Caged

John Fowles' debut novel The Collector has been adapted several times for theater stage and big screen, most notably by William Wyler, later by Mike de Leon for a 1986 feature--Bilanggo sa Dilim (Prisoner in the Dark) shot on video.

Comparing the two productions can be instructive: Wyler's is a smoothly executed Hollywood production with a fairly gripping finale; de Leon's feels more subdued, understated, unnervingly autobiographical.

Wyler's film enjoys the resources of a mainstream studio: exteriors shot at a genuine English manor, interiors on elaborately constructed sets including what's supposed to be a vast underground chapel--a basement where Freddie (Terence Stamp) hold art student Miranda (Samantha Eggar) captive in relative comfort if not luxury.

De Leon's Eddie (Joel Torre) also owns a large if less antiquated house--a faintly Spanish casa--with a more spare look where he plans to hold his Miranda (here called Marissa (Cherie Gil)). Not quite as impressive till I remember the Bates Motel, where Hitchcock recreated the antiseptic whiteness of an American motor court and spattered it with gore; the feeling of desecration is startling, almost shocking. De Leon's camera glides alongside the house's deadpan walls and you sense the secrets they are not telling.

Maurice Jarre's symphonic score for The Collector (occasionally borrowing from his work for Lawrence) mickeymouses the action (stalking music for when Freddie stalks Miranda, suspense music for when Miranda attempts escape) in a way that's often unintentionally hilarious; later Wyler drops the score and just gives us gasps and grunts as captor and captive struggle for control which is much better--but you still have to sit through that appalling first half. De Leon opts for a minimalist approach--mostly an ominous synthesizer thrum and the occasional dark melody--and achieves more with less (if anything I'd say much of the atmosphere is provided by Jun Lantonio's music).

The Collector features Stamp and Eggar, Bilanggo Torre and Gil; Eggar and Gil show skill in playing their respective characters' mix of strength and vulnerability, though Gil's Marissa being a celebrity model/fashion designer is necessarily the more sophisticated woman, who easily intimidates Torre's Eddie. Stamp I believe is miscast as Freddie--one look at him with his cool bluegrey eyes and unearthly gaze and you know he's strange. Torre channels the 'shy sheltered boy from a wealthy family' look he patented when he debuted in Oro Plata Mata--seemingly overmatched till his eyes acquire a sullen ugly glare that can flare up into anger even violence. Stamp puts you on guard from the start; Torre inspires a sneaking sympathy until he suddenly emphatically doesn't.

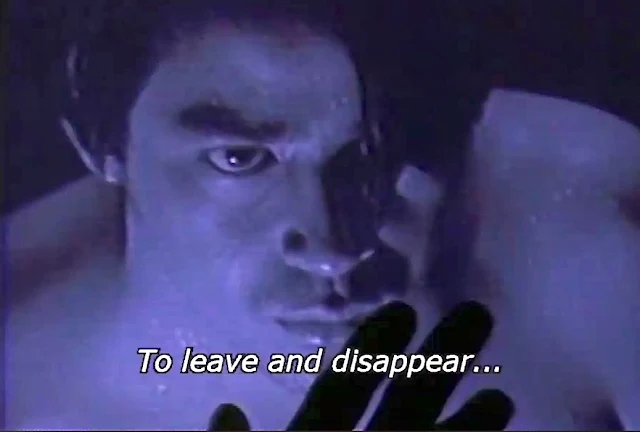

Wyler's standard studio style is if anything blander than usual, mostly master shots from a medium distance. Stands him in good stead when he suddenly departs from formula--the occasional low-angle of Stamp glaring out from a darkened corner, or the climactic struggle in rain, partly shot handheld, at ground level. But there's a world of difference between Wyler's idea of claustrophobic and De Leon's--the blank walls punctuated by heavy doors, the giant closeups of faces, the tight shot on a pair of hands bound with rope. Enigmatic dream sequences--where De Leon experiments with color filters and visible video grain (did he see Antonioni's The Mystery of Oberwald?)--hew closer to the spirit of Fowles' novel (with its share of nocturnal visions) than Wyler's more straightforward adaptation.

De Leon's most radical revisions are found in the character of Eddie ('Freddie' with a consonant excised). Where Freddie (Frederick in the novel) is a butterfly collector--collecting beauty, as Miranda once accused him of doing, by killing it--Eddie is a photographer, a more harmless-sounding occupation till we remember that Mark Lewis in Michael Powell's Peeping Tom is also a photographer/filmmaker/psychopath voyeur. Where Freddie is an anonymous bank teller who suddenly wins a lottery (giving him the means to buy his mansion) Eddie is already rich, with money left to him by his dead father and mysteriously absent mother ("Can we please not talk about her?" he at one point asks). Can rich folk be as socially awkward or alienated as Eddie? Can rich folk prey on their so-called 'social inferiors?' Yes (speaking from personal experience--more easily I submit than the middle or lower classes) and absolutely yes. Here I believe De Leon actually improves on Fowles; if recent Philippine history tells us anything (as De Leon suggests here, more explicitly in his latest feature Citizen Jake) powerful political families are the metastasizing cancer of society, and De Leon does not seem to exclude himself in that blanket condemnation.

Towards the end of Wyler's film Freddie declares: "I made a mistake" and muses that he should have aimed lower, perhaps picked someone closer to his class level (he's last seen stalking a nurse). De Leon's Eddie is the smarter specimen; instead of overreaching he starts with more malleable material in the form of Margie (Rio Locsin), a college student who works part time as a prostitute. Fowles' novel is told from two points of view: first Frederick's, then Miranda's, then again Frederick's; Wyler's film does away with that structure, alas (it was Fowles' most interesting conceit, building empathy for both predator and prey). De Leon not only restores the sense of two voices in violent opposition (Eddie's and Marissa's) he adds a third voice, Margie's--Marissa finds her note folded up and hidden away in the corner of a jewelry box, and reads her story.

We don't get much of Locsin's Margie; she's onscreen for brief minutes at most. But she's a crucial piece missing I think in Fowles' overall design--where he had in Freddie a working-class predator kidnapping Miranda, a middle-class intellectual (father's a doctor, but with no real money) with Eddie we have a member of the upper class seizing and abusing a member of the lower. It's a withering sight: she's ardent then terrified then submissive then ultimately resigned; at one point she actually speculates that perhaps Lito (the name Eddie gives her) might be the answer to her prayers. Imagine a girl so poor she entertains the idea of life with a budding serial killer as a viable alternative--

De Leon's film differs from Wyler's differs again from Fowles' novel in the finale (Skip the rest of this paragraph if you haven't seen or read all three!). One might accuse him of actually softening Fowles' chilling conclusion, to which I have three responses: 1) We have Fowles' original ending, which De Leon appends to Margie's story (and suggested by repeated images of Eddie digging a grave (shades of Dreyer's Vampyr?))--Marissa's kidnapping is in effect sequel to Eddie's first adventure; 2) Marissa's / Miranda's assault on Eddie / Frederick should really be the end of the situation; I don't quite buy Miranda's failure to finish Freddie off (maybe it's the times--with today's collectors you feel you should strike back viciously, ruthlessly) nor do I consider pneumonia a fitting end for such a vital character (Random ordinary bacteria? Really?); and 3) if as I suggest Eddie's character is semi-autobiographical, then I suspect De Leon (despite all his attempts to make the action more realistic) has chosen a not more logical but more appropriate fate: death. Eddie has a death wish; wants nothing more nothing less than peace--to be left alone for always. Marissa accuses Eddie of being the real prisoner, a captive to his desires; if the final fadeout means what I think it means then Eddie is freed--a small measure of comfort the filmmaker grants this most uncomfortable (and possibly personal) of his creations.

Throughout the film we see reflections recordings remembrances of various characters. Marissa's face we see in newspaper photos and magazine covers, the multiplicity of images suggesting her pervasive presence in society; by way of contrast Margie, a social nobody, exists only in Eddie's recordings and photographs and haunted memories--a life almost fully eradicated completely silenced if it wasn't for her hidden note. Eddie's mother is an even more enigmatic figure--when we finally see her it's in a dream sequence where she strokes Eddie's head as he lays across her lap; the camera pans up and there's an empty space where her own head should be.

Near film's end we see Eddie touching his own image on a video screen. A moment of self-absorption or self-accusation? De Leon isn't saying; he leaves the image on the screen for us to look at and ponder.

First published in Businessworld 7.6.18

2 comments:

Since Filipino movie producers are focusing more on money instead of value, movies like this are gone.

It's gotten ghettoized. Special festivals like To Farm and Cinema One Originals do original and even experimental productions. But yes the mainstream has become if anything even more commercial.

Post a Comment