Horrorshow

The horror genre is experiencing some kind of renaissance, interesting premises hurled at our faces right left fore aft, with varying degrees of success. Leo Gabriadze's Unfriended (2015) had a brilliant idea--tell its story entirely through a computer's many popup screens--but dissolves quickly in a sea of tired cliches, of the 'found footage' variety. Jennifer Kent's The Babadook (2014) starts out strong as a harrowing portrait of a single mother and her troubled child, but doesn't seem to know how to direct its focus properly (who's in danger, who's the danger: mother or child?). Genre outlier David Robert Mitchell's It Follows takes its cue from John Carpenter's gliding-camera sense of menace to record the constant approach of a vengeful shape-changing wraith, only to stage a silly swimming pool climax that undercuts much of what went before (to its credit the victimized teenagers are fascinating fatalists--if anyone can survive or even thrive under such circumstances they probably would).

Best of the lot is relative old-timer M. Night Shyamalan's The Visit, who uses the aforementioned found-footage cliches--done with a more stylish camera than is standard for the genre--to tell the touching story of a fragmented family's attempt to pull together. The plot's all kinds of nonsense--if you look too closely it immediately falls apart--but the movie's emotional thread, at least, feels strong.

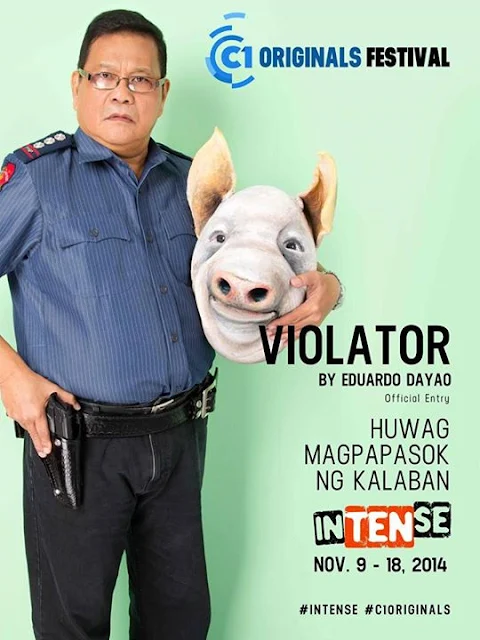

Eduardo Dayao's Violator doesn't really start out with a strong premise so much as with a series of vignettes, one more creepily enigmatic than the next--a police officer learns of his impending mortality; co-workers stand on a rooftop, gazing at the city below (this doesn't end well); another pair--colleagues? lovers? old friends?--lug gasoline jerrycans across a rocky landscape; a couple has sex, quarrels, and when the father turns to leave faces his child's unspoken inexplicable fury.

The brilliant first half is a loose-linked lopped-off cross-section of Metro Manilan middle-class society from police officer to schoolteacher to office worker to gang member, their predicaments quickly sketched out, their circumstances deftly hinted at. Perhaps most unsettling is a Ringu-style videotape about a religious cult, complete with guitar-led singing and baptismal rituals involving hooded acolytes floating in a near-empty swimming pool. The video sets the tone for the film's latter half: a sense of gathering unease, of half-glimpsed figures and apocalyptic omens, of an intimidating quantity of dark water.

What recent horrors seem to have in common is this ability to come up with a good even great concept then not knowing what to do next. Dayao attempts to sidestep the problem by starting vague then zeroes in on a single narrative, one that brings together some if not all of the earlier characters (a few are mentioned in passing).

Does it work? Some critics prefer the ambiguity of the vignettes; I'm of the school of thought that a belatedly applied unifying narrative can work too, if the story is wild or intriguing enough.

Hence the police station--appropriately named Precinct 13--where the dying officer, his men, and a handful of civilians face an end-of-the-world deluge, an encroaching band of aforementioned cultists, their own inner demons. John Carpenter channeling Howard Hawks meets Kurosawa Kiyoshi, with a dash of Hideo Nakata--if that's not interesting I don't know what is.

It helps that Dayao seems to be trying to get away with filming on as few bulbs as photographically possible ("if you don't have the money to properly light a movie" he seems to be telling us, "let the audiences' imagination do the work for you."). Maybe his most striking effect--for those who actually notice--is to approximate the kind of visually obfuscating fast-cutting often found in standard-issue horrors without actually doing any fast cuts.

The links and allusions Dayao wants you to make aren't exactly clear, which I suspect points to another of his working principles ("if you don't have the money to properly execute a script--"). The folks trapped in the station are of the Hawksian variety--tough, profane, not without a sense of humor or sense of irony. They don't have much to work on plotwise, but that's part of the horror--reasonably intelligent, reasonably strong-willed folks trying to deal with ordinary life and what they gradually come to suspect is the end of the world, with little to hold on to, much less work on, and it's overwhelming them--slowly, gradually, like a rising flood.

It's a good cast--action veteran Victor Neri and relative newcomer Anthony Falcon (Agent X-44!) make for an amusing pair of cops; Timothy Mabalot as Nathan Winston Payumo is an unlikely agent of the Apocalypse--but it's his very unlikeliness along with Dayao's deft framing and lighting of his oh so young face (complete with diabolical shiteater grin)--that makes the chills surprisingly effective.

It's a good cast--action veteran Victor Neri and relative newcomer Anthony Falcon (Agent X-44!) make for an amusing pair of cops; Timothy Mabalot as Nathan Winston Payumo is an unlikely agent of the Apocalypse--but it's his very unlikeliness along with Dayao's deft framing and lighting of his oh so young face (complete with diabolical shiteater grin)--that makes the chills surprisingly effective.But the film really belongs to the cast's two elders. I don't find the backstory driving Andy Bais' Mang Vic persuasive, but Bais plays the role with fish-eyed Takashi Shimura-like intensity and damn if you don't end up buying what he has to sell anyway, especially when all hell breaks literally loose. Joel Lamangan's Police Chief Alano is the weary wary heart of the film: he's doomed even before the film begins and knows it and somehow finds the strength and courage to endure.

Which may be the most overt takeaway from this most oblique and elliptical of horrors, easily the best I've seen from the genre in recent years: we're all done, doomed, damned yes, but sometimes we manage to endure.

The film was screened for the Cinema One Originals Festival

First published in Businessworld 11.13.15

No comments:

Post a Comment