The Quiet Man passes

Mario Herrero O'Hara was known, if he was known at all, as legendary filmmaker Lino Brocka's collaborator; more malicious wags called him Brocka's lover (for the record--no, and there's a reason why).

He acted in several of Brocka's early films playing a vivid villain in Tubog sa Ginto (Dipped in Gold, 1971) a neglected son in Stardoom (1971) opposite actress Lolita Rodriguez; three years later he played Rodriguez's leprous lover in Brocka's seminal film Tinimbang Ka Ngunit Kulang (You Were Weighed But Found Wanting) having also written the film's screenplay.

O'Hara wrote the teleplay that was the basis for what is arguably Brocka's best work Insiang (1976); it went on to be the first-ever Filipino film to be screened in the Director's Fortnight in Cannes. The film--about a slum girl raped by her mother's lover--is often called a masterpiece of realism and no wonder; O'Hara claimed in an interview that the story happened to his backyard neighbors in the city of Pasay.

(It's also claimed--and here you see the state of Filipino film history, that many details are open to contention or can rarely be definitively documented--that the teleplay was based on a radio script written by actress and scriptwriter Mely Tagasa. Quite possibly both stories are true: O'Hara took the premise from Ms. Tagasa's radio script but based details of the characters on his neighbors...)

It was ever so in O'Hara's films and screenplays, his insistence that everything and anything in his works be true no matter how fantastic. An outre character (a faded movie actress living in a cemetery crypt) an outrageous occurrence (a historical figure falling in love with his literary creation) can be allowed in his films only if they were by some convoluted definition true.

O'Hara was notorious for not using a motorized vehicle--or rather he owned a van but drove it only on weekends and film shoots (he had a chauffeur who drove him around that he would also parsimoniously use in bit parts--once spotted the old man playing Jose Rizal's father). Weekdays he took public utility jeeps and buses and walked for hours from his house in Bangkal Makati to Divisoria in Manila (a distance of some five miles), these marathon walks often being a source of his stories characters bits of dialogue incidents (a particularly torrid film scene involving lovers coupling in a tricycle was inspired he once claimed by something he actually saw happen on Taft Avenue). The joke was that you had to watch yourself when talking to the man--he was liable to put you in a movie someday sometimes without your permission.

O'Hara would make his directorial debut with Mortal (1975) his fabulist re-telling of a real-life murder committed by a paranoid schizophrenic; the film was to be one of the first produced by the just-established Cine Manila under which Brocka had hoped to produce films. The murder victim's family sued and won unfortunately and Cine Manila quickly folded.

O'Hara's second film was to be his first with popular singer-actress Nora Aunor. Aunor had been looking for a prestige project to produce and star in and asked for Brocka; Brocka didn't want to have “anything to do with that Superstar!” and passed the project to O'Hara. O'Hara dug up an old script and on a budget of about a million pesos--modest for a World War 2 drama of that scale and ambition--created Tatlong Taong Walang Diyos (Three Years Without God 1976) about the three years of Japanese Occupation when as the title suggests God turned his face away from the Filipino people. The film is possibly the actress-producer's best performance arguably the director's finest feature and--possibly arguably strictly-my-opinion--the finest Filipino film ever made.

First

Act

Mario O'Hara was born in Zamboanga City on April 20 1946, the son of half Irish-American half Filipino lawyer Jaime O'Hara from Antipolo Rizal and Basilisa Herrero from Ozamis Oriental. Jaime O'Hara's father was a Thomasite teacher one of the earliest sent to the Philippines, and this fact alone allowed the O'Haras including Mario the chance to immigrate to the United States (Mario turned the offer down).

It was a large family--eight brothers and three sisters--and according to O'Hara a happy one, with a childhood fueled by the imaginative power of night-time radio. His neighborhood--some time after his birth the family had moved to Pasay City--had rich mansions on either side and a slum directly behind; O'Hara said many of his TV scripts came out of that backyard slum. One of his brother's friends owned a movie theater and they watched films for free--the titles included Michael Curtiz's The Adventures of Robin Hood and the Flash Gordon serials.

O'Hara planned a practical career--a chemical engineering degree earned at Adamson University--but the call of that childhood voice proved too strong. On his sophomore year he auditioned for a part in a Proctor and Gamble radio show at the Manila Broadcasting Corporation; by third year college he dropped out because he couldn't handle the load of both studying and performing on radio.

Mario O'Hara was born in Zamboanga City on April 20 1946, the son of half Irish-American half Filipino lawyer Jaime O'Hara from Antipolo Rizal and Basilisa Herrero from Ozamis Oriental. Jaime O'Hara's father was a Thomasite teacher one of the earliest sent to the Philippines, and this fact alone allowed the O'Haras including Mario the chance to immigrate to the United States (Mario turned the offer down).

It was a large family--eight brothers and three sisters--and according to O'Hara a happy one, with a childhood fueled by the imaginative power of night-time radio. His neighborhood--some time after his birth the family had moved to Pasay City--had rich mansions on either side and a slum directly behind; O'Hara said many of his TV scripts came out of that backyard slum. One of his brother's friends owned a movie theater and they watched films for free--the titles included Michael Curtiz's The Adventures of Robin Hood and the Flash Gordon serials.

O'Hara planned a practical career--a chemical engineering degree earned at Adamson University--but the call of that childhood voice proved too strong. On his sophomore year he auditioned for a part in a Proctor and Gamble radio show at the Manila Broadcasting Corporation; by third year college he dropped out because he couldn't handle the load of both studying and performing on radio.

In 1968 O'Hara met Lino Brocka; Brocka in turn used him as an actor on the big screen and on the theater stage doing productions for PETA (Philippine Experimental Theater Association). O'Hara came to helm his first feature by criticizing Brocka's style of film direction. “If you know so much, why don't you direct?” Brocka finally said. Brocka wanted to do an adaptation of Edgardo Reyes' serialized novel Sa Mga Kuko ng Liwanag (In the Claws of Light), to be produced by Mike de Leon, so he gave the film Mortal (which he had been slated to direct) to O'Hara.

The career high of Tatlong Taong Walang Diyos was followed by the career low of Mga Bilanggong Birhen (The Captive Virgins, 1977), yet another period epic. O'Hara was fired after accomplishing ninety-five percent of principal photography (“I couldn't see eye-to-eye with the producer,” he said); the picture was finished by another director.

We would see this tendency time and time again--a film where O'Hara either abandoned the project or allowing himself to be fired. On set he's described as a diligent determined worker but the moment you interfere he was likely to drop matters and simply walk away.

One might try explain this tendency through O'Hara's attitude towards filmmaking once articulated thusly: "first an actor, second a writer, and lastly a director." The self-confessed lack of commitment to cinema (think of Orson Welles spending four years of his life to finish Othello) can on one hand be considered a fatal flaw in that O'Hara was often more opportunist than self-starter, his finished features far fewer than they could have been.

On the other hand this gave his work an independent quality a fearlessness with regards to fellow filmmakers' (and movie audiences') uncomprehending possibly angry responses to his more eccentric films (in Mortal for example the film proceeds in a fragmentary hallucinatory manner, only later becoming more coherent--the way the protagonist's schizophrenic mind becomes clearer as his mind grows gradually saner).

Mga Bilanggong Birhen helped established a pattern: when O'Hara couldn't direct a film he directed for television; when he couldn't direct at all he acted; when he wasn't acting he wrote. He performed for theater radio television film; he wrote scripts for Brocka and once for filmmaker Laurice Guillen's debut feature (Kasal? 1980); he also directed the television soap Flordeluna for a year.

O'Hara

wrote Ang Palayso ni Valentin

(The

Palace of Valentin)

a zarzuela

(a form of Filipino musical theater) about a decaying theater's

decaying pianist and his undying love for the theater's beautiful

singing star. The play was O'Hara's valentine to the theatrical arts

and won the 1998 Centennial Literary Competition grand prize for

drama. In 2002 he reworked his best-known collaboration with Brocka

(Insiang)

into a stage play

with the action relocated back in Pasay City where he had originally

set it (Brocka's film was set in Tondo), adding a hip and funny

narrator (much like The Common Man in Robert Bolt's A

Man For All Seasons)

to comment on and provide context to the drama.

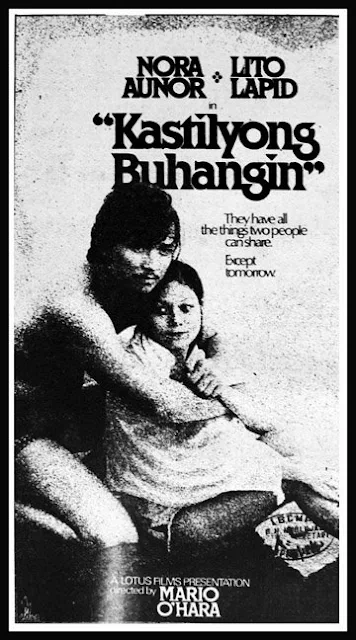

In the '80s, O'Hara would hit his stride on the big screen. His Kastilyong Buhangin (Castle of Sand 1980) was a vehicle for both Aunor's singing talents and stuntman-turned-actor Lito Lapid physical prowess a bizarre yet spirited union between George Cukor's A Star is Born and Ringo Lam's Prison on Fire. His Bakit Bughaw ang Langit? (Why is the Sky Blue? 1981) about a shy young woman (Aunor again) who falls in love with a mentally incapacitated young man is O'Hara directly challenging mentor and friend Brocka on Brocka's own social-realist territory. And then there was what might arguably be called O'Hara's Manila noir trilogy: Condemned (1984), about a brother and sister (Aunor again) on the run in the streets of Malate from a dollar-smuggling gang; Bulaklak sa City Jail (Flowers of the City Jail, 1984) about a pregnant woman (Aunor yet again) incarcerated in the city's hellish prison system; and Bagong Hari (The New King 1986) about a man hired to unwittingly assassinate his own father. The three films present a grim portrait of tManila (the last earning an “X” rating from the censors for extreme violence), and might arguably be called the zenith of Filipino noir.

Pygmalion

If a good proportion of O'Hara's films seemed to feature Aunor there was likely a reason. O'Hara was one of the first filmmakers to recognize her worth as an actress back when she was considered a 'mere' multimedia pop star; both were shy private people who only when required to do so (in public speaking or before a camera) switch on the thousand-watt bulb of their charisma. This seeming timidity concealing formidable talent is possibly the basis for the rapport between them, a spiritual resonance rarely found in other actress-director collaborations in Philippine cinema; you might even call Aunor the filmmaker's doppelganger his onscreen expression of inner strength and hidden vulnerability, to be sorely tried and tested by the tortuous narratives of his films. For whatever reason, the titles (Tatlong Taong Walang Diyos, Bakit Bughaw ang Langit? among many others) speak for themselves: O'Hara's work with Aunor represent some of the best that either artist or Philippine cinema itself has to offer.

Pito-pito Films

In 1998 head of Regal Films “Mother” Lily Monteverde with the help of filmmaker/producer Joey Gosiengfiao established Good Harvest, a subdivision of Regal designed to churn out pito-pito pictures, the term (which translates literally into “seven-seven”) referring to the speed with which the films are to be made (seven days of shooting, seven of post-production). The basic premise: the filmmakers are given seed money (two and a half million pesos, or roughly $62,500) an insanely tight production schedule (seven days filming, seven post-production) with the only stipulation being that the films should have commercial appeal (sex violence); otherwise the filmmakers have carte blanche approval to do whatever they want.

The pito-pito system helped newcomers produce their debut features helped veterans realize dream projects; O'Hara shot not one but two pictures in fourteen days. Babae sa Bubungang Lata (Woman on a Tin Roof, 1998) his adaptation of Agapito Joaquin's two-character one-act chamber drama expanded into a eulogy for the Filipino film industry and Sisa his tribute to Filipino historical figure and hero Jose Rizal, turning on the conceit that Rizal did not fashion his most famous literary creation out of whole cloth but actually knew her, as a living breathing red-blooded woman and the love of his life (Shakespeare in Love with a fraction of the production budget and an insanely imaginative approach).

Final

Act

In 2000 O'Hara directed his final pito-pito film: Pangarap ng Puso (Demons) about a pair of children who live near the Negros' enchanted rain forests fall in love are pulled into the tumultuous currents of history. Their development is reflected in their evolving view of the creatures dancing about them--as a child's metaphor for the wide unknown world; as a pubescent's metaphor for emerging sexuality; as a young adult's metaphor for the impulses that drive terrorists and military fascists alike, locked in a never ending cycle of violence and revenge.

And it's so much more; the girl's mother (Hilda Koronel) recites Florentino Collantes' "The Gift," part of which I translated (very roughly):

Our love is like the heaven and earth

the union of mountain and sea.

Too close to be seen apart

drinking bitter tears.

I remember my lifelong love

how he lay ailing

how I said that if he ever died

I would quick follow

In 2000 O'Hara directed his final pito-pito film: Pangarap ng Puso (Demons) about a pair of children who live near the Negros' enchanted rain forests fall in love are pulled into the tumultuous currents of history. Their development is reflected in their evolving view of the creatures dancing about them--as a child's metaphor for the wide unknown world; as a pubescent's metaphor for emerging sexuality; as a young adult's metaphor for the impulses that drive terrorists and military fascists alike, locked in a never ending cycle of violence and revenge.

And it's so much more; the girl's mother (Hilda Koronel) recites Florentino Collantes' "The Gift," part of which I translated (very roughly):

Our love is like the heaven and earth

the union of mountain and sea.

Too close to be seen apart

drinking bitter tears.

I remember my lifelong love

how he lay ailing

how I said that if he ever died

I would quick follow

The

daughter would inherit this love of poetry. But times being as

troubled as they are she is drawn to darker more unsettling fare,

such as Amado Hernandez's piece about political prisoners (again very

roughly translated):

Bright

as lightning the guardian’s eye

on this locked and forbidding gate;

the convict in the next cell howls

an animal trapped in a cave.

Each day passes like a chain dragged

along the floor by bloody feet

on this locked and forbidding gate;

the convict in the next cell howls

an animal trapped in a cave.

Each day passes like a chain dragged

along the floor by bloody feet

each

night is a mourning shroud draped

on

my place of entombment.

Sometimes someone's furtive feet pass,

clink of shackles marking passage;

the sallow sun blinks, reveals

countless wraiths spewing from the dark.

Sometimes the night's peace is shattered

by alarm--an escape!--gunfire;

sometimes the old church bell tolls

and in the courtyard someone dies--

The girl grows up, faces her demons, conquers them (but not entirely as we shall see in the film); she becomes involved in the region's violent politics though not as deeply as her childhood sweetheart, who has a bounty worth thousands of pesos on his head. Her speeches are admirably progressive but--in what I find to be a curious reaction to the young man's rebellion--her poetry is more personal than radical (these lines written not by a famous Filipino poet, but by O'Hara's niece; again a rough and probably incompetent translation):

At the graveside of childhood

in this tract of red-stained fetid soil

the dying is done.

The final breath was deep

filled with purpose

because the heavens do not mourn a man

and begrudge tears to a garden reserved

for standing, stagnating saints.

Orphans begging by the tombstones of cemeteries.

But the dead understand.

Beneath their burial and putrefaction

is mourning and begging.

Remarkable

coming from a young woman--but not her best; her best verses are

recited at the end of the film and they are heartbreaking: the story

of two lives captured in a handful of words.

I was asked once after a screening of this film (by the late Nika Bohinc if I remember rightly): why would children be frightened of the spirits of the forest when all they have known is innocence and joy? I had an answer then a fairly good one I thought but having mulled things over feel this is how I should have answered: that what children know is so very little compared to what they can see going on about them, that even with their handful of knowledge (or rather because of it--what was Socrates' definition of a truly wise man?) they can sense danger and darkness beyond their small safe circle. Children can sense and see and in this way know (even if they are not sure of the particulars); thus equipped and not incapable of imagination they can fear. When they grow up into flawed adults (a budding poetess and crusader, a feared rebel killer) their knowledge increases and their circle's width widens; but the darkness is never fully dispelled and the fear never goes completely away.

In 2003 O'Hara did Babae sa Breakwater (Woman of the Breakwater) about the homeless folk who live along Manila's breakwater--again O'Hara straying into Brocka territory (most notably Maynila sa Mga Kuko ng Liwanag) only with a strong strain of magic realism running throughout, troubadour Yoyoy Villiame commenting on the onscreen action through song (again, Robert Bolt's The Common Man but set to music). His Ang Paglilitis ni Andres Bonifacio (The Trial of Andres Bonifacio 2010) uses the actual minutes of the trial of Supremo Andres Bonifacio (much as Carl Theodor Dreyer did in The Passion of Joan of Arc) as basis and occasion to give this long-neglected contemporary of Rizal the low-budget magic-realist due he deserves.

O'Hara's reunion with his oft-muse Nora Aunor would prove to be his last major work. Sa Ngalan ng Ina (In the Name of the Mother 2011) a mini-series retelling recent Filipino politics in teleserye format, turns on the conceit that much of the melodramatic excesses of contemporary Filipino soap opera (the drama the betrayals the sex and violence) reflect the melodramatic excesses of contemporary Filipino politics (the drama the betrayals the sex and violence). By this time O'Hara's health may not have been what it used to be; he codirected this tremendous effort (twenty-five hour-long episodes) with Jon Red, who also did all the series' action sequences.

I was asked once after a screening of this film (by the late Nika Bohinc if I remember rightly): why would children be frightened of the spirits of the forest when all they have known is innocence and joy? I had an answer then a fairly good one I thought but having mulled things over feel this is how I should have answered: that what children know is so very little compared to what they can see going on about them, that even with their handful of knowledge (or rather because of it--what was Socrates' definition of a truly wise man?) they can sense danger and darkness beyond their small safe circle. Children can sense and see and in this way know (even if they are not sure of the particulars); thus equipped and not incapable of imagination they can fear. When they grow up into flawed adults (a budding poetess and crusader, a feared rebel killer) their knowledge increases and their circle's width widens; but the darkness is never fully dispelled and the fear never goes completely away.

In 2003 O'Hara did Babae sa Breakwater (Woman of the Breakwater) about the homeless folk who live along Manila's breakwater--again O'Hara straying into Brocka territory (most notably Maynila sa Mga Kuko ng Liwanag) only with a strong strain of magic realism running throughout, troubadour Yoyoy Villiame commenting on the onscreen action through song (again, Robert Bolt's The Common Man but set to music). His Ang Paglilitis ni Andres Bonifacio (The Trial of Andres Bonifacio 2010) uses the actual minutes of the trial of Supremo Andres Bonifacio (much as Carl Theodor Dreyer did in The Passion of Joan of Arc) as basis and occasion to give this long-neglected contemporary of Rizal the low-budget magic-realist due he deserves.

O'Hara's reunion with his oft-muse Nora Aunor would prove to be his last major work. Sa Ngalan ng Ina (In the Name of the Mother 2011) a mini-series retelling recent Filipino politics in teleserye format, turns on the conceit that much of the melodramatic excesses of contemporary Filipino soap opera (the drama the betrayals the sex and violence) reflect the melodramatic excesses of contemporary Filipino politics (the drama the betrayals the sex and violence). By this time O'Hara's health may not have been what it used to be; he codirected this tremendous effort (twenty-five hour-long episodes) with Jon Red, who also did all the series' action sequences.

All

that passion all those sleepless nights the massive strain on

O'Hara's health (at one point shooting Babae

sa Bubungang Lata

and Sisa

back-to-back) must have come at a cost. On June 19, 2012 the report

came out over online social media that O'Hara had been rushed to the

emergency room due to symptoms of acute leukemia; the family,

respectful of his retiring nature, withheld the hospital's name (it

was later revealed to be San Juan de Dios). Brother Jerry O'Hara

reported that he responded well to chemotherapy. The optimism was

premature: on the morning of June 26 word went out that O'Hara had

succumbed to cardiac arrest, the quiet man silenced at last.

Curtain

Call

O'Hara's significance to Philippine cinema is a challenge to assess. Unlike his more outspoken contemporaries Lino Brocka and Ishmael Bernal, O'Hara disliked discussing the ideas behind his films; he much preferred to stay in the background playing cup-bearer to the industry's gaudier princes.

There's an additional difficulty: if the works of older generation Filipino filmmakers are generally not readily available (Brocka's Tubog sa Ginto for example exists only as bootleg video) O'Hara's are even more troublesome to obtain. I'd say at least four or five of the twenty-five features he directed have no existing print, and that only six are readily available on DVD--not the clearest of copies and without subtitles (unless otherwise indicated). His masterpiece Tatlong Taong Walang Diyos is on Youtube with subtitles though I refuse to link to that travesty; the experience is like viewing Velasquez's Las Meninas from the bottom of a septic tank (not a big fan of the translation either). In trying to talk about his films you can't help but think of the seven blind men trying to describe an elephant; impossible to do justice to the wondrous creature.

Nevertheless--

O'Hara was a crucial collaborator of Brocka's, and it's possible to argue that he introduced a note of moral ambiguity not found in Brocka's other pictures--at the end of Insiang for example one couldn't really tell who was the victim who the victimizer; in Tinimbang Ka Ngunit Kulang it's suggested that O'Hara character (Berto the Leper) is a possible rapist. He took up Brocka's social-realist mode of storytelling (Bakit Bughaw ang Langit?) and introduced baroque even fabulist variations (Mortal, The Fatima Buen Story (1994)); later in his career he managed to fashion a mode of cinema inimitably his--imaginative in both form and content yet filled with political sociological historical concerns (Pangarap ng Puso, Sisa).

Arguably O'Hara was more fluent than Brocka in the language of action filmmaking. The prison riot that climaxes Kastilyong Buhangin, the varied and at times elaborate fight sequences throughout Bagong Hari--his precise editing use of pointedly angled shots distinctly staged mis-en-scene reveal a visual descendant of Gerardo de Leon (and behind de Leon classic filmmakers like Ford, Eisenstein, Griffith).

O'Hara's early training in radio possibly distinguished him from other Filipino filmmakers of the '70s, who mostly came from theater: I submit that this training helped free him (the way it freed another filmmaker active in radio, stage and film) from the tyranny of the proscenium arch, giving one the sense of watching a film film instead of a film recording of a stage performance. Musical cuing (Brocka's weakness according to O'Hara), sound transitions, overlapping dialogue linked his images subtly amplified their cumulative emotional power. More, there was a fluidity to his editing (see Pangarap ng Puso, where the montage of photo stills act like the flicker-images of memory), a constant bounding from reality to fantasy and back (the protagonist's schizophrenia in Mortal, the supernatural creatures surrounding the children in Pangarap ng Puso) that suggests not so much a spatial orientation as an aural one, or at least one less limited by the unities of a specific location--a heedless leaping across time and space and emotion, taught to him by the equally fearless transitions (from present to past, reality to fantasy, comedy to drama) found in the radio shows of his early career.

O'Hara's significance to Philippine cinema is a challenge to assess. Unlike his more outspoken contemporaries Lino Brocka and Ishmael Bernal, O'Hara disliked discussing the ideas behind his films; he much preferred to stay in the background playing cup-bearer to the industry's gaudier princes.

There's an additional difficulty: if the works of older generation Filipino filmmakers are generally not readily available (Brocka's Tubog sa Ginto for example exists only as bootleg video) O'Hara's are even more troublesome to obtain. I'd say at least four or five of the twenty-five features he directed have no existing print, and that only six are readily available on DVD--not the clearest of copies and without subtitles (unless otherwise indicated). His masterpiece Tatlong Taong Walang Diyos is on Youtube with subtitles though I refuse to link to that travesty; the experience is like viewing Velasquez's Las Meninas from the bottom of a septic tank (not a big fan of the translation either). In trying to talk about his films you can't help but think of the seven blind men trying to describe an elephant; impossible to do justice to the wondrous creature.

Nevertheless--

O'Hara was a crucial collaborator of Brocka's, and it's possible to argue that he introduced a note of moral ambiguity not found in Brocka's other pictures--at the end of Insiang for example one couldn't really tell who was the victim who the victimizer; in Tinimbang Ka Ngunit Kulang it's suggested that O'Hara character (Berto the Leper) is a possible rapist. He took up Brocka's social-realist mode of storytelling (Bakit Bughaw ang Langit?) and introduced baroque even fabulist variations (Mortal, The Fatima Buen Story (1994)); later in his career he managed to fashion a mode of cinema inimitably his--imaginative in both form and content yet filled with political sociological historical concerns (Pangarap ng Puso, Sisa).

Arguably O'Hara was more fluent than Brocka in the language of action filmmaking. The prison riot that climaxes Kastilyong Buhangin, the varied and at times elaborate fight sequences throughout Bagong Hari--his precise editing use of pointedly angled shots distinctly staged mis-en-scene reveal a visual descendant of Gerardo de Leon (and behind de Leon classic filmmakers like Ford, Eisenstein, Griffith).

O'Hara's early training in radio possibly distinguished him from other Filipino filmmakers of the '70s, who mostly came from theater: I submit that this training helped free him (the way it freed another filmmaker active in radio, stage and film) from the tyranny of the proscenium arch, giving one the sense of watching a film film instead of a film recording of a stage performance. Musical cuing (Brocka's weakness according to O'Hara), sound transitions, overlapping dialogue linked his images subtly amplified their cumulative emotional power. More, there was a fluidity to his editing (see Pangarap ng Puso, where the montage of photo stills act like the flicker-images of memory), a constant bounding from reality to fantasy and back (the protagonist's schizophrenia in Mortal, the supernatural creatures surrounding the children in Pangarap ng Puso) that suggests not so much a spatial orientation as an aural one, or at least one less limited by the unities of a specific location--a heedless leaping across time and space and emotion, taught to him by the equally fearless transitions (from present to past, reality to fantasy, comedy to drama) found in the radio shows of his early career.

Not

that he turned his back completely on theatricality. In Bubungang

Lata

he would present large swathes of Joaquin's play as

a play, two characters moving about in a tiny set with the camera

just sitting there drinking in their performances; the plainness of

the approach underlined the plainness of their lives their

aspirations (this in contrast to the film's more fabulist characters,

who are shot in a variety of angles and lighting). In Ang

Paglilitis ni Andres Bonifacio

(his first digital feature) O'Hara refrains from taking advantage of

digital video's most obvious virtues (easy handheld shots) and

instead locks down the camera, viewing the actors with an unblinking

dispassionate eye (if anything he takes advantage of digital's other

virtue, uninterrupted long takes). The stable framing and vivid color

palette emphasizes a stylization not inappropriate to a moro-moro

(yet another specifically Filipino form of theater) production, one

of which is quoted extensively onscreen, and serves as unspoken

commentary on the politics behind the trial (in the moro-moro

the outcome is settled long before the play begins).

The

heart of the matter

O'Hara's cinematic virtuosity would mean little without a moral and philosophical stance--this being possibly the most difficult aspect to pin down. His personal reticence his reluctance to clarify and explicate his thoughts and intentions in real life extends to his films; in his very best work it's near impossible (Who is the victim? Who the victimizer?). O'Hara's films like those of friend and mentor Brocka depict extremes of love lust hate contempt sadism tenderness; unlike Brocka you sense a consistent distance between O'Hara and his subjects. The immediacy the urgency the white-hot anger that pulses through Brocka's films is missing in O'Hara's, the same time there are a few emotional hues in O'Hara that are missing in Brocka (cynicism (the finale of Condemned); sardonic humor (the severed head in Bagong Hari)). The title of Brocka's breakthrough film summarizes his attitude towards his characters: he judges them constantly and thoroughly, with little ambivalence.

O'Hara doesn't; there's a yawning cavern of silence where his attitude towards characters should be. He doesn't seem to hate his villains (the Japanese rapist in Tatlong Taong Walang Diyos) doesn't seem to particularly love his heroes (the hapless stuntman in Babae sa Bubungang Lata). His camera has that unblinking quality found in more contemplative Filipino filmmakers (Mike de Leon, Ishmael Bernal, Lav Diaz to name a few). On occasion you find him cutting to a high-angle shot--the point of view of a scientist or deity gazing down on its test subject or worshippers.

But if you look and listen closely--again that aural element--pay close attention to his framing, timing of cuts, choices in staging and line readings there is the whisper hint suggestion of an attitude. The blind man carrying his palsied brother past the religious procession in Tatlong Taong Walang Diyos; Babette saying goodbye in Bakit Bughaw ang Langit?--the first sequence wordless (the swaying edifice the pair of shuffling figures) the second nothing but words (Aunor's delicately shaded delivery suggesting Babette's state of mind). O'Hara keeps the lamp-flame indicating his scenes' emotional temperature burning low low low until you realize what the scene is really about and the full meaning explodes. Where Brocka was a revolutionary raising a fist demanding change at the barricades O'Hara was a subversive smuggling explosives past said barricades.

O'Hara's distance is no assumed pose; he's far too clear-eyed about the perversity of human nature to think we're just misunderstanding each other or instinctively inflicting our own inner pain on each other. He understands that there is keen pleasure to be found in imposing pain (again the Japanese rapist in Tatlong Taong Walang Diyos) that there are those among us who crave that pleasure in regular doses (the police officer in Babae sa Breakwater, Rex in Bagong Hari). You hear a whisper from the cavern's mouth; when O'Hara's films are working full-on you feel the hairs on the back of your neck rise as you sense--the way a sensitive senses the supernatural--that O'Hara does care about his characters cares for them deeply but is too much of an artist to let his concern speak too loudly. Understanding this contradictory pull between the impassive and empathic in O'Hara, this double-vision if you will, is key to understanding his cinema.

What to say finally of O'Hara the filmmaker? I could write for years and it wouldn't be enough but a few words might help: he is I believe Philippine cinema's wayward spirit, its silent wanderer-observer (especially around the Makati-Malate-Quiapo-Divisoria area) its whispered yet insistent conscience. He is its reluctant poet its low-key fabulist its (to borrow a phrase from Manny Farber) termite artist, toiling away in mud and filth to build something that isn't intended to be anything beautiful, perhaps doesn't even presume to become anything near beautiful, but which somehow in some way almost by accident if you will (though this random quality may be a mark of its authenticity) achieves a wayward reluctant beauty.

He is (again strictly in my opinion) the Philippine's finest filmmaker; his death does our cinema an irretrievable irrecoverable harm--not just for the life's worth of recognition owed to him but for the works he might have given us if he lived but a year longer (I once spent an evening listening to him talk of the scripts he has squirreled away, one more fabulous than the next). The world is a quieter place with this man gone, not necessarily a better one. We do well to mourn our loss.

First published in Businessworld, 6.28.12

O'Hara's cinematic virtuosity would mean little without a moral and philosophical stance--this being possibly the most difficult aspect to pin down. His personal reticence his reluctance to clarify and explicate his thoughts and intentions in real life extends to his films; in his very best work it's near impossible (Who is the victim? Who the victimizer?). O'Hara's films like those of friend and mentor Brocka depict extremes of love lust hate contempt sadism tenderness; unlike Brocka you sense a consistent distance between O'Hara and his subjects. The immediacy the urgency the white-hot anger that pulses through Brocka's films is missing in O'Hara's, the same time there are a few emotional hues in O'Hara that are missing in Brocka (cynicism (the finale of Condemned); sardonic humor (the severed head in Bagong Hari)). The title of Brocka's breakthrough film summarizes his attitude towards his characters: he judges them constantly and thoroughly, with little ambivalence.

O'Hara doesn't; there's a yawning cavern of silence where his attitude towards characters should be. He doesn't seem to hate his villains (the Japanese rapist in Tatlong Taong Walang Diyos) doesn't seem to particularly love his heroes (the hapless stuntman in Babae sa Bubungang Lata). His camera has that unblinking quality found in more contemplative Filipino filmmakers (Mike de Leon, Ishmael Bernal, Lav Diaz to name a few). On occasion you find him cutting to a high-angle shot--the point of view of a scientist or deity gazing down on its test subject or worshippers.

But if you look and listen closely--again that aural element--pay close attention to his framing, timing of cuts, choices in staging and line readings there is the whisper hint suggestion of an attitude. The blind man carrying his palsied brother past the religious procession in Tatlong Taong Walang Diyos; Babette saying goodbye in Bakit Bughaw ang Langit?--the first sequence wordless (the swaying edifice the pair of shuffling figures) the second nothing but words (Aunor's delicately shaded delivery suggesting Babette's state of mind). O'Hara keeps the lamp-flame indicating his scenes' emotional temperature burning low low low until you realize what the scene is really about and the full meaning explodes. Where Brocka was a revolutionary raising a fist demanding change at the barricades O'Hara was a subversive smuggling explosives past said barricades.

O'Hara's distance is no assumed pose; he's far too clear-eyed about the perversity of human nature to think we're just misunderstanding each other or instinctively inflicting our own inner pain on each other. He understands that there is keen pleasure to be found in imposing pain (again the Japanese rapist in Tatlong Taong Walang Diyos) that there are those among us who crave that pleasure in regular doses (the police officer in Babae sa Breakwater, Rex in Bagong Hari). You hear a whisper from the cavern's mouth; when O'Hara's films are working full-on you feel the hairs on the back of your neck rise as you sense--the way a sensitive senses the supernatural--that O'Hara does care about his characters cares for them deeply but is too much of an artist to let his concern speak too loudly. Understanding this contradictory pull between the impassive and empathic in O'Hara, this double-vision if you will, is key to understanding his cinema.

What to say finally of O'Hara the filmmaker? I could write for years and it wouldn't be enough but a few words might help: he is I believe Philippine cinema's wayward spirit, its silent wanderer-observer (especially around the Makati-Malate-Quiapo-Divisoria area) its whispered yet insistent conscience. He is its reluctant poet its low-key fabulist its (to borrow a phrase from Manny Farber) termite artist, toiling away in mud and filth to build something that isn't intended to be anything beautiful, perhaps doesn't even presume to become anything near beautiful, but which somehow in some way almost by accident if you will (though this random quality may be a mark of its authenticity) achieves a wayward reluctant beauty.

He is (again strictly in my opinion) the Philippine's finest filmmaker; his death does our cinema an irretrievable irrecoverable harm--not just for the life's worth of recognition owed to him but for the works he might have given us if he lived but a year longer (I once spent an evening listening to him talk of the scripts he has squirreled away, one more fabulous than the next). The world is a quieter place with this man gone, not necessarily a better one. We do well to mourn our loss.

First published in Businessworld, 6.28.12

6 comments:

noel, the tribute was from cinema one originals.

My bad. Corrected.

Thank you. This all needed to be said. I do hope a book comes soon. And if someone could please find his films!

Your lips to God's ear.

what a great tribute! thanks. i've been an o'hara fan without knowing (i mean without being aware that he was the author behind such impressive works)

Thanks. Which ones have you seen?

Post a Comment