at the skies is to see a woman embody the very spirit of a nation; you feel appalled at the size of her task, awed at the extent to which she actually succeeds.

Of course, it helps to have a few subsidiary characters, to give Radha's figure contrast and scale-- in this case, Sukhilala (Kanhaiyalal), the repulsively unctuous moneylender who not only ties Radha's family down with an ever-growing mountain of debt but actually lusts after Radha, hoping to make her his own. In the film's latter half Radha's own son Biju (Sunil Dutt) becomes the source of her troubles, eventually forcing her to test which value she holds up higher: her mother's love for her son, or her woman's love for her-- or any woman's-- honor.

Awaara

Raj Kapoor's breakthrough picture (the title translates to 'vagabond') builds on a strong premise (and a strong screenplay, by K.A. Abbas): a judge (played by Raj's father, Prithviraj Kapoor) throws out his wife when he believes (wrongly) that she had been raped and impregnated by a bandit out for revenge (the judge had once sent the bandit to prison); years later, the boy Raju (played by Raj Kapoor) has grown to become a petty criminal and vagabond. It's the issue of nature vs. nurture, as Kapoor shows us how social class and circumstance can straitjacket a man-- which may explain why the film was a big hit not just in India but in the Soviet Union.

Awaara is an amazing work, with a black and white visual style (thanks yet again to Kapoor regular Radhu Karmakar) and other elements borrowed from a number of filmmakers. You can see how much Kapoor has learned from past masters-- the shadowy look of the hideout where the judge's wife is held prisoner recalls Welles' Macbeth; scenes of Raju's childhood in the slums have the realism of de Sica's Bicycle Thieves or Ford's Grapes of Wrath; along the way, a dream sequence straight out of Busby Berkely. Kapoor's vagabond Raju, of course, is a variation on Chaplin's famous tramp.

But it's more than just borrowing from great directors-- Sholay shows traces of Peckinpah and Leone, but clumsily done-- Kapoor takes his influences and fashions something fresh; you might say that where most Indian musicals use a variety of colors and locales to keep the audience entertained, Kapoor uses a variety of film styles (he would show more restraint in films like Sangam and Satyam, Shivam, Sundaram).

Kapoor doesn't always depend on razzle-dazzle-- in one scene Raju steals the purse of a beautiful girl named Rita (Nargis), then, conscience-stricken, contrives to chase after an imaginary thief, jumping over a brick wall to beat the robber while Rita (with increasing alarm) listens from the other side, ultimately returning the purse without her any wiser. A simple joke, and a deft metaphor for the movie's theme-- Raju must fight his own conflicted nature to win Rita's trust. Raju also has a favorite line, whenever he's suspected of being a pickpocket, piano tuner, or car thief: "it's not your fault it's my face." The line grows funnier and more meaningful every time it's repeated.

Actually, despite a few heavy-handed speeches-- which didn't feel all that heavy, actually, since Kapoor drops them where they'd be most expected (some dramatic high points, the trial scene), and they're not delivered in an overwrought manner (as in Mani Rathnam's Bombay)-- I thought the film effectively worked out its themes. The real villain here isn't the bandit who kidnaps Kapoor's mother but Kapoor's father, who insists that a bad man stays bad-- the bandit had been innocent when first captured, but since father and grandfather were criminals the judge took it for granted he was one too; it’s this presumption that drives the bandit to such cruelty. The film shows us that the corollary is equally untrue-- that the issue of a decent man, in this case the judge's son, can't stay good if circumstances won't allow him. Any man can fall into evil, and the cause can be something as simple and frighteningly arbitrary as the plot twists of a Bollywood musical.

A note on Nargis: newly introduced, you might say "she's not pretty-- she's got a nose like an aardvark and a curled upper lip." Nargis' beauty is the kind that grows on you as the movie progresses-- by film's end you realize that her expressive face and effortless acting have wiped out practically every other actress from memory, Indian or otherwise (with possible exception of Waheeda Rehman-- but Nargis is the far better actress). She fully incarnates Kapoor's motive for reforming himself-- you can understand why he would do anything to win the admiration of those eyes, the approval of that smile (it's in the league of Ingrid Bergman's). Kapoor couldn't resist letting some of that chemistry spill over into his real life; his relationship with Nargis reportedly wreaked havoc on his marriage. Great Bollywood musical, one of the greatest, I think.

Kaagaz ke Phool

Guru Dutt started out in the Prabhat Film Company where he befriended struggling actor Dev Anand, who promised that if he ever became famous, Dutt would direct one of his films; Anand became famous, so Dutt directed Baazi (The Game) in 1951.

Dutt would go on to make a series of excellent and commercially successful musicals, from the practically perfect comedy Mr. and Ms. 55 to the darkly noirish Pyaasa; his films are characterized by a distinct visual style, gritty realism, smart dialogue, and sympathy for the underdog (with equally strong disdain for the upperclass cad).

Having raised the bar with his critical and commercial successes, Dutt proceeded to try raise it higher--he took the considerable profits he made from his last hit (Pyaasa) and plowed it into Kaagaz ke Phool (Paper Flowers, 1959), about the decline and fall of a famous filmmaker named Suresh (Dutt) and the simultaneous rise of his beautiful protégé Shanti (Waheeda Rehman). The film is, if anything, even more ambitious, with a beginning that dares evoke the opening of Citizen Kane-- Dutt as the once-famous Suresh, wandering into what looks like an abandoned Xanadu (an empty studio lot).

Dutt employs a battery of special effects-- huge sets, miniature cityscapes, windblown confetti, dramatic shafts of light (devised by master cinematographer V.K. Murthy)-- to create his vision of the Indian filmmaking industry; at one point, he uses swirling crowds and swooping crane shots to suggest the exhilaration one feels when everyone adores you and you sit on the apex of the moviemaking ziggurat. Kaagaz was the biggest film Dutt had ever directed, and, as it turns out, a staggering commercial failure-- Dutt's Intolerance," so to speak, following the success of his Birth of a Nation. Dutt's character as written (by Dutt regular Abrar Alvi) may have been too alienating, his problems too dark and complex for the audience to relate to; scenes involving Suresh's in-laws, including a comic brother-in-law entertainingly if rather pointlessly played by Johnny Walker, suggest entire subplots developed but never successfully integrated.

Kaagaz as a story may have been a commercial failure, but as a collection of visually breathtaking, near-autobiographical moments in a filmmaker's life it's incomparable. At the very heart of the film lies the love between Suresh and Shanti, surely one of the most honestly depicted in all of Indian cinema; watching them, it's easy to believe Dutt was inspired by his real-life infatuation with Rehman. At the same time, Suresh's self-destructiveness is unsparingly portrayed-- a scene where Suresh presents his latest film and the audience riots, tearing up the seats in protest, might have been a preview of Kaagaz's own opening night. Dutt went on to act and produce several more films, but never directed again; you can't help but wonder if his suicide at the age of thirty-nine was but his last desperate attempt to prove a lifelong point: that real life can be as messy, flawed, and unforgettable as what he showed us in this film.

Dutt's masterpiece, Pyaasa (Thirst, 1957) is about an unknown poet named Vijay (Dutt) whose brothers have sold off his poems because he refuses to get a decent job and support his family. He wanders about, homeless and hopeless, and meets Meena (Mala Sinha) an old high school sweetheart who has since married a rich publisher, Mr. Gosh (Rehman); Mr. Gosh hires him, then as quickly fires him when he's caught alone with Meena. Everyone looks down on him, everyone thinks he's a loser except for this one girl, Gulab (the lovely Waheeda Rehman), and she's a prostitute. The plot (from a screenplay by Abrar Alvi) resembles Michael Curtiz's Casablanca (think of Curtiz set to playback music) with the sexes reversed: a crowd-pleasing melodrama about a male Ingrid Bergman (Vijay) who has to choose between Paul Henreid's idealism (Gulab) and Humphrey Bogart's pragmatism (Meena).

Pyaasa is pure bathos, an ultramasochist's fantasy, with the whole film predicated on taking the sufferings of this sensitive young artist seriously. What probably gives the game away (aside from his angelic homelessness, his involvement with two beautiful women, his refined sense of integrity) is the moment where Vijay appears at an auditorium entrance, transfixed by streaming light, his arms stretched out on either side in classic cruciform pose. If it's true that it takes an egotist to think he can be a lead romantic actor and an even bigger egotist to think he can be a filmmaker; how big an egotist would you need to be to think yourself a romantic lead and a serious filmmaker?

What saves Casablanca from being a camp comedy classic is Max Steiner's haunting score, Michael Curtiz's swooping camera, Bogart's sourly solemn puss and (above all) Bergman's performance as the film's forbidden love. Hearing a line like "kees me-- kees me as if for the last time!" it's impossible not to laugh, till you catch sight of Bergman's unbelievably beautiful face and the laughter dies in your throat. Pyaasa has that same kind of transformative magic-- this is hilarious material except for Dutt's mastery of film technique. When Vijay, for example, sings to Meena ("Who knows the kind of people they are?") the camera repeatedly leaps away from him to her, suggesting both the impact his singing is having on her and the enormous social gulf separating them both (think of Spielberg set to playback). Later, Vijay stands brooding on a balcony while Gulab watches from behind; the sequence where she sings, sidling up to and shrinking away from the object of her adoration without him being any wiser, is as skillfully shot and edited a suspense setpiece (Will she hug him? Leave him? Stab him in the back?) as in any noir (think Hitchcock set to playback). Vijay's resurrection in that fateful auditorium as he sings of disillusionment with material wealth ("This world of palaces, of crowns, of thrones") is a thrilling piece of moviemaking, with the crowd rising up in astonishment, then furious riot (think Abel Gance set to playback).

Dutt has a genuine Midas' touch; anything he touches turns into gold. He takes a character like Vijay's masseuse friend Abdul (the inimitable Johnny Walker) looking for customers in a park and creates a lovely little comic gem of a solo number-- with Walker's elbows akimbo and his massage oil in a pair of cruets, he looks as if he planned to turn someone's head into tossed salad. Later Vijay visits a whorehouse where a prostitute is forced to entertain despite the wails of her sick child, and Dutt turns Vijay's sung response ("These alleys, these houses of attraction") into a genuine cry of pain and moral disgust (no narcissism here). The sharp camera angles and lighting (by V.K. Murthy); the gritty imagery (railroad yard, waterfront); the occasional in-joke (Meena at one point reading a "Life" magazine featuring Christ on its front cover) round up Dutt's capacious bag of tricks.

Dutt in a way resembles another master of cinematic bombast, Orson Welles-- like Welles he's a liberal and humanist; like Welles, if you scratch the surface you're likelier to find emotional clichés than a rigorous political philosophy. Like Welles, Dutt cares about the poor and downtrodden, but only in a way that feeds his personal demons (he's on their side because it's more romantic that way). What makes his and Welles' films profound aren't the sentiments but the obsessions working away beneath them-- in Welles' case, his fascination with death and decay, in Dutt's case his anger over the world's hypocrisy. This is why their visual styles are so expressive-- they're covering up not just their political shallowness but a complex knot of emotions they'd rather not reveal (and yet are too great artists not to).

And we're not even enjoying all that the film has to offer, I suspect. The subtitles are serviceable, but if you ignore the translation and focus on the actual words being spoken (or sung)-- if you listen to the rhythms, the sounds, the aural concordances-- you'd suspect that the lyrics (based on the poems of Sahir Ludhianvi, set to the music of S.D. Burman) are as rich in rhyme and meter, as steeped in romance and gothic doom as, say, the poetry of Edgar Allan Poe. Think, in short, of Poe set to playback.

Casablanca is a dinky little melodrama set in a fantasy nowhereland where the problems of three people amount to little more than a hill of beans in this crazy world. Pyaasa is a dinky little melodrama set in present-day Calcutta (shot in actual locations) where the problems of one person amount to the world's most important hill of beans-- such is Dutt's achievement. A great film, absolutely.

(First published in The Brutarian, Spring 2004)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment