Zen and the art of horror filmmaking

The runaway success of Hideo Nakata's Ringu (Ring, 1998) in Manila shows there's an audience for stylish horror out there--the film has been frightening audiences since December, easily outgrossing the poorly made (if more expensive) American remake, with a sequel poised to scare up even more money. Now that we've proven we can appreciate more sophisticated terrors, are we ready for something a little more...well, disturbing?

Thanks to the Japan Foundation we're about to find out. For the past few years the Foundation has been featuring weak comedies and tepid melodramas (though their anime program has been consistently interesting); now they've decided to bring in the big guns. Free, from February 26 to March 21 at Shangri La Cinema, the Cultural Center of the Philippines, and the UP Film Center, is the Eiga Sai 2003 Film Festival, with a focus on Kurosawa Kyoshi (no relation to the legendary director of Seven Samurai).

Kyoshi, along with Nakata, has been described as the "vanguard of Japanese horror"--you might say Kyoshi's latest, Kairo (Pulse, 2001), is his own take on "Ringu."

Kyua (Cure, 1997) begins with a series of murders--a prostitute, a housewife, a police officer among others, killed with, respectively, an iron pipe, a kitchen knife, a revolver. The only common factor among the murders is a deep "X" carved into the chests of the victims; that, and the fact that the murderer is easily caught or hasn't left the scene of the crime at all. Bewildering? As one detective observes, most people expect a pattern in a series of killings; the truth is, most killings don't make sense at all.

That's ironically the most sensible statement anyone makes; the police procedural that takes up the first hour doesn't do much more than add to the confusion of the investigating officers. It's only when they step back from each individual killing that they begin to see: the killings don't have a pattern they have a principle--in fact, they have an entire way of thinking behind them. That's what makes Kyua so different from (and much better than) all other serial killer flicks since, oh, John McNaughton's Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer eight years before.

Kurosawa Kyoshi dabbles in the kind of quiet terror Nakata parlayed into a multinational hit (Kyoshi's film came earlier); if Kyoshi hasn't achieved Nakata's level of box-office success, it may be because he's more uncompromising. Kyoshi's music and sound effects and camerawork are if anything sneakier (the film's final long take is an intricately choreographed picture of normalcy that just might freak you out without knowing exactly why). And unlike Nakata he's able to suggest that the plot inconsistencies are really part of the effect he's trying to create--which may leave you applauding his brilliance, booing his effrontery, or applauding his brilliantly deadpan effrontery.

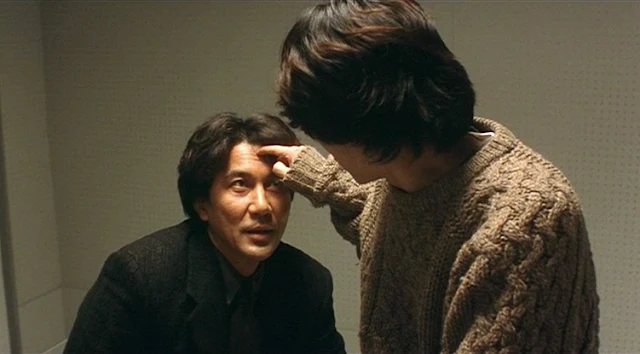

And Kyoshi, unlike Nakata apparently, isn't concerned with merely scaring you (skip this paragraph if you haven't seen the film). Halfway into the picture we meet Mamiya (Masato Hagiwara), the man apparently responsible for the killings; when he meets someone his first pointed question is: "who are you?" Before this Mamiya has the meandering manner of someone without short-term memory, who can't remember where he is or what he said five minutes before; afterwards he takes on the tone of someone altogether more malevolent. I don't think this is (as is later suggested) just a psychological technique; I think it's his way of insisting on the primacy of identity, the importance of a man knowing who he is and what is his ultimate purpose. Mamiya's philosophy is only vaguely glimpsed (the way the most unforgettable images in horror cinema are) but seems to consist of an awareness of the utter void at the center of existence, and of reacting to that void appropriately. Kyoshi's achievement is not in attaching this philosophy to a horror story but in showing us the horror of the philosophy, in a story.

Karisuma (Charisma, 1999) is in some ways a sequel to Kyua; the same actor (Koji Yakusho) again playing a police officer, again faced with strange phenomena. Yakusho's character has been disgraced and dismissed from the police force; he wanders into a forest, where he finds a lonely tree named Charisma, said to be killing the forest with deadly toxins. A power struggle ensues over the tree--some want it cut down, to save the forest; others want it preserved.

Apparently made on a larger budget after Kyua, the film doesn't seem as fine-tuned--the tone swings from deadpan comedy to cold-blooded horror without much sense of control, and at one point Yakusho sits to tell us what the film's all about (a mistake Kyoshi never makes in Kyua). Kyoshi gave the script to the Sundance Institute back in 1992, where it won him a scholarship; the inexperience shows, I think, despite the years between script and finished product...

That said, there are amazing sequences in the film--the tense hostage rescue that ends in the officer's dismissal; the abandoned sanitarium; the vicious slapstick as various factions battle over the tree; the ominous final image (Kyoshi has a talent for unsettling closures). All this photographed in Kyoshi's coolly distant style: no close-ups (except, perversely, to focus on some unimportant detail when you badly want the camera turned elsewhere); mostly long takes emphasizing the everyday texture of the world at large, against which extraordinary horrors might suddenly break through. Again, Kyoshi takes an ostensible story--several groups disputing an ecological issue (to destroy or not destroy a killer tree)--and brings out the inherent philosophy (not to mention comedy and mayhem). This may be the first film ever to treat the act of tree poisoning as an existential process.

Ningen Gokaku (License to Live, 1999) is about a boy that falls into a coma for ten years; when he wakes up he has the body of a grown man, though emotionally still a child. Any other director would've milked the situation for melodrama and many have, but Kurosawa keeps a witty slightly surreal distance; he records in precise clinical style the absurdity of a boy turned young man trying to live the rest of his as-yet unrealized life. Yes, there is pathos in the end--the boy's dilemma calls for nothing less--but Kurosawa earns it honestly, with patiently accumulated details. He approaches tragedy from an oblique angle, looking at the target with sidelong glances; you never hear him coming till he's right behind you, ready to blindside you with a single blow.

If there's any obvious message to the film--I'm only guessing here, I pretend to no definitive answers (and Kyoshi isn't volunteering any)--it may be that life is a fragile and temporary condition, arbitrarily granted, arbitrarily taken away. You waste your time fooling around with junk like abandoned refrigerators at your own risk.

Watching these three films you can't help but wonder if Kyoshi is perhaps in love with death or, more to the point, with the nothingness that seems to lie beyond death. All three deal with this fascination at different levels (personal, social, global), and from different directions (drama, ecological horror-comedy, crime thriller). I had wondered, Ningen Gokaku being my first ever exposure to Kyoshi years before, how he could have ever been slapped with a label more suited to Nakata ("vanguard of Japanese etc., etc."). Having seen the three I think I know why: because he finds the most commonplace situations (yanking at an abandoned refrigerator, digging at tree roots, picking up a kitchen knife) terrifying, and the most terrifying circumstances (the loss of one's youth, of one's soul, of the world) unsettlingly commonplace.

(First printed in Businessworld, 2.28.03)

No comments:

Post a Comment