Sunday, October 27, 2013

The Bride of Frankenstein (James Whale, 1935)

(For Halloween, an old article)

Father of the Bride

I remember seeing this years ago on a Betamax tape, right after seeing the original (I had the films taped off HBO, way back when the channel was new). Frankenstein impressed me with one scene, where the good doctor (Colin Clive) exposes The Creature (the indelible Boris Karloff) to sunlight, and The Creature gropes helplessly, trying to touch the unreachable source of warmth and brightness; the rest of the picture looked cheaply done, with an ending I thought particularly disappointing, the extras running up what obviously was a soundstage set to surround the Creature, and The Creature tossing what patently looked like a dummy off the top of the windmill he was trapped in, before burning to death.

Which meant I wasn't in a good mood when I got to see Bride. The opening scene with Mary Shelley (Elsa Lanchester) spinning off a new story to Lord Byron and her husband already struck a wrong note--felt like a feeble attempt at justifying a sequel. Dr. Pretorious's homunculi I thought silly--Dr. Frankenstein's stitched-together monster looked obsolete compared to those perfect (if tiny) creatures, making me wonder why Pretorious would bother asking the doctor for help at all (they were to combine Pretorious' black arts with Frankenstein's resurrection techniques to create a "a man-made race"). The rest of the film was more bizarre than bloodcurdling, down to the Bride's flowing robes and daintily birdlike gestures. I don't really understand it at all, at the tender age of (I'm guessing) twelve or so.

Viewing it so many decades later, when I finally understood the concept of 'tongue in cheek,' I was ready to consider it one of the greatest horror films ever made.

Greatest? Why yes; any cheap scare flick from The Exorcist on down can make you jump out of your seat. A great horror needn't be disgusting either--Eli Roth fulfills that particular need on a regular basis, and frankly the returns from all the prosthetics and camera-fu and digital effects (the latter an invention I suspect of the Devil) has been swiftly diminishing, especially in the last few years. If horror at all has a future, it's in the retro minimalism of Ti West, or the exuberant comedy of Sam Raimi, or the chill philosophical musings of Kurosawa Kiyoshi (who I suspect has been moving beyond the genre--if he hasn't left already--in his recent work). In my book a truly great horror has to do far more than simply scare.

James Whale, director of the original monster hit, held out for four years till Universal Studio executive Carl Laemmle gave him complete artistic freedom, a substantially bigger budget (Over $400,000, compared to the original's $262,000), and a whole new team to create a more lush, more luxurious film. Whale didn't want to do a mere sequel; he wanted to go beyond what the original was trying to say--to, in effect, say a few things of his own.

The prologue with Mary Shelley makes more sense now--it's as if Whale were saying "we all know Shelley didn't write a sequel, but let's pretend, shall we…?" The film's true tone is established by a quick scene: the father of the little murdered girl in the first film walks through the smoking ruins of the windmill and promptly falls into an underground cavern; The Creature drowns the father and, when the mother grabs at an outstretched hand thinking it's her husband, drags her into the cavern as well. In the original this would have been an occasion for pure dismay, but here Whale adopts a kind of breezy heartlessness, playing the scene as dark slapstick: you don't know whether to laugh or cry out, and caught between two conflicting emotions can't help but think: "hello--here is something new."

A lot of ink's been spilled over the role of Pretorious: he's been described as "nurturing mother" to Frankenstein's "creative father"--a same-sex couple with their unconventionally engendered (Adopted? Artificially inseminated? Cloned?) child. It's also been pointed out that Pretorious' name is mentioned several times before he actually appears, the way you need to say the Devil's name three times before he appears (Whale shows us a Devil homunculus--a prized specimen from the doctor's collection--to which Pretorious remarks: "There's a certain resemblance to me, don't you think, or do I flatter myself?"). Pretorious, deliciously played by the gay (like Whale himself) Ernest Thesiger, is the life of this party, supplying much of the wit and winking, self-conscious commentary. Clive's Frankenstein is straight Faust to Thesiger's bent Mephisto, the latter's homunculi explained away as being more black magic than science; the Creature everyone fears is actually more a hapless victim caught in the struggle between human and demonic seducer.

Speaking of victim, I'd have thought the scene between The Creature and the blind man (O. P. Heggie), partly derived from Shelley's novel, would have succumbed to the merciless lampooning of Mel Brooks' Young Frankenstein--loved this parody for years. But viewing the original with fresh eyes I realized that while Whale may have intended something satiric--the pious music in the background sounds halfway vampish already--what actually unfolds is surprisingly, well, straight. Again the relationship between Creature and blind man has been seen as a metaphor for same-sex union, which I can buy, but which I also think transcends the metaphor, as it transcends the mosquito-whine music: this is Whale's genuinely felt plea to recognize The Creature's loneliness, a loneliness we've all shared at one point or another, to recognize the possibility of great affection, of true love--suddenly found, not necessarily sexual--between two men. I'd heard about the film being sophisticated horror satire; I never expected it to be moving as well.

And still this fits into Whale's overall scheme, because a satire that holds nothing sacred is simple nihilism, but a satire that can take at least one thing seriously--a satire that has (that unfashionable term) heart--is making a point. It doesn't just flail away at all directions; it plants its feet on some kind of moral ground and sinks its teeth into the meat of its target (you need feet on the ground for traction). Brooks' comedy is marvelous fun (particularly Gene Hackman's cheerfully blind elder), but Whale's original has real dramatic power.

That's about it, except I'd like to note that the Bride (Elsa Lanchester, who also plays Mary Shelly--unemphasized incestuous relationship there) is dressed in resplendent white, like a virgin meant for a grand wedding, but the whole affair looks more like an unholy cross between a masked ball and a town fiesta, complete with the Devil's own collection of laboratory fireworks. The Bride's response to The Creature is startling, the same time it feels inevitable--despite all the preparation and struggle and sweat, can you really guarantee that a woman will agree to bond just like that?

And yet it might be argued that The Creature needed the humiliation--needed the rending apart of the cocoon of lust and anger and hate he has woven defensively around himself. The Bride's rejection has shaken The Creature out of his self-pity; now he is free to learn one more important life lesson, complete one more step in his growth as a human being.

The line "you live…you stay!" grants The Creature the status of a fully human being, capable of rendering moral judgment. Funny how The Creature addresses "father" and "mother"--Frankenstein is known mostly through his absences; if he reacts to the Creature it is usually with horror. Pretorious treats the poor brute better--invites him to share meat and drink and a good smoke and (more importantly) recognizes a fellow freak. Yet The Creature speaks kindly to Frankenstein and witheringly to Pretorious--why?

Because (I think) The Creature realizes that Frankenstein, while a terrible father, struggles with something Pretorious lacks--a conscience, a sense of morality. The Creature respects that struggle, maybe even (despite past abuse) loves the doctor for his struggle, the same time he recognizes that Pretorious despite his amiability is evil. Whale's Creature is like a child who, because of his experiences and despite his sufferings, learns the difference between good and evil, right and wrong. I'd frankly be proud to have raised someone like that.

(First published in Menzone Magazine, October, 2004; modified and posted here 10.27.06)

Wednesday, October 23, 2013

Prisoners (Denis Villeneuve), Carrie (Kimberly Peirce); Machete Kills (Robert Rodriguez, 2013); Captain Phillips (Paul Greengrass, 2013); The Scarlet Letter (Victor Sjostrom, 1926)

(Needless to say, ALL the films mentioned are discussed in detail, including story, plot twists, and ending)

Pray for the best

Denis Villeneuve's Prisoners is a nice example of the airless, minimalist art thriller, set in the rather limited and overfamiliar genre of the child abduction/serial killer flick.

Mind you, there's plenty to like: the generally excellent cast (Paul Dano as mentally challenged Alex Jones and Melissa Leo as his heroically stoic Aunt Holly stand out; Maria Bello is sadly wasted as a cliche of a distressed housewife, confined to bed in a drugged-out stupor); Roger Deakin's bleak cinematography (with Georgia's constant downpour doubling for the wet autumns and sleety winters of Pennsylvania); Villeneuve's understated way of generating suspense quietly, with a minimum of fuss.

I'm less crazy about the script. For all its grimness Prisoners is an ultimately comforting film despite (or perhaps because of) its talk of mazes and mysteries; even someone's statement--that the maze found in a medallion didn't have a solution ("I know, I've tried")--is the kind of declaration of hopelessness you hear just before the dawn. Too many smart guesses solving too many puzzles downgrades one's regard for the film from an eloquent statement on the human condition to an entertainment, nicely made, a couple of steps above NCIS or Law and Order.

Even the moral ambiguity seems neatly parceled out: Hugh Jackman plays Keller Dover, a small business entrepreneur, devout Christian (is he Catholic? It's not made clear), and well-organized survivalist; when his daughter is taken the law requires that he sit still and wait while the police do their job but his can-do, by-the-bootstraps ethos ("Pray for the best, prepare for the worst") demands that he do something--so he does. The resulting scenario is the kind of cobbled-together 'what-if' situation favored by pro-torture advocates (what if your child was in danger?). The next-door neighbors (Terence Howard and Viola Davis as, respectively, Franklin and Nancy Birch) whose child was also abducted come up with a more practical approach: don't get involved, but don't stop Keller--he might actually come up with something (he doesn't get the results he expected, but he does accidentally advance the investigation). By film's end the (more or less) righteous are amply rewarded, the transgressors punished, and even those that have temporarily strayed suffer poetic--and not a little funny--comeuppance.

I don't know. I like how Villeneuve's put together the picture; there are confrontations between Keller and Alex that are ferociously good (though they're careful not to be too explicit), and an ongoing cat-and-mouse game between Keller and investigating officer Detective Loki (Jake Gyllenhaal) that's even better. Villeneuve even pulls off the kind of trick Hitchcock used to do so well, where the audience knows more than the characters onscreen (you want to yell: "HE'S IN THERE! IN THERE, DAMMIT!").

Compare this to David Fincher's Zodiac, however (unfair, but both deal with serial killers, both feature Gyllenhaal in crucial roles) and it's no contest: Fincher offers a puzzle with no definitive solution, no dramatic bringing to justice, no comfortable resolution to the terrible things that happened.

Compare this too to Bong Joon-ho's Memories of Murder, where the torture of captives is actually part of the film's point, actually evokes a specific time in South Korea's political history when enhanced interrogation was standard police procedure, and just as fruitful in producing information (in effect: not very). Difference is Bong Joon-ho's film isn't as morally schematic, and the interrogators display an unsettlingly blase sense of humor about the whole thing; difference is neither Zodiac nor Memories offer consoling fictions to ease us in our contemplation of the unknowable. "Some secrets," they seem to say, "you will never uncover"--Prisoners posit a light at the end of a long and very dark tunnel; Fincher and Bong see no light, no guarantee of an end to the tunnel.

Where everybody knows your name

Two questions come to mind when hearing of Kimberly Peirce's remake of Carrie: obvious and instantaneous ("why bother?"), less obvious and rather wistful ("maybe she can pull it off..."). Now the movie's out we see that the inevitable's happened: the remake has only a fraction of the original's diabolic energy, of its blood-drenched color scheme.

Worse I suppose is that the noble intention--that we look at Stephen King's debut fairy-tale horror novel through a woman's (as opposed to a misogynist's) gaze--doesn't really pan out; this Carrie borrows too much, from the dreamlike slow-motion shower room sequence (discreetly draped with towels this time) to Mrs. White's spectacularly excruciating end (in the novel her heart was stopped). One might mistake this as the original's anemic runt sister, too timid to strike out on its own.

Possibly Peirce's efforts were doomed from the start: Stephen King's novel--his first and as he is the first to admit, rather "lumpy and burned at the bottom"--isn't promising material for a feminist filmmaker. Look at Jack Torrance in The Shining, Andy McGee in Firestarter, Johnny Smith in The Dead Zone, and you can see that King is far more comfortable writing from the male point of view (he had to be prodded to write from Carrie's). Poor Carrie White is abused not just by her classmates, but by her author-creator: the shower scene where the girls toss tampons in the panicked girl's face feels more like a boy's locker room gag than a genuine case of female bullying; the monstrous Mrs. White has the outsized dimensions of a cartoon villain, her Christian denomination left suspiciously vague. De Palma's sensibility--his brand of cruelty--sails in waters and directions not too radically different from King's where Peirce (whose Boys Don't Cry dealt primarily with the confusion found in adolescent women) seems to struggle with a stiff headwind.

All that said, some of Peirce's voice does come through--in that lulu of an opening scene, for starters, where Mrs. White (Julianne Moore, despite her sketchily delineated character managing to deliver the film's most frighteningly effective performance) screams and rolls on bed then pulls her skirt back to discover a bloody lump of a face between her legs. In Carrie and her mother's more fully fleshed-out relationship--Mrs. White dragging her daughter into a tiny closet is bad enough (though I miss the tiny statue of St. Sebastian with its freakish glow-in-the-dark eyes) but more startling is the later scene of reconciliation between mother and daughter, lending the taint of truth to their relationship (even the most abusive bond has its moments of love and tenderness, which is arguably the cruelest hook of all).

Possibly sacrilegious to say this, but beyond the preparatory images (the lights turning red, Sissy Spacek's otherwordly eyes) I never found De Palma's prom-night massacre sequence effective--the split-screens were especially clunky. Peirce adds one interesting idea: her Carrie gestures and waves, shaping the movement of the telekinetically manipulated objects around her with a conductor's flair--literally a symphony of death and destruction.

Sad and not a little disappointing that Peirce wasn't able to break completely free--but this Carrie isn't a bad picture, exactly, just a half-formed one. Like Carrie White herself, it struggles under the shadow of its wilder, more malevolent older relation--but it does have its own virtues, and does bare its own set of fangs.

Hack

Loved Machete; thought it one of the best movies that year, an abominably entertaining fusion of Robert Rodriguez's chaotic talents as filmmaker (he can direct an action sequence well but when shaping a feature-length narrative--well, he can direct an action sequence well) to the white-hot anger felt by Latin-Americans towards immigration hardliners.

To say that Machete Kills strays from that basic formula (Machete; immigration; breasts and bullets) is to understate matters--the sequel is Hell's own Christmas Pageant on fast forward, both confusing and exhausting in equal measure: Machete doesn't only fight on behalf of Latin Americans but for America and the World, and by film's end he's ready to bring the battle to outer space. His anger is largely banked, though; instead we have smoldering embers shooting the occasional spark at specific targets--the proposed US-Mexico border wall, realized as a monumental rampart complete with secret access tunnel for enterprising wetbacks; megawealthy entrepreneurs (Mel Gibson, for once likeably psychotic) who see illegals as a source of cheap feudal labor.

There's a cartoonish exaggeration to this movie that defuses much (but not all) of the sexism, the same time it renders much of the political satire toothless. No, the original wasn't a model of plausibility but for once Rodriguez found a cause truly worth fighting for, and his zeal drove the ungainly mess forward, helped sell it as a committed whatever-it-is. In this sequel the only cause that seems to move Rodriguez forward is the desire to top the first movie; the drive peters out about three-fourths of the way through, about the time when Machete punches his way through the border wall--after that he's like Sean Connery's James Bond at his most parodic, going through the motions for the sake of an overinflated paycheck, or (stranger still) the notion of a feature length (it's a brief one hundred seven minutes and feels like a hundred and fifty). The original Machete was a joke turned into a parody trailer turned into a surprisingly nimble film--part of the pleasure of the picture is watching Rodriguez talk out his ass then actually follow through; too bad Rodriguez fails to pull the stunt a second (and, judging from the dismal boxoffice, a third) time.

And yet--it's still a ballsy move. Trejo is still a chipotle badass. And the movie is still three-fourths a shambolic wonder (can't even say for certain which three, though the intestine-through-the-copter-blades and rust-iron armored car come to mind). Rodriguez is an undisciplined, unpredictable filmmaker, which is his curse and glory. I can't recommend this, but neither can I condemn it; I can only sit there with a goofy guilty grin on my face.

Dead men tell no tales

Paul Greengrass' Captain Phillips I like best for its masterstroke casting: to play Somali pirates, the filmmakers have decided to cast, well, Somalis. Brilliant! Better by far than having, say, Gong Li play a Japanese geisha (who can tell from Asian faces?) or Jennifer Connelly play a Latina housewife (why bother with the character's ethnicity?).

As is, Barkhad Abdi as the pirates' ringleader Muse easily walks away with the picture. Looking half-starved and frighteningly alien (at least he must have looked frighteningly alien to most American audiences), Muse reveals himself to be resourceful, courageous, even rather witty, and Abdi despite the presumed lack of experience (it's his first film role) pulls off each revelation of Muse's character with skill and deceptive simplicity. Probably helps that Greengrass allows Abdi to improve on his role (Abdi came up with a memorable line--"I'm captain here"--during one improvisation).

Hanks--who plays the eponymous captain--faced with such energetically fresh talent had to step up his game; his Captain Phillips is something of a bastard, a hard taskmaster who demands security drills and locked gates at all times; when confronted with pirates, he turns the encounter into a gigantic chess game, always a move ahead of the Somalis, who have to step up their game (the boarding of the ship, done with hooked ladders on rocking skiffs, is a hazardous undertaking comparable to the epic boarding sequence in Richard Lester's classic Juggernaut). I imagine Hanks would make for a wonderful villain, except of course he's the hero here; sadly when he's kidnapped he turns into a rather tiresome hostage victim, throwing hysterical fits in an attempt to maintain the tension (by his third or so fit I wanted to yell at the snipers "shoot him instead!").

Greengrass was told before he undertook this project never to do a film involving water and boats; actually I'd go the opposite way, and recommend that he sticks to boats. When allowed to do hand-to-hand combat, or a chase sequence involving cars or feet his signature shaky-cam (put together chop-suey style with ADHD editing) is well nigh incomprehensible; when stranded out in sea, where you can see the enemy miles off and no one looks very fast going thirty or so knots the suspense slows to an unbearable creep (not necessarily a bad thing, mind), and it's thinking about the situation and anticipating what might happen next (Will they board? Will we hide?) that generates most of the suspense. A coherent Greengrass film? Oh joy!

Footnote: had to happen, and it did. The ship's crew have come out with the claim that some of the events in the film are egregious fiction--that Philips instead of being security conscious was actually reckless, and that instead of offering himself as hostage he was simply taken. Greengrass has responded to the accusations, suggesting this is part of a smear campaign staged by some other Oscar contender (Those useless golden doorstops!). Not sure who to believe (to be honest, I'm tending towards the crew members)--stay tuned for further developments on this tempestuous teacup.

A for Adultery

Understand the admiration for Victor Sjostrom's The Wind: it's a harrowing drama that depicts the character's inner thoughts and perceptions in various imaginative ways, from direct sensation (the howl of the unceasing wind) to sneaking suspicion (a man's greedy eyes stare right through his primly pressed hands) to outright fantasy (endless gusts reveal buried corpse), all the while suggesting the unstoppable nature of a woman's sexuality (the wind doesn't just torment Letty (Lillian Gish in the performance of her career), it is Letty--surrender means giving in to her own sensuality). As an example of the director's art, The Wind is just about unequaled--popularly counted the best of Sjostrom's American films. In comparison Sjostrom's earlier The Scarlet Letter is often considered a lesser work, a tamping down and simplification of Nathaniel Hawthorne's allegorical classic; yet while The Wind fills me with admiration, The Scarlet Letter hits me where I live.

Sjostrom has scriptwriter Francis Marion focus on the love story. Nearly half the film is devoted to Hester Prynne and Reverend Dimmesdale's (Lillian Gish and Swedish actor Lars Hanson) surreptitious foreplay, including a scene where Dimmesdale allows Prynne to drink from a ladle while she's publicly shackled (Bondage and water sports?), another where her underwear hangs out to dry on a shrub for all to see (when Dimmesdale arrives she hides the intimate piece of clothing; when he demands to see what she's hiding she--with the exquisite simplicity of the most artful coquette--surrenders to him the offending apparel). Along with the romance Sjostrom paints an unsparing portrait of the town--the paranoia and hypocrisy, the unsettling fanaticism skewered in a few vignettes (including one where the village gossip is given a taste of her own medicine and mercilessly dunked). Comedy, light and romantic, in a Hawthorne adaptation? But Sjostrom possibly establishes the lighthearted tone to better contrast with the film's darker latter half; the flirtations also play to Gish's strengths as the Eternal Girl-Child, pure of heart yet possessed of a willful, even mischievous, spirit.

This Dimmesdale is a dimmer version of Hawthorne's--gone are the theological and philosophical debates, the psychological nuance of his silent suffering. On paper the man was an introverted intellectual; onscreen Sjostrom has cast a solid Swedish hunk, tall and fair, to match Gish's equally blonde tresses. When he suffers he suffers nobly, giving as good as Gish ever did (and under both Sjostrom and Griffith she gave plenty), helped by Hawthorne's elegantly structured irony: that every word of praise and elevation of status he enjoys is in fact a torment, knowing his true love and her child live in relative squalor.

Gish's Prynne suffers too, though not as subtly. According to Hawthorne's scheme she must be a public martyr enduring not just humiliation and verbal abuse but mud clods hurled at her innocent child (Hawthorne allows her to earn her fellow pilgrims' grudging respect; Sjostrom doesn't--his pilgrims are too dense to recognize heroism when they see it).

Sjostrom backpedals the symbolism, goes heavy on the melodrama: Hawthorne has Prynne simply walk up to public view with her letter ('A'--in bright scarlet--for 'adulterer') already exposed; Sjostrom has Gish unveil her letter in a masochistic strip tease. Later Prynne goes further, unleashing her long blond hair then tearing off the letter and hurling it to the ground; in a perversely reactionary response her daughter insists on pinning it back on her breast.

The whole thing pays off with the film's climax: Dimmesdale walks up to the public scaffold and expires; Prynne cradles him in a Madonna pose. Sjostrom has loaded his picture with only as much weight and symbolism as the medium of silent film can bear (which while intellectually light can be dramatically significant), has arrived at a reduced but still recognizable--still compelling--version of Hawthorne's ending.

And then Sjostrom delivers his stinger. The dim pilgrims, object of Sjostrom's (and Prynne's) scorn, source of Dimmesdale's unthinking fear and guilt, collectively and wordlessly bow their heads. With a gesture they reveal the hypocrisy of their overscrupulous faith; with a gesture they reveal the love and respect they have for the man, a man who in many ways represent them, from his tireless piety and love down to the dirty little secret he kept on his breast (a scarlet "A," which Hawthorne suggests is a kind of stigmata, which Sjostrom turns into an act of self-mutilation). These dense dunderheads unworthy of Prynne and Dimmsedale turn out to be smarter after all (smarter than the reverend, at least): when the best among them is revealed to be yet another adulterating sinner, what else can they do but forgive and accept?

There's that, and then there's the suggestion--again thanks to the pilgrims' gesture--that if Dimmesdale had come clean earlier he might have been able to live a decent, even comfortable, life; that all the torments of hell--all the fire and brimstone and pitchforked demons dancing about you--are nothing, nothing compared to the self-inflicted torments of a guilty heart.

10.22.13

Pray for the best

Denis Villeneuve's Prisoners is a nice example of the airless, minimalist art thriller, set in the rather limited and overfamiliar genre of the child abduction/serial killer flick.

Mind you, there's plenty to like: the generally excellent cast (Paul Dano as mentally challenged Alex Jones and Melissa Leo as his heroically stoic Aunt Holly stand out; Maria Bello is sadly wasted as a cliche of a distressed housewife, confined to bed in a drugged-out stupor); Roger Deakin's bleak cinematography (with Georgia's constant downpour doubling for the wet autumns and sleety winters of Pennsylvania); Villeneuve's understated way of generating suspense quietly, with a minimum of fuss.

I'm less crazy about the script. For all its grimness Prisoners is an ultimately comforting film despite (or perhaps because of) its talk of mazes and mysteries; even someone's statement--that the maze found in a medallion didn't have a solution ("I know, I've tried")--is the kind of declaration of hopelessness you hear just before the dawn. Too many smart guesses solving too many puzzles downgrades one's regard for the film from an eloquent statement on the human condition to an entertainment, nicely made, a couple of steps above NCIS or Law and Order.

Even the moral ambiguity seems neatly parceled out: Hugh Jackman plays Keller Dover, a small business entrepreneur, devout Christian (is he Catholic? It's not made clear), and well-organized survivalist; when his daughter is taken the law requires that he sit still and wait while the police do their job but his can-do, by-the-bootstraps ethos ("Pray for the best, prepare for the worst") demands that he do something--so he does. The resulting scenario is the kind of cobbled-together 'what-if' situation favored by pro-torture advocates (what if your child was in danger?). The next-door neighbors (Terence Howard and Viola Davis as, respectively, Franklin and Nancy Birch) whose child was also abducted come up with a more practical approach: don't get involved, but don't stop Keller--he might actually come up with something (he doesn't get the results he expected, but he does accidentally advance the investigation). By film's end the (more or less) righteous are amply rewarded, the transgressors punished, and even those that have temporarily strayed suffer poetic--and not a little funny--comeuppance.

I don't know. I like how Villeneuve's put together the picture; there are confrontations between Keller and Alex that are ferociously good (though they're careful not to be too explicit), and an ongoing cat-and-mouse game between Keller and investigating officer Detective Loki (Jake Gyllenhaal) that's even better. Villeneuve even pulls off the kind of trick Hitchcock used to do so well, where the audience knows more than the characters onscreen (you want to yell: "HE'S IN THERE! IN THERE, DAMMIT!").

Compare this to David Fincher's Zodiac, however (unfair, but both deal with serial killers, both feature Gyllenhaal in crucial roles) and it's no contest: Fincher offers a puzzle with no definitive solution, no dramatic bringing to justice, no comfortable resolution to the terrible things that happened.

Compare this too to Bong Joon-ho's Memories of Murder, where the torture of captives is actually part of the film's point, actually evokes a specific time in South Korea's political history when enhanced interrogation was standard police procedure, and just as fruitful in producing information (in effect: not very). Difference is Bong Joon-ho's film isn't as morally schematic, and the interrogators display an unsettlingly blase sense of humor about the whole thing; difference is neither Zodiac nor Memories offer consoling fictions to ease us in our contemplation of the unknowable. "Some secrets," they seem to say, "you will never uncover"--Prisoners posit a light at the end of a long and very dark tunnel; Fincher and Bong see no light, no guarantee of an end to the tunnel.

Where everybody knows your name

Two questions come to mind when hearing of Kimberly Peirce's remake of Carrie: obvious and instantaneous ("why bother?"), less obvious and rather wistful ("maybe she can pull it off..."). Now the movie's out we see that the inevitable's happened: the remake has only a fraction of the original's diabolic energy, of its blood-drenched color scheme.

Worse I suppose is that the noble intention--that we look at Stephen King's debut fairy-tale horror novel through a woman's (as opposed to a misogynist's) gaze--doesn't really pan out; this Carrie borrows too much, from the dreamlike slow-motion shower room sequence (discreetly draped with towels this time) to Mrs. White's spectacularly excruciating end (in the novel her heart was stopped). One might mistake this as the original's anemic runt sister, too timid to strike out on its own.

Possibly Peirce's efforts were doomed from the start: Stephen King's novel--his first and as he is the first to admit, rather "lumpy and burned at the bottom"--isn't promising material for a feminist filmmaker. Look at Jack Torrance in The Shining, Andy McGee in Firestarter, Johnny Smith in The Dead Zone, and you can see that King is far more comfortable writing from the male point of view (he had to be prodded to write from Carrie's). Poor Carrie White is abused not just by her classmates, but by her author-creator: the shower scene where the girls toss tampons in the panicked girl's face feels more like a boy's locker room gag than a genuine case of female bullying; the monstrous Mrs. White has the outsized dimensions of a cartoon villain, her Christian denomination left suspiciously vague. De Palma's sensibility--his brand of cruelty--sails in waters and directions not too radically different from King's where Peirce (whose Boys Don't Cry dealt primarily with the confusion found in adolescent women) seems to struggle with a stiff headwind.

All that said, some of Peirce's voice does come through--in that lulu of an opening scene, for starters, where Mrs. White (Julianne Moore, despite her sketchily delineated character managing to deliver the film's most frighteningly effective performance) screams and rolls on bed then pulls her skirt back to discover a bloody lump of a face between her legs. In Carrie and her mother's more fully fleshed-out relationship--Mrs. White dragging her daughter into a tiny closet is bad enough (though I miss the tiny statue of St. Sebastian with its freakish glow-in-the-dark eyes) but more startling is the later scene of reconciliation between mother and daughter, lending the taint of truth to their relationship (even the most abusive bond has its moments of love and tenderness, which is arguably the cruelest hook of all).

Possibly sacrilegious to say this, but beyond the preparatory images (the lights turning red, Sissy Spacek's otherwordly eyes) I never found De Palma's prom-night massacre sequence effective--the split-screens were especially clunky. Peirce adds one interesting idea: her Carrie gestures and waves, shaping the movement of the telekinetically manipulated objects around her with a conductor's flair--literally a symphony of death and destruction.

Sad and not a little disappointing that Peirce wasn't able to break completely free--but this Carrie isn't a bad picture, exactly, just a half-formed one. Like Carrie White herself, it struggles under the shadow of its wilder, more malevolent older relation--but it does have its own virtues, and does bare its own set of fangs.

Hack

Loved Machete; thought it one of the best movies that year, an abominably entertaining fusion of Robert Rodriguez's chaotic talents as filmmaker (he can direct an action sequence well but when shaping a feature-length narrative--well, he can direct an action sequence well) to the white-hot anger felt by Latin-Americans towards immigration hardliners.

To say that Machete Kills strays from that basic formula (Machete; immigration; breasts and bullets) is to understate matters--the sequel is Hell's own Christmas Pageant on fast forward, both confusing and exhausting in equal measure: Machete doesn't only fight on behalf of Latin Americans but for America and the World, and by film's end he's ready to bring the battle to outer space. His anger is largely banked, though; instead we have smoldering embers shooting the occasional spark at specific targets--the proposed US-Mexico border wall, realized as a monumental rampart complete with secret access tunnel for enterprising wetbacks; megawealthy entrepreneurs (Mel Gibson, for once likeably psychotic) who see illegals as a source of cheap feudal labor.

There's a cartoonish exaggeration to this movie that defuses much (but not all) of the sexism, the same time it renders much of the political satire toothless. No, the original wasn't a model of plausibility but for once Rodriguez found a cause truly worth fighting for, and his zeal drove the ungainly mess forward, helped sell it as a committed whatever-it-is. In this sequel the only cause that seems to move Rodriguez forward is the desire to top the first movie; the drive peters out about three-fourths of the way through, about the time when Machete punches his way through the border wall--after that he's like Sean Connery's James Bond at his most parodic, going through the motions for the sake of an overinflated paycheck, or (stranger still) the notion of a feature length (it's a brief one hundred seven minutes and feels like a hundred and fifty). The original Machete was a joke turned into a parody trailer turned into a surprisingly nimble film--part of the pleasure of the picture is watching Rodriguez talk out his ass then actually follow through; too bad Rodriguez fails to pull the stunt a second (and, judging from the dismal boxoffice, a third) time.

And yet--it's still a ballsy move. Trejo is still a chipotle badass. And the movie is still three-fourths a shambolic wonder (can't even say for certain which three, though the intestine-through-the-copter-blades and rust-iron armored car come to mind). Rodriguez is an undisciplined, unpredictable filmmaker, which is his curse and glory. I can't recommend this, but neither can I condemn it; I can only sit there with a goofy guilty grin on my face.

Dead men tell no tales

Paul Greengrass' Captain Phillips I like best for its masterstroke casting: to play Somali pirates, the filmmakers have decided to cast, well, Somalis. Brilliant! Better by far than having, say, Gong Li play a Japanese geisha (who can tell from Asian faces?) or Jennifer Connelly play a Latina housewife (why bother with the character's ethnicity?).

As is, Barkhad Abdi as the pirates' ringleader Muse easily walks away with the picture. Looking half-starved and frighteningly alien (at least he must have looked frighteningly alien to most American audiences), Muse reveals himself to be resourceful, courageous, even rather witty, and Abdi despite the presumed lack of experience (it's his first film role) pulls off each revelation of Muse's character with skill and deceptive simplicity. Probably helps that Greengrass allows Abdi to improve on his role (Abdi came up with a memorable line--"I'm captain here"--during one improvisation).

Hanks--who plays the eponymous captain--faced with such energetically fresh talent had to step up his game; his Captain Phillips is something of a bastard, a hard taskmaster who demands security drills and locked gates at all times; when confronted with pirates, he turns the encounter into a gigantic chess game, always a move ahead of the Somalis, who have to step up their game (the boarding of the ship, done with hooked ladders on rocking skiffs, is a hazardous undertaking comparable to the epic boarding sequence in Richard Lester's classic Juggernaut). I imagine Hanks would make for a wonderful villain, except of course he's the hero here; sadly when he's kidnapped he turns into a rather tiresome hostage victim, throwing hysterical fits in an attempt to maintain the tension (by his third or so fit I wanted to yell at the snipers "shoot him instead!").

Greengrass was told before he undertook this project never to do a film involving water and boats; actually I'd go the opposite way, and recommend that he sticks to boats. When allowed to do hand-to-hand combat, or a chase sequence involving cars or feet his signature shaky-cam (put together chop-suey style with ADHD editing) is well nigh incomprehensible; when stranded out in sea, where you can see the enemy miles off and no one looks very fast going thirty or so knots the suspense slows to an unbearable creep (not necessarily a bad thing, mind), and it's thinking about the situation and anticipating what might happen next (Will they board? Will we hide?) that generates most of the suspense. A coherent Greengrass film? Oh joy!

Footnote: had to happen, and it did. The ship's crew have come out with the claim that some of the events in the film are egregious fiction--that Philips instead of being security conscious was actually reckless, and that instead of offering himself as hostage he was simply taken. Greengrass has responded to the accusations, suggesting this is part of a smear campaign staged by some other Oscar contender (Those useless golden doorstops!). Not sure who to believe (to be honest, I'm tending towards the crew members)--stay tuned for further developments on this tempestuous teacup.

A for Adultery

Understand the admiration for Victor Sjostrom's The Wind: it's a harrowing drama that depicts the character's inner thoughts and perceptions in various imaginative ways, from direct sensation (the howl of the unceasing wind) to sneaking suspicion (a man's greedy eyes stare right through his primly pressed hands) to outright fantasy (endless gusts reveal buried corpse), all the while suggesting the unstoppable nature of a woman's sexuality (the wind doesn't just torment Letty (Lillian Gish in the performance of her career), it is Letty--surrender means giving in to her own sensuality). As an example of the director's art, The Wind is just about unequaled--popularly counted the best of Sjostrom's American films. In comparison Sjostrom's earlier The Scarlet Letter is often considered a lesser work, a tamping down and simplification of Nathaniel Hawthorne's allegorical classic; yet while The Wind fills me with admiration, The Scarlet Letter hits me where I live.

Sjostrom has scriptwriter Francis Marion focus on the love story. Nearly half the film is devoted to Hester Prynne and Reverend Dimmesdale's (Lillian Gish and Swedish actor Lars Hanson) surreptitious foreplay, including a scene where Dimmesdale allows Prynne to drink from a ladle while she's publicly shackled (Bondage and water sports?), another where her underwear hangs out to dry on a shrub for all to see (when Dimmesdale arrives she hides the intimate piece of clothing; when he demands to see what she's hiding she--with the exquisite simplicity of the most artful coquette--surrenders to him the offending apparel). Along with the romance Sjostrom paints an unsparing portrait of the town--the paranoia and hypocrisy, the unsettling fanaticism skewered in a few vignettes (including one where the village gossip is given a taste of her own medicine and mercilessly dunked). Comedy, light and romantic, in a Hawthorne adaptation? But Sjostrom possibly establishes the lighthearted tone to better contrast with the film's darker latter half; the flirtations also play to Gish's strengths as the Eternal Girl-Child, pure of heart yet possessed of a willful, even mischievous, spirit.

This Dimmesdale is a dimmer version of Hawthorne's--gone are the theological and philosophical debates, the psychological nuance of his silent suffering. On paper the man was an introverted intellectual; onscreen Sjostrom has cast a solid Swedish hunk, tall and fair, to match Gish's equally blonde tresses. When he suffers he suffers nobly, giving as good as Gish ever did (and under both Sjostrom and Griffith she gave plenty), helped by Hawthorne's elegantly structured irony: that every word of praise and elevation of status he enjoys is in fact a torment, knowing his true love and her child live in relative squalor.

Gish's Prynne suffers too, though not as subtly. According to Hawthorne's scheme she must be a public martyr enduring not just humiliation and verbal abuse but mud clods hurled at her innocent child (Hawthorne allows her to earn her fellow pilgrims' grudging respect; Sjostrom doesn't--his pilgrims are too dense to recognize heroism when they see it).

Sjostrom backpedals the symbolism, goes heavy on the melodrama: Hawthorne has Prynne simply walk up to public view with her letter ('A'--in bright scarlet--for 'adulterer') already exposed; Sjostrom has Gish unveil her letter in a masochistic strip tease. Later Prynne goes further, unleashing her long blond hair then tearing off the letter and hurling it to the ground; in a perversely reactionary response her daughter insists on pinning it back on her breast.

The whole thing pays off with the film's climax: Dimmesdale walks up to the public scaffold and expires; Prynne cradles him in a Madonna pose. Sjostrom has loaded his picture with only as much weight and symbolism as the medium of silent film can bear (which while intellectually light can be dramatically significant), has arrived at a reduced but still recognizable--still compelling--version of Hawthorne's ending.

And then Sjostrom delivers his stinger. The dim pilgrims, object of Sjostrom's (and Prynne's) scorn, source of Dimmesdale's unthinking fear and guilt, collectively and wordlessly bow their heads. With a gesture they reveal the hypocrisy of their overscrupulous faith; with a gesture they reveal the love and respect they have for the man, a man who in many ways represent them, from his tireless piety and love down to the dirty little secret he kept on his breast (a scarlet "A," which Hawthorne suggests is a kind of stigmata, which Sjostrom turns into an act of self-mutilation). These dense dunderheads unworthy of Prynne and Dimmsedale turn out to be smarter after all (smarter than the reverend, at least): when the best among them is revealed to be yet another adulterating sinner, what else can they do but forgive and accept?

There's that, and then there's the suggestion--again thanks to the pilgrims' gesture--that if Dimmesdale had come clean earlier he might have been able to live a decent, even comfortable, life; that all the torments of hell--all the fire and brimstone and pitchforked demons dancing about you--are nothing, nothing compared to the self-inflicted torments of a guilty heart.

10.22.13

Wednesday, October 09, 2013

Wings of Honneamise (Hiroyuki Yamaga, 1987)

James Cameron on Gravity: "it’s the best space film ever done"

Mr. Cameron's entitled to his opinion of course, but considering that lately he's taken to mistaking the size of his movie budgets for the size of his penis, can't hold his opinion in high regard.

I do offer an alternative--something I once wrote, scared up in hasty response:

Not impossible, spending an entire animated feature on a space mission; matter of fact it's been done before, with Hiroyuki Yamaga's magnificent Wings of Honneamise, about a fictional country on a parallel Earth struggling to send a man into space.

The level of thought, the density of detail and inventiveness of design the filmmakers (character designer Yoshiyuki Sadamoto and effects artist Hideaki Anno would later work on an even more ambitious project; actor-composer Ryuichi Sakamoto provided the thoughtful film score) pour into the film is staggering: the nozzle assembly of the Brobdingnagian engine resembles that of a Soviet Soyuz (Russian for 'rocket') engine; the country's entire society is fully realized, from the doughnut-shaped coins they drop into ticketing machines and triangular spoons used to eat thick stews to the faintly risible feathery caps worn by the space cadets, giving them a faint resemblance to blue flamingos.

The film's tone isn't one of relentless scientific optimism. The space force doesn't enjoy a high reputation; if anything, people regard it as something of a joke. The cadets and scientists have to earn the right to be proud of themselves, work hard to solve all technological problems, undergo rigorous training, stay above the local and international political intrigues that threaten to overwhelm the program.

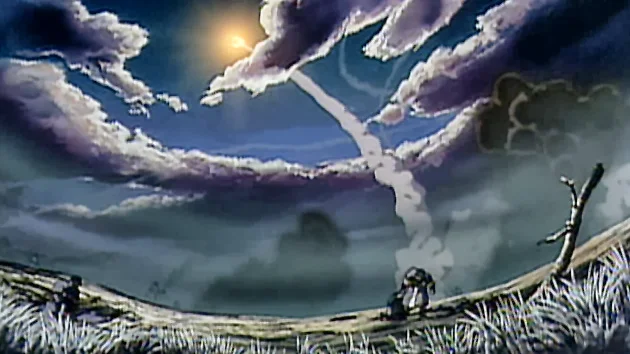

By film's end said intrigues do take over--war breaks out on the border, and we're treated to the sight of gigantic armored engines and fleets of fighter planes mobilizing into action. Missiles are launched, artillery shells fired, and while high calibre ordnance trace their deadly trajectory through the brilliant blue sky, the scientists (who in any lesser picture would have canceled the program 'in the interest of safety' (pfui!) decide to push through and launch the sucker anyway.

The launch is impressive, a symphony of clashing metal and surging fire; the thousand-ton technological tower shudders and takes to the heavens in an agonizingly slow climb, accelerating into a streak of smoke and flame. The space traveler (the uchunaut?) peers out his tiny window and sees--well, sees the Earth: a vast swirl of cloud and water (and occasional bar of land) down below, bizarrely still (considering the battleground he left behind just minutes before), impossibly beautiful. And he has what the very best science fiction (as opposed to slam-bang thank you ma'am sci-fi) is able to deliver, thanks to a simple change of perspective (in this case some hundred miles straight up): an epiphany. We are just ants in an immense world, he realizes; whatever we do is insignificant, whatever hates and lusts we inflict on each other unimportant. We do not truly matter, and the sooner we realize that, the better off we will be...

A far cry from Gravity's unmistakeable (if understated) one-woman triumphalism, which for all the size of its budget and elaborate effects, seems oddly unambitious. "The only true wisdom is in knowing you know nothing" Socrates once said; in which case, watching Honneammise, where a prodigious amount of work and money and talent expended leads us to this humbling conclusion, would make for a good first step.

10.9.13

Tuesday, October 08, 2013

Notorious (Alfred Hitchcock, 1946)

(An old post reposted, just because)

Saw this for the umpteenth time and for the umpteenth time was blown away. Poor Alicia (Bergman), with her nymphomanic appetites--which, it's suggested, stem from a deep inner conflict with her father; poor Devlin (Grant), who shies away from women because of painful experiences in the past with women like Alicia; poor Alex (Rains), the, strange to say, most innocent of the three (strange because he's the villain), insecure because she's so beautiful and he's so old. Three unhappy people talking at cross purposes with each other, lying to each other, yearning that the other open up to him or her. It's about as painfully funny a portrait of an unhappy love triangle as any I can think of, and that there's an espionage plot seamlessly grafted on to the affair giving it a breathless urgency makes the film all the more remarkable.

Everyone points to the famous scene early in the picture where Hitchcock circumvents the Production Code about the permissible length of kisses (about three seconds) by having Alicia and Devlin pleasure each other with a series of shorter kisses, all the while locked in a casual yet carnal embrace, giving what is unmistakeably meant to be foreplay (it could as easily be postcoital but Hitchcock possibly to placate the censors pointedly shows them arriving at the apartment beforehand)--a brief buss, a nuzzle, an earlobe caressed, a nibble, the languorous sound of the waves cascading leisurely down the beach. Lovely scene, but really a prelude to the hot sizzle Hitchcock delivers later at Alex's house party, where in the official story Devlin has to think up a quick excuse for him and Alicia to be near the fateful basement (storehouse of the film's official MacGuffin: powdered uranium in wine bottles) and grabs Alicia, giving her a hard kiss. The allure of forbidden fruit (she's married to Alex), the added spice of exhibitionism (she's revealing her infidelity to her husband) flavors the thousand-watt charge of her frustrated feelings for Devlin unexpectedly given chance to vent: she gets into it (the way only Bergman with her astonishing intimacy with the camera can), she abandons herself to the moment, her whispers to Devlin are hoarse with lust and hopeless love.

And while Devlin and Alicia's romance/hatred for each other dominates the audience's attention, you can't help but point out another just-as-crucial couple onscreen, tearing each others hearts out: Alex and his mother Madame Sebastian (Leopoldine), who Alex loves and hates in equal measure and who loves and suffocates him in turn, heartbroken when her son chooses Alicia over her, to the point that she takes to bed (presumably to die). Then the magnificent moment when Alex comes to her bedroom, and admits failure (of his marriage, of his manhood); and Madame Anna--rising from her bed, putting a penis (sorry, cigarette) in her mouth--nonchalantly lighting it (symbolizing, in effect, the rekindling of her virility).

Then the ending, the slow glide down the stairways, the dread and terror one feels for Alicia that so neatly turns about with the simple slamming of a car door and settles unshakeably on Alex's shoulders. Alicia's glowing expression as she looks at the man she truly loves, while the man who truly loves her (and he does; he only turns malignant when he learns of her betrayal, of the danger she has put him in--whereas Devlin's regard for Alicia is never similarly tested) is left behind to face his destiny. Hitchcock has passed judgment and we're stunned, unsure at the justice of the verdict--but that could be part of Hitchcock's point: that in the genre of romantic thrillers (and life itself if you want to go in that direction) conclusions are rarely fair, happy endings not always deserving, beauty is its own (if unwarranted, even unwanted) reward. C'est la mort.

8.29.04

Monday, October 07, 2013

Gravity (Alfonso Cuaron)

What goes up

(WARNING: film's plot, narrative twists and ending discussed in close and explicit detail)

Alfonso Cuaron's Gravity comes with its own planet-sized hype: about the 17-minute opening shot, about the vertiginous sense of depth (enhanced by the 3D process), about the unprecedented scientific veracity.

The basic premise turns on a frightening demonstration of the Kessler Syndrome: the Russians have blown up a satellite and the resulting debris have pingponged their way across space towards the orbiting space shuttle in a rain of high-velocity scrap (it's a serious real-life problem and collisions between satellites have been recorded). Doctor Ryan Stone (Sandra Bullock) and Astronaut Matt Kowalski (George Clooney) are the only survivors and must make their way back to Earth using crippled equipment under adverse circumstances.

More interesting than the premise--or the actors, really--is Cuaron's attempt at telling the story in as dramatic and realistic a manner as possible. Much of the action happens in real time, in lengthy tracking shots; danger when it approaches is spotted quickly--what gives danger in space its unique quality is that you often can't do much about it even if you do see it, or know it's coming (the satellite debris that wreaks havoc on the shuttle will take ninety minutes to circle the globe and menace the shuttle again). Collisions are spectacular but--unsettlingly--occur in silence (well, not total silence; to Cuaron's credit he gives us muffled thuds, presumably conducted through umbilical lines, or through thick work gloves with a tenuous grip on an exterior rung).

For those interested Cuaron doesn't achieve complete realism: Stone would have done better to have the robot arm or Shuttle Remote Maneuvering System (SRMS) lower her (or she could have simply climbed down the arm's length) than to wait for Kowalski to rescue her with the infinitely slower Manned Maneuvering Unit (MMU); the International Space Station and Hubble Telescope (and for that matter most communication satellites) are on widely differing orbits, the distances (not to mention velocities involved) impossible to cross using just the MMU; Stone initiates re-entry with a minimum of attitude adjustment (as in none), even if re-entry is actually a trickier and more dangerous process than what you see onscreen. Cuaron himself admits he sacrificed some accuracy for story purposes.

That isn't all Cuaron sacrifices: I'm guessing in its earlier incarnation the film was devoid of music, and Cuaron after a few less-than-positive test screenings was pressured to add a score--more an orchestrated hum, actually--to enhance drama and tension. Big mistake, I'd say; Stanley Kubrick in 2001 (still my idea of most accurate onscreen depiction of space) suggested the depths of space not just through miniatures posed against yards of black felt but through Kubrick's freakishly disciplined mis-en-scene and totalitarian control of details (including a leisurely editing rhythm and overall pace that evokes the sense of vast reaches being crossed): when Frank Poole is lost in space it takes David Bowman long minutes to rescue him--no music to shatter the expectant mood, no cheap hysterics to suggest desperation (at most Bowman's speech grows more clipped and annoyed). Cuaron cheats; there may not be any ambient sound in his version of space but the rather loud and mechanical score guarantees that there also won't be a lot of boredom experienced, especially by the ADHD crowd (a probably significant demographic).

Richard Brody in the New Yorker points out a more serious flaw: the film has no inner life, not much apparent art mediating what the characters see and what the camera sees (actually between what has been digitally composed for the characters to see and what has been digitally composed for the camera to see); what point of view there is is revealed to be blandly heroic and competent. Good point (even if Brody erroneously (least I assume it's erroneous; he's always welcome to explain himself) suggests that Jupiter's massive gravity and not Kubrick's mysterious monolith triggered the mind-bending space trip in 2001), though you wonder at his attempt to connect the film to documentaries.

Yes, the film is a shallow concept; it isn't meant to be anything more than shallow, and is hardly the first film to be so. Films about survival are a somewhat varied genre (recent examples off the top of my head: Danny Boyle's hyperbolic--and not in a good way--127 Hours; Kris Kentis' efficient Open Water; Robert Zemeckis' idiosyncratically humorous Cast Away) but Cuaron's picture has less in common with them (for one thing the protagonist--and why haven't more people thought of this?--is female) or with documentaries than with the kind of gimmicky projects filmmakers concocted to challenge themselves: Hitchcock's Lifeboat (movie set entirely in a lifeboat), Rope (movie apparently composed of a single unbroken shot), and (most effectively) Rear Window (movie set entirely in an apartment); Gus Van Sant's shot-by-shot remake of Psycho (I suppose I'm stretching now), which someone once described to me as "the ultimate film-school exercise."

I'd also call this film cousin (at least in spirit) to Howard Hawks' The Thing, where efficiency and smarts are the rule, the monster is merely a problem to be solved, and the only hint of inner life on display is the sexual challenge presented to bland Captain Hendrey by the surprisingly sexy (this is Antarctica after all, where after months in that frozen landscape even a husky would look appealing) Nikki Nicholson. Hendrey and his men hunt the creature with the methodical cool of professionals, the way Clooney's Kowalski proposes solutions to problems like a professional chess player--in space the biggest issue aren't events that inspire fear and anxiety, but clearing one's head of fear and anxiety: "focus," you could hear Kowalski lecturing Stone in so many words, "is all." Stone's one act of imagination is important solely for the coolly logical solution handed to her, a gift from beyond the grave; otherwise Cuaron could have snipped it from the picture.

But then, Hawks might have cut the scene too. When Hendrey opens a door and finds The Thing standing there snarling he doesn't suddenly pause to debate the random nature of the universe, the poignant fragility of life and one's uncertain role in the flow of things; he shuts the door. Intellectual asides, Hendry must have thought, are literally beside the point here.

(Talking about asides--Gravity's finale, involving the fiery re-entry of thousands of shards of metal into Earth's atmosphere, features some of the most unpersuasive digitally-composed flames I've seen recently (not a high bar, there). To see a re-entry done properly try watching Philip Kaufman's The Right Stuff--where, like Kubrick, Kaufman relies on old-fashioned on-camera tricks and pyrotechnics to achieve his effects)

Hitchcock (and Hawks to a lesser extent) did have kinky stuff going on: in Lifeboat the smartest, sneakiest, most-likely-to-survive member on board is the innocent-looking Nazi; Rope's killers are motivated by Nietzschean concepts; Rear Window questions the morality of peeping, even if it does involve uncovering a possible murder. It's possible to argue that these elements are Hitchcock's true motives for making the films, that he had something weighty and worthwhile to tell the world; it's also possible to argue these are what he'd call MacGuffins, unimportant devices designed solely to get the plot going (remember that Hitchcock regretted the killing of a crucial character in Sabotage--but only because (or so he says) it repelled the audience with its wanton cruelty). Part of Hitchcock's appeal, I suspect--part of why he's such a fascinating conundrum that resists unraveling--comes from never really clarifying his own attitude on the subject.

No, Cuaron's film doesn't offer much beyond what's there on the (admittedly well-made and exciting) surface (a subplot involving Dr. Stone and her daughter practically reeks of MacGuffinism), but I submit that sometimes surface is enough--that the visual challenge Cuaron set for himself is interesting enough. And if that affirmation doesn't satisfy you, ask Cuaron or (before him) Hitchcock, only don't expect a straight answer.

10.7.13

(WARNING: film's plot, narrative twists and ending discussed in close and explicit detail)

Alfonso Cuaron's Gravity comes with its own planet-sized hype: about the 17-minute opening shot, about the vertiginous sense of depth (enhanced by the 3D process), about the unprecedented scientific veracity.

The basic premise turns on a frightening demonstration of the Kessler Syndrome: the Russians have blown up a satellite and the resulting debris have pingponged their way across space towards the orbiting space shuttle in a rain of high-velocity scrap (it's a serious real-life problem and collisions between satellites have been recorded). Doctor Ryan Stone (Sandra Bullock) and Astronaut Matt Kowalski (George Clooney) are the only survivors and must make their way back to Earth using crippled equipment under adverse circumstances.

More interesting than the premise--or the actors, really--is Cuaron's attempt at telling the story in as dramatic and realistic a manner as possible. Much of the action happens in real time, in lengthy tracking shots; danger when it approaches is spotted quickly--what gives danger in space its unique quality is that you often can't do much about it even if you do see it, or know it's coming (the satellite debris that wreaks havoc on the shuttle will take ninety minutes to circle the globe and menace the shuttle again). Collisions are spectacular but--unsettlingly--occur in silence (well, not total silence; to Cuaron's credit he gives us muffled thuds, presumably conducted through umbilical lines, or through thick work gloves with a tenuous grip on an exterior rung).

For those interested Cuaron doesn't achieve complete realism: Stone would have done better to have the robot arm or Shuttle Remote Maneuvering System (SRMS) lower her (or she could have simply climbed down the arm's length) than to wait for Kowalski to rescue her with the infinitely slower Manned Maneuvering Unit (MMU); the International Space Station and Hubble Telescope (and for that matter most communication satellites) are on widely differing orbits, the distances (not to mention velocities involved) impossible to cross using just the MMU; Stone initiates re-entry with a minimum of attitude adjustment (as in none), even if re-entry is actually a trickier and more dangerous process than what you see onscreen. Cuaron himself admits he sacrificed some accuracy for story purposes.

That isn't all Cuaron sacrifices: I'm guessing in its earlier incarnation the film was devoid of music, and Cuaron after a few less-than-positive test screenings was pressured to add a score--more an orchestrated hum, actually--to enhance drama and tension. Big mistake, I'd say; Stanley Kubrick in 2001 (still my idea of most accurate onscreen depiction of space) suggested the depths of space not just through miniatures posed against yards of black felt but through Kubrick's freakishly disciplined mis-en-scene and totalitarian control of details (including a leisurely editing rhythm and overall pace that evokes the sense of vast reaches being crossed): when Frank Poole is lost in space it takes David Bowman long minutes to rescue him--no music to shatter the expectant mood, no cheap hysterics to suggest desperation (at most Bowman's speech grows more clipped and annoyed). Cuaron cheats; there may not be any ambient sound in his version of space but the rather loud and mechanical score guarantees that there also won't be a lot of boredom experienced, especially by the ADHD crowd (a probably significant demographic).

Richard Brody in the New Yorker points out a more serious flaw: the film has no inner life, not much apparent art mediating what the characters see and what the camera sees (actually between what has been digitally composed for the characters to see and what has been digitally composed for the camera to see); what point of view there is is revealed to be blandly heroic and competent. Good point (even if Brody erroneously (least I assume it's erroneous; he's always welcome to explain himself) suggests that Jupiter's massive gravity and not Kubrick's mysterious monolith triggered the mind-bending space trip in 2001), though you wonder at his attempt to connect the film to documentaries.

Yes, the film is a shallow concept; it isn't meant to be anything more than shallow, and is hardly the first film to be so. Films about survival are a somewhat varied genre (recent examples off the top of my head: Danny Boyle's hyperbolic--and not in a good way--127 Hours; Kris Kentis' efficient Open Water; Robert Zemeckis' idiosyncratically humorous Cast Away) but Cuaron's picture has less in common with them (for one thing the protagonist--and why haven't more people thought of this?--is female) or with documentaries than with the kind of gimmicky projects filmmakers concocted to challenge themselves: Hitchcock's Lifeboat (movie set entirely in a lifeboat), Rope (movie apparently composed of a single unbroken shot), and (most effectively) Rear Window (movie set entirely in an apartment); Gus Van Sant's shot-by-shot remake of Psycho (I suppose I'm stretching now), which someone once described to me as "the ultimate film-school exercise."

I'd also call this film cousin (at least in spirit) to Howard Hawks' The Thing, where efficiency and smarts are the rule, the monster is merely a problem to be solved, and the only hint of inner life on display is the sexual challenge presented to bland Captain Hendrey by the surprisingly sexy (this is Antarctica after all, where after months in that frozen landscape even a husky would look appealing) Nikki Nicholson. Hendrey and his men hunt the creature with the methodical cool of professionals, the way Clooney's Kowalski proposes solutions to problems like a professional chess player--in space the biggest issue aren't events that inspire fear and anxiety, but clearing one's head of fear and anxiety: "focus," you could hear Kowalski lecturing Stone in so many words, "is all." Stone's one act of imagination is important solely for the coolly logical solution handed to her, a gift from beyond the grave; otherwise Cuaron could have snipped it from the picture.

But then, Hawks might have cut the scene too. When Hendrey opens a door and finds The Thing standing there snarling he doesn't suddenly pause to debate the random nature of the universe, the poignant fragility of life and one's uncertain role in the flow of things; he shuts the door. Intellectual asides, Hendry must have thought, are literally beside the point here.

(Talking about asides--Gravity's finale, involving the fiery re-entry of thousands of shards of metal into Earth's atmosphere, features some of the most unpersuasive digitally-composed flames I've seen recently (not a high bar, there). To see a re-entry done properly try watching Philip Kaufman's The Right Stuff--where, like Kubrick, Kaufman relies on old-fashioned on-camera tricks and pyrotechnics to achieve his effects)

Hitchcock (and Hawks to a lesser extent) did have kinky stuff going on: in Lifeboat the smartest, sneakiest, most-likely-to-survive member on board is the innocent-looking Nazi; Rope's killers are motivated by Nietzschean concepts; Rear Window questions the morality of peeping, even if it does involve uncovering a possible murder. It's possible to argue that these elements are Hitchcock's true motives for making the films, that he had something weighty and worthwhile to tell the world; it's also possible to argue these are what he'd call MacGuffins, unimportant devices designed solely to get the plot going (remember that Hitchcock regretted the killing of a crucial character in Sabotage--but only because (or so he says) it repelled the audience with its wanton cruelty). Part of Hitchcock's appeal, I suspect--part of why he's such a fascinating conundrum that resists unraveling--comes from never really clarifying his own attitude on the subject.

No, Cuaron's film doesn't offer much beyond what's there on the (admittedly well-made and exciting) surface (a subplot involving Dr. Stone and her daughter practically reeks of MacGuffinism), but I submit that sometimes surface is enough--that the visual challenge Cuaron set for himself is interesting enough. And if that affirmation doesn't satisfy you, ask Cuaron or (before him) Hitchcock, only don't expect a straight answer.

10.7.13

Sunday, October 06, 2013

Sanda Wong (Gerardo de Leon, 1955)

And the yearlong celebration of Gerardo de Leon's centennial continues with an Oct. 12 at 4 pm screening of this film, at the CCP Dream Theater

Resurrection of a Lost Philippine Classic

Gerry De Leon's Sanda Wong, made in 1955, has been lost for years; only through the efforts of film historian-archivist-distributor Teddy Co, has a print been located in Hongkong, brought home to this country, and with the help of Mowelfund and SOFIA (Society of Film Archivists), restored.

Sanda Wong was a coproduction between Philippine and Hongkong filmmaking outfits (and where are the international co-productions to be found today?)--a strictly commercial venture, out to make a profit. It was conceived as shallow entertainment, and on its own purely mercenary terms, it's a success. This isn't a literary production like Manuel Silos' great Biyaya Ng Lupa (Blessings of the Land, 1959); it isn't even considered to be among Gerry De Leon's best works.

What Sanda Wong is, though--what's so surprising about it--is one of the most sheerly enjoyable Filipino films ever made. I mean--bandits and magic rings! Secret dens, hidden treasures, pythons that pop out of nowhere. This is in the great tradition of Gunga Din, The Thief Of Baghdad, The Adventures Of Robin Hood: gloriously irrelevant confections, filled with contrivances just a step sideways from real life, slightly larger than real life, and as entertaining as hell. I actually enjoyed Sanda Wong more than Thief Of Baghdad--heresy to the ears of a traditional film critic, until you realize that the director, Michael Powell, was hamstrung by a huge, problem-ridden production (input from other directors brought in to fix the problems probably didn't help). Powell's filmmaking in Thief was square in a big-budgeted, Important Picture way; De Leon was working with a larger than usual budget here, but by Hollywood standards it's miniscule--he still had to improvise, and his filmmaking is lean and hungry and evocatively imaginative.

But you don't have to be some kind of film expert to appreciate Sanda Wong; you don't have to exclaim "John Ford!" every time you see a figure framed dramatically against a brilliant white sky, or "De Sade!" every time Wong (Jose Padilla, Jr.) raised a whip against his beautiful Amazon beauty (Lilia Dizon, mother of modern-day leading man Christopher De Leon). Sanda Wong is gripping drama in its own right, a Jacobean struggle between rich landowner Liu Chen (Danilo Montes) and the eponymous bandit king--two men who meet as mistrustful antagonists and part as brothers in blood.

Wong believes he's done Liu Chen a favor by rescuing him from the clutches of a greedy general (Gil De Leon, husband of Ms. Dizon and father of Christopher) out to learn the location of Chen's treasure, but the man is more goading than grateful--the general had raped and driven to suicide Chen's freshly wedded wife (Lola Young), and he wants Wong's help in exacting revenge. Like a troublesome conscience Chen reminds Wong of promises unfulfilled, of deeds left undone, and suggests (without saying so directly) that Wong can be a better man than he thinks he is, that as is he's a heavy-breathing braggart and something of a coward (not that Chen is a paragon of virtue--played by Montes, he's a self-righteous prig and hothead).

De Leon sketches the blackly comic relationship between his two protagonists, two men who couldn't be more different (and couldn't be more conscious of that fact), yet are inextricably entwined; a pulpy romp like Raiders of the Lost Ark, by way of comparison, is a mere cartoon, a fairly well-directed one; you thrill to Jones' exploits, but never feel that Jones has struggled with anything deeper than an archeological dig, or suffered the loss of anything more significant than his floppy hat.

There are flaws--an outrageous one being the scene where Wong, in an extravagant fit of cruelty, strips the Amazon down to her leopardskin (Leopardskin! In China!) and forces her to dance a vaguely African dance choreography. This is a cheesecake scene, of course, designed to show off Ms. Dizon's superb figure (Dizon, incidentally, is sexier and far more sensuous in leopardskin than most Filipina softcore porn stars are in their birthday suits nowadays--one hundred percent natural equipment mind you, no plastic surgery involved).

But to point out historical and cultural errors is to miss the point of B movies (so called because they were (supposedly) a notch below the class-A pictures); it's denying the wild and anything-goes spirit in which these movies were made--and in fact, there is a psychological rationale behind this scene: some shameful act is eating Wong up inside, and he has to lash out at the nearest available scapegoat, in this case his favorite woman. Sadomasochism in a '50s Filipino-Hong Kong co-production? Absolutely.

I love the python, under the control of a magic ring; the python's scenes are entirely believable (this plus the crocodile attack in Noli Me Tangere suggests De Leon had a way with untamed creatures), with every appearance timed to cause the maximum number of gasps. Compare this to the snake scene in the recent magic-realist Sa Pusod Ng Dagat (In the Navel of the Sea): that sorry little reptile simply popped out of the woman's vagina--no attempt was made to prepare you for this unlikely miracle, no attempt made to do anything more with it. In effect the snake in Pusod was a huge bore, the snake in Sanda a small delight.

Sanda Wong is a mix of skillful storytelling, superbly staged action, and sumptuous production design--everything effortlessly balanced against each other, lightly held in the palm of De Leon's masterful hand. Not a great film, but definitely great entertainment.

First published in Businessworld, 3.6.98.

Article reprinted in Critic After Dark: A Review of Philippine Cinema, available online

Wednesday, October 02, 2013

Maynila sa mga kuko ng liwanag (Manila in the Claws of Neon, Lino Brocka, 1975)

To be released by the Criterion Collection on June 12, 2018, Lino Brocka's best-known film.

Some thoughts (pre-restoration) on the film:

Some thoughts (pre-restoration) on the film:

Maynila at the edge of greatness

(Warning: plot discussed in close detail)

Lino Brocka is the best Filipino filmmaker ever; his masterpiece, Maynila sa mga Kuko ng Liwanag (Manila in the Claws of Neon, 1975) the greatest Filipino film ever made.

That was the consensus arrived at sometime after Maynila first came out, and the idea has persisted ever since. Has, in fact, been given greater legitimacy with a top spot in the Urian's list of the ten best Filipino films in the past thrty years, and by inclusion in the book Film: the Critic's Choices--a list of what some critics consider the 150 greatest films ever made.

That's what they say. What about us--you, me, the mere mortals? What do we think?

Norte, the End of History (Lav Diaz, 2013) screened at the New York Film Festival!

Would have been nice to know about it beforehand--but nice to know it was screened there, nevertheless.

My Film Comment article on in my book the best film of the year

Excerpt:

In Norte: Hangganan ng Kasaysayan (Norte: the End of History) Fabian (Sid Lucero) is our brilliant yet alienated Raskolnikov; Magda (wonderful Mae Paner) the massively avaricious pawnbroker Mrs. Ivanovna. Archie Alemania plays Joaquin, and we're not sure who is his equivalent in the novel, only that he's another of Magda's client, as desperate if not more so than Fabian (he and his wife were about to open a small diner when an accident cripples him and sucks up his startup capital).

The first half feels like a direct transposition to a Philippine setting: Fabian is a topnotch law student who has dropped out for vague reasons, which hasn't stopped him from eloquently, endlessly debating with friends and former law professors. Like Raskolnikov Fabian believes in a sentiment-hating, results-oriented, vaguely Nietzschean philosophy; like Raskolnikov Fabian longs to put his philosophy into practice in the most radical way possible: by killing an utterly irredeemable (in his mind anyway) human being, the fat and heartless Magda, and stealing her money. The deed done the film takes a quietly radical turn: instead of a relentless manhunt, a false accusation; instead of Raskolnikov's desperate evasion of the authorities Fabian embarks on an existential and at one point self-destructive quest.