I heard you make movies

In The Irishman (2019) someone puts a question to Frank Sheeran (Robert De Niro), the same question that is title of Charles Brandt's 2004 book--the same question one might ask of Martin Scorsese with the same innocuousness, and just the hint of something more.

Arguably the question is bullshit--Bill Tonelli in a Slate piece pokes holes in Sheeran's story and on the surface the very premise of the film sounds implausible: an armed Forrest Gump wandering the margins of mob history, delivering boxloads of Browning M2 machine guns for the Bay of Pigs invasion; walking into Umberto's Clam House to shoot 'Crazy' Joe Gallo; walking into an anonymous house in suburban Detroit with gun in hand, right behind Jimmy Hoffa (in Brandt's book Sheehan goes further to claim he delivered three rifles to a pilot days before the Kennedy assassination, and half a million dollars to US Attorney General John Mitchell)?

Tonelli even makes fun of the book's title: "In all of mob literature" he asks, "fictional and factual, has anyone ever uttered such expressions about painting and carpentry?" I wouldn't know, not familiar with mob literature, and what mob cinema I've seen--no.

But it's a hell of a phrase. "I hear you paint houses;" "I hear you make movies"--and I remember a scene in Resident Evil: Retribution where Milla Jovovich hands Michelle Rodriguez a pistol and ties film and violence together with the single throwaway statement "just like a camera: point and shoot."

The film's themes also rope in one of Scorsese's pantheon figures, John Ford, whose late masterwork The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance turned on the phrase: "When the legend becomes fact, print the legend." Ford had a way of making historical accuracy seem irrelevant or at least dull; someone once pointed out that the climactic chase in Stagecoach would have ended sooner if the Apaches had shot the horses. Have no real response to that, save the thought probably doesn't come to mind while actually watching the film.

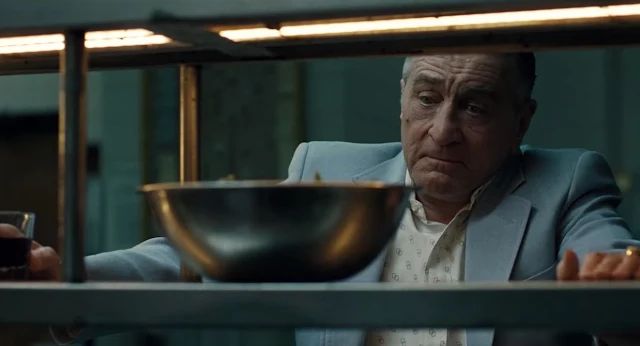

Sheeran doesn't exactly pop out of the screen: this is one of De Niro's more introverted performances, where he plays a lump that if allowed would rather blend into the background--someone who treads lightly but carries a loud .38 Special.

Or so Sheeran says--again we need to take his word with a chunk of salt (Tonelli scoffed at the idea that he ever took a life, though I wonder if the writer ever considered Sheeran's war record). It helps that Scorsese does away with Brandt as a character and has Sheeran face the lens directly as an old man (the camera wandering in past wizened figures tottering on canes and walkers to come upon our protagonist in a wheelchair, lost in his memories).

That image (an old man his memories) starts and ends the film. Sheeran experiences two kinds of flashbacks--one a trip from Philly to Detroit the other the various memories prodded along the way, like birds flushed out of a forest canopy by a train's passage. One the narrative spine the other the narrative meat, the retirement home scenes framing the whole.

Gradually an image forms: of truck driver Sheeran and his chance meeting with Russell Bufalino (Joe Pesci, reportedly coaxed out of retirement after being asked fifty times, terrific as always), of his later meeting with James Riddle Hoffa (Al Pacino) and their developing affection for each other.

Sheeran and Hoffa recall Scorsese's earlier autobiographical Mean Streets with Hoffa as Johnny Boy, the irrepressible Id to De Niro's Sheeran as dutiful Charlie (who--following Mean Streets' schema--represents the director's cringing conscious-stricken self). De Niro as the original Johnny Boy lit the screen with his unpredictably hilarious-yet-horrifying antics; as this film's Charlie he's if anything better, the staunch spear-bearer of first Russell and later Jimmy Hoffa. Call Sheeran a man of faith, the faith established by an ancient organization with laws and secrecy and wide-reaching influence; call the film a test of Sheeran's faith versus his family (with his daughter Peggy--Anna Paquin as an adult, the haunting Lucy Gallina as a child*--standing as witness), versus his friend Hoffa.

*(As for the whole brouhaha about Paquin's character's relative silence--there's some point to the Bechdel test, but the impact of Peggy depends mainly on the idea that she stands aside watching what's going on and keeping everything to herself, only speaking up (as an adult at least) when it most mattered. Like her father she sees but is silent; like her father she remembers, feels, judges.**)

**(As for Peggy's judgment I'm guessing she keeps arms' distance from her father and Russell because they're killers; Hoffa while egotistical and corrupt is not--at least not directly, as far as we know. It's the stink of blood that makes the difference.)

The latter half of the film plays out like The Last Temptation of Frank or, going back even further, Mean Streets: Detroit--the rising power figure betrayed by his Judas. Frank/De Niro as Judas/Charlie/Scorsese marks the progress of his betrayal as near-imperceptible tics on the face, fissures in a supposedly professional mask, the grim line of a mouth warping gradually into a grimace.

Is Scorsese replaying his greatest hits? I'd say he's reviewing them slowed down and distorted, turning them over in his head in the hope possibly vain of making sense of what he had wrought wrote rote. His operatic style dialed down to a whisper his visual brio reduced to a simmer, he seems subdued even humbled when confronting what may be his Frank's Jesus' Charlie's final adversary. If as detractors say this is yet another of Scorsese's gangster flicks it has the look and feel of a final Scorsese gangster flick--his last word on the subject. Any further films would smack of redundancy.

Saying 'dialed down' doesn't mean 'totally absent.' The opening and the barber shop scene show Scorsese still has spark, just not front and center; the Gallo hit is a marvel of blinking bright reds and whitewashed walls drenched in sickly green neons. The director has also taken to perching the camera from on high to look down on a street corner or hallway intersection, suggesting a dramatic turning point.

Sound may be the film's most innovative feature: Sheeran's offscreen narration opens the picture and suddenly the man's lips move, continuing his train of thought; the scoring is relatively subdued, with long stretches of quotidian life punctuated mostly by the clink of silverware or traffic hum or occasional bird call; Sheeran on the phone mutters reassurance to a distressed Jo Hoffa (Welker White, her voice muffled so that emotion and not specific words are audible), the sheer hypocrisy of his words registering like gunshot wounds on his wincing face.

Not a perfect picture: the digital de-aging looks grotesque, actually even more grotesque on the big screen with De Niro's and Pesci's faces a boiled lobster red, their hunched bodies walking slowly carefully as if they were in their frail seventies (which they are)--watching the film on streaming Netflix has apparently corrected the offputting red, though the old-man movements remain. I remember how in Leone's Once Upon a Time in America Scott Tiler's performance as the young Noodles dovetailed so lyrically into De Niro's, and wonder why Scorsese couldn't cast accordingly. Also wonder if Scorsese couldn't have inserted a little more skepticism about the veracity of Sheeran's claims, suggest a little more loudly that the man's memory is unreliable--possibly De Niro (who produced) and Scorsese bought Sheeran's story hook line and sinker, only pivoting in interviews (emotional truth over historical) in response to Tonelli's article.

O and the titles informing us of the various mobsters' fates ('shot in the head, 1980;' 'killed, 1979')--what could have happened between 1979 to 1980 that killed all these mobsters? One of the film's biggest laughs occurs when we learn that Tony Jack (well-liked by all) died of natural causes in 2001.

The final fifty-plus minutes (skip this and the next paragraph if you haven't seen the film!) recalls Father Rodrigues' odyssey as a changed man moving through a more accommodating Japan in Silence--what to do with yourself when you've won the one thing you desire (the cessation of others' suffering) at the price of the one thing you value (your faith)? Rodrigues' struggle is frightening in its way--he can't utter even a whisper of dissent--but Sheeran in total freedom and with only passing interest from law enforcers (a pair of visiting federal agents, asking him to come clean) learns an additional lesson: with the passage of enough time no one cares. People die people forget things change. Rodrigues faced the absolute terror of totalitarian repression for the rest of his long life; Sheeran faced the absolute despair of invincible indifference for the rest of his.

I find Tonelli's points believable, including one that even Tonelli concedes: Sheeran must have been sitting in the car that drove Hoffa to his death otherwise Hoffa would have never climbed in. Sheeran was involved, however tangentially, likely knew what was going on. All this--Sheeran shooting Hoffa, shooting Gallo, even delivering guns for the Bay of Pigs invasion--is his way of improving his stature that his fall might be all the greater, confessing imaginary crimes to give scope and scale to his real central sin: betraying a friend who trusted him. As with Willem Dafoe's Jesus, much of the three hours might be taking place inside Sheeran's guilt-wracked skull, the ultimate prison cell and torture chamber.

John Ford once appeared before the Director's Guild to say "My name's John Ford. I make Westerns." The matter-of-fact statement neatly sums up what the man was about the way this film pretty much sums up what Scorsese's about (and as I say that titles come to mind contradicting the assertion: Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore; Kundun; Hugo). A terrific work I think, the best American production of the year--which I think is true even if you didn't like the picture.

First published in Businessworld 12.6.19

In The Irishman (2019) someone puts a question to Frank Sheeran (Robert De Niro), the same question that is title of Charles Brandt's 2004 book--the same question one might ask of Martin Scorsese with the same innocuousness, and just the hint of something more.

Arguably the question is bullshit--Bill Tonelli in a Slate piece pokes holes in Sheeran's story and on the surface the very premise of the film sounds implausible: an armed Forrest Gump wandering the margins of mob history, delivering boxloads of Browning M2 machine guns for the Bay of Pigs invasion; walking into Umberto's Clam House to shoot 'Crazy' Joe Gallo; walking into an anonymous house in suburban Detroit with gun in hand, right behind Jimmy Hoffa (in Brandt's book Sheehan goes further to claim he delivered three rifles to a pilot days before the Kennedy assassination, and half a million dollars to US Attorney General John Mitchell)?

Tonelli even makes fun of the book's title: "In all of mob literature" he asks, "fictional and factual, has anyone ever uttered such expressions about painting and carpentry?" I wouldn't know, not familiar with mob literature, and what mob cinema I've seen--no.

But it's a hell of a phrase. "I hear you paint houses;" "I hear you make movies"--and I remember a scene in Resident Evil: Retribution where Milla Jovovich hands Michelle Rodriguez a pistol and ties film and violence together with the single throwaway statement "just like a camera: point and shoot."

The film's themes also rope in one of Scorsese's pantheon figures, John Ford, whose late masterwork The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance turned on the phrase: "When the legend becomes fact, print the legend." Ford had a way of making historical accuracy seem irrelevant or at least dull; someone once pointed out that the climactic chase in Stagecoach would have ended sooner if the Apaches had shot the horses. Have no real response to that, save the thought probably doesn't come to mind while actually watching the film.

Sheeran doesn't exactly pop out of the screen: this is one of De Niro's more introverted performances, where he plays a lump that if allowed would rather blend into the background--someone who treads lightly but carries a loud .38 Special.

Or so Sheeran says--again we need to take his word with a chunk of salt (Tonelli scoffed at the idea that he ever took a life, though I wonder if the writer ever considered Sheeran's war record). It helps that Scorsese does away with Brandt as a character and has Sheeran face the lens directly as an old man (the camera wandering in past wizened figures tottering on canes and walkers to come upon our protagonist in a wheelchair, lost in his memories).

That image (an old man his memories) starts and ends the film. Sheeran experiences two kinds of flashbacks--one a trip from Philly to Detroit the other the various memories prodded along the way, like birds flushed out of a forest canopy by a train's passage. One the narrative spine the other the narrative meat, the retirement home scenes framing the whole.

Gradually an image forms: of truck driver Sheeran and his chance meeting with Russell Bufalino (Joe Pesci, reportedly coaxed out of retirement after being asked fifty times, terrific as always), of his later meeting with James Riddle Hoffa (Al Pacino) and their developing affection for each other.

Sheeran and Hoffa recall Scorsese's earlier autobiographical Mean Streets with Hoffa as Johnny Boy, the irrepressible Id to De Niro's Sheeran as dutiful Charlie (who--following Mean Streets' schema--represents the director's cringing conscious-stricken self). De Niro as the original Johnny Boy lit the screen with his unpredictably hilarious-yet-horrifying antics; as this film's Charlie he's if anything better, the staunch spear-bearer of first Russell and later Jimmy Hoffa. Call Sheeran a man of faith, the faith established by an ancient organization with laws and secrecy and wide-reaching influence; call the film a test of Sheeran's faith versus his family (with his daughter Peggy--Anna Paquin as an adult, the haunting Lucy Gallina as a child*--standing as witness), versus his friend Hoffa.

*(As for the whole brouhaha about Paquin's character's relative silence--there's some point to the Bechdel test, but the impact of Peggy depends mainly on the idea that she stands aside watching what's going on and keeping everything to herself, only speaking up (as an adult at least) when it most mattered. Like her father she sees but is silent; like her father she remembers, feels, judges.**)

**(As for Peggy's judgment I'm guessing she keeps arms' distance from her father and Russell because they're killers; Hoffa while egotistical and corrupt is not--at least not directly, as far as we know. It's the stink of blood that makes the difference.)

The latter half of the film plays out like The Last Temptation of Frank or, going back even further, Mean Streets: Detroit--the rising power figure betrayed by his Judas. Frank/De Niro as Judas/Charlie/Scorsese marks the progress of his betrayal as near-imperceptible tics on the face, fissures in a supposedly professional mask, the grim line of a mouth warping gradually into a grimace.

Is Scorsese replaying his greatest hits? I'd say he's reviewing them slowed down and distorted, turning them over in his head in the hope possibly vain of making sense of what he had wrought wrote rote. His operatic style dialed down to a whisper his visual brio reduced to a simmer, he seems subdued even humbled when confronting what may be his Frank's Jesus' Charlie's final adversary. If as detractors say this is yet another of Scorsese's gangster flicks it has the look and feel of a final Scorsese gangster flick--his last word on the subject. Any further films would smack of redundancy.

Saying 'dialed down' doesn't mean 'totally absent.' The opening and the barber shop scene show Scorsese still has spark, just not front and center; the Gallo hit is a marvel of blinking bright reds and whitewashed walls drenched in sickly green neons. The director has also taken to perching the camera from on high to look down on a street corner or hallway intersection, suggesting a dramatic turning point.

Sound may be the film's most innovative feature: Sheeran's offscreen narration opens the picture and suddenly the man's lips move, continuing his train of thought; the scoring is relatively subdued, with long stretches of quotidian life punctuated mostly by the clink of silverware or traffic hum or occasional bird call; Sheeran on the phone mutters reassurance to a distressed Jo Hoffa (Welker White, her voice muffled so that emotion and not specific words are audible), the sheer hypocrisy of his words registering like gunshot wounds on his wincing face.

Not a perfect picture: the digital de-aging looks grotesque, actually even more grotesque on the big screen with De Niro's and Pesci's faces a boiled lobster red, their hunched bodies walking slowly carefully as if they were in their frail seventies (which they are)--watching the film on streaming Netflix has apparently corrected the offputting red, though the old-man movements remain. I remember how in Leone's Once Upon a Time in America Scott Tiler's performance as the young Noodles dovetailed so lyrically into De Niro's, and wonder why Scorsese couldn't cast accordingly. Also wonder if Scorsese couldn't have inserted a little more skepticism about the veracity of Sheeran's claims, suggest a little more loudly that the man's memory is unreliable--possibly De Niro (who produced) and Scorsese bought Sheeran's story hook line and sinker, only pivoting in interviews (emotional truth over historical) in response to Tonelli's article.

O and the titles informing us of the various mobsters' fates ('shot in the head, 1980;' 'killed, 1979')--what could have happened between 1979 to 1980 that killed all these mobsters? One of the film's biggest laughs occurs when we learn that Tony Jack (well-liked by all) died of natural causes in 2001.

The final fifty-plus minutes (skip this and the next paragraph if you haven't seen the film!) recalls Father Rodrigues' odyssey as a changed man moving through a more accommodating Japan in Silence--what to do with yourself when you've won the one thing you desire (the cessation of others' suffering) at the price of the one thing you value (your faith)? Rodrigues' struggle is frightening in its way--he can't utter even a whisper of dissent--but Sheeran in total freedom and with only passing interest from law enforcers (a pair of visiting federal agents, asking him to come clean) learns an additional lesson: with the passage of enough time no one cares. People die people forget things change. Rodrigues faced the absolute terror of totalitarian repression for the rest of his long life; Sheeran faced the absolute despair of invincible indifference for the rest of his.

I find Tonelli's points believable, including one that even Tonelli concedes: Sheeran must have been sitting in the car that drove Hoffa to his death otherwise Hoffa would have never climbed in. Sheeran was involved, however tangentially, likely knew what was going on. All this--Sheeran shooting Hoffa, shooting Gallo, even delivering guns for the Bay of Pigs invasion--is his way of improving his stature that his fall might be all the greater, confessing imaginary crimes to give scope and scale to his real central sin: betraying a friend who trusted him. As with Willem Dafoe's Jesus, much of the three hours might be taking place inside Sheeran's guilt-wracked skull, the ultimate prison cell and torture chamber.

John Ford once appeared before the Director's Guild to say "My name's John Ford. I make Westerns." The matter-of-fact statement neatly sums up what the man was about the way this film pretty much sums up what Scorsese's about (and as I say that titles come to mind contradicting the assertion: Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore; Kundun; Hugo). A terrific work I think, the best American production of the year--which I think is true even if you didn't like the picture.

First published in Businessworld 12.6.19

2 comments:

Thoughtful a degree. For like so many other critics you imagine Marty to be making the same gangster film over and over again. "Mean Streets"? Why didn't you g all the way back to "It's Not Jusy You, Murray"? (It can be seen on YouTube, btw) "Menn Streets" is about wiseguys wannabes loitering on the edge f crime. "Goodfellas" is about the thrill of crime as practiced by middle-class "family men." "Casino" is about a gambling hustler who having hit the jackpot by marrying a casino boss can't deal with her own success because she hates herself. So she sets bout engineering a slow motion suicide (ie. drugs and James Woods) "The Departed" is about a cop who I filtrates the mob. "The Irishman" is a historical sidebar relayed though the untrustworthy memories of a dying old man.

Yes this WILL be on "The Final"

I think he draws on his previous films. But what filmmaker doesn't, and isn't Ozu the ultimate filmmaker making variations on a number of basic themes, to the point of achieving great art (with Bach as his musical equivalent?)? I don't see anything wrong with variations on a theme, and this one goes further arguably than even Silence on exploring a man's longterm lifetime reaction to the consequences of his betrayal.

Post a Comment